Scientists tout potential ‘clean’ replacement for fossil fuels as companies develop new projects.

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found at https://www.ft.com/tour. https://www.ft.com/content/959d08e2-a899-11e9-984c-fac8325aaa04 A Toyota worker loads hydrogen tanks on a production line. For energy majors, hydrogen, which can be produced from fossil fuels, could offer a way of securing a function for their natural gas reserves © Reuters

Please use the sharing tools found via the share button at the top or side of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found at https://www.ft.com/tour. https://www.ft.com/content/959d08e2-a899-11e9-984c-fac8325aaa04 A Toyota worker loads hydrogen tanks on a production line. For energy majors, hydrogen, which can be produced from fossil fuels, could offer a way of securing a function for their natural gas reserves © Reuters A pasta factory in rural south-west Italy is not the obvious location for an energy project that could show how to cut emissions from Europe’s vast industrial sector.

But the Orogiallo factory in Contursi Terme, in the province of Salerno, made a small slice of history earlier this year when it cooked its pasta using a blend of hydrogen and natural gas that had been injected into the Italian gas transmission grid.

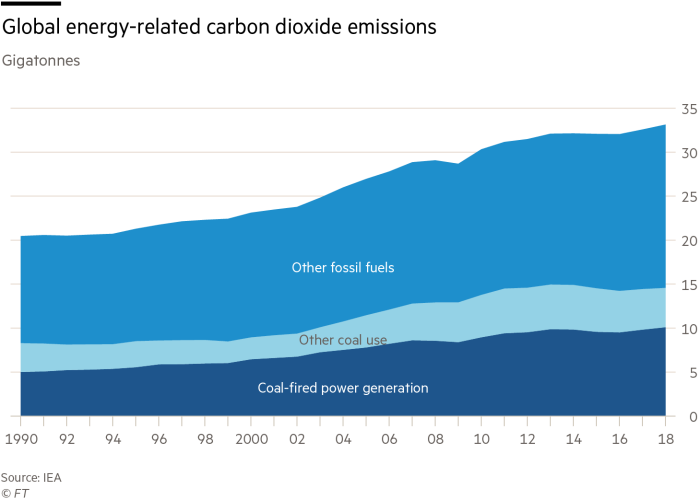

Hydrogen has been touted by scientists and companies as a potential “clean” replacement for fossil fuels such as natural gas as it does not produce carbon dioxide when burnt. Companies and governments are this year renewing efforts to investigate whether hydrogen could help decarbonise key sectors of the global economy, from industry and power to shipping and transport.

The Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA) has described 2019 as a year of “unprecedented momentum” for hydrogen, with 50 policies or targets introduced globally to support its development.

Stephan Herbst, technical general manager for hydrogen at Toyota Motor Europe, said: “The key game-changer is the Paris [climate] agreement.

“There is now a consensus that we need to decarbonise transport and other sectors and we need all energy sources.”

In the case of the Contursi Terme’s project in April, although the proportion of hydrogen used was low at just 5 per cent, the month-long pilot by Italian utility Snam was the first of its kind in Europe to test how safely and reliably it could be injected into the national gas infrastructure, an area that is tightly regulated.

Snam and other gas infrastructure owners in Europe intend to raise the percentage of clean hydrogen used in future projects in the hope that it may one day replace natural gas entirely and secure the future of their assets.

The Snam project is just one example of hydrogen projects planned across the world in coming years by major companies, including Norwegian oil major Equinor, Swedish power company Vattenfall, Japan’s Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, National Grid of the UK and Toyota.

For energy majors, hydrogen, which can be produced from fossil fuels, could offer a way of securing a function for their natural gas reserves in an environment where more governments are adopting policies to end their contribution to global warming.

Transport companies view it as a possible solution for industries such as shipping or freight, or as an alternative to electric vehicles.

But hydrogen has enjoyed several waves of popularity before — in the 1970s, 1990s and early 2000s — and so far failed to take off in the way envisaged by companies such as General Motors, which first produced a hydrogen-powered vehicle in 1966.

The number of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, such as the Toyota Mirai, in circulation last year was just 11,200, according to the IEA, which is small compared with other low emissions cars such as battery electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids.

Previous waves of enthusiasm for hydrogen were snubbed out because they were largely based on its use as a cleaner fuel for passenger cars at a time when oil prices were low, damping appetite among consumers and companies to invest in hydrogen fuelling infrastructure.

Hydrogen — whose clean credentials depend on how it is produced — still polarises opinion, with critics questioning costs and safety. But companies behind hydrogen schemes are hopeful this time will be different.

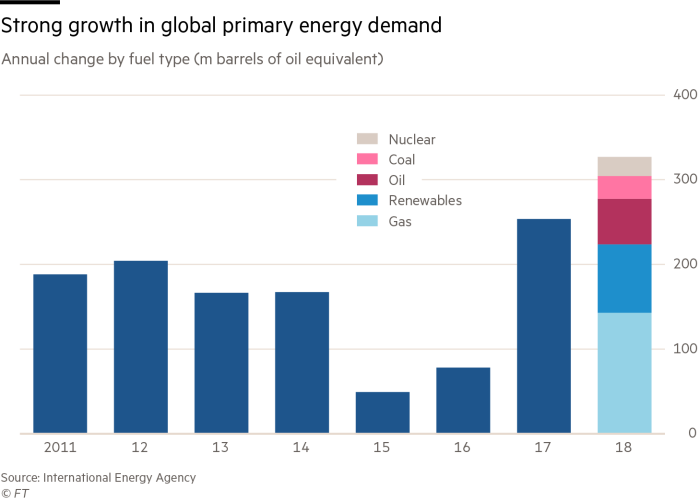

This time the potential uses of clean hydrogen are many. Planned schemes include powering ferries on hydrogen, using it as a replacement for natural gas in domestic boilers, power generation, and as a way of storing excess electricity produced by renewables such as wind and solar on particularly sunny and windy days.

In Eemshaven, on the northern tip of the Netherlands, Swedish energy company Vattenfall is exploring whether part of a gas-fired power plant can be successfully converted to run on hydrogen by 2025.

The immediate effect will be to reduce the emissions from that particular plant. But the wider purpose is to explore whether excess renewable electricity could be used to produce clean hydrogen via electrolysis — a process which also uses water — before being stored. It could then be used to generate electricity again at plants such as the Eemshaven facility during winter or when wind or solar farms were not producing.

“With increasing amounts of renewables in the electricity system, there will be increasing demand for flexible [electricity generation] capacity and seasonal storage,” said Jeffrey Haspels, the project manager for the scheme at Vattenfall.

However, the project, which also involves Norwegian oil company Equinor, Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems and the Dutch energy network company Gasunie, highlights some of the challenges of using hydrogen — in particular, costs.

Mr Haspels estimates the cost at “€1bn-plus” across the value chain, referring to the separate stages of producing the hydrogen, storage and transportation and conversion of the plant. A final investment decision, to be made in 2022, will be dependent on subsidies from the Dutch government.

For this particular trial, the hydrogen will be produced from natural gas as “the situation of having sufficient renewables in the system is not there at the moment in the Netherlands”, said Mr Haspels, although it is envisaged future projects would use electrolysis.

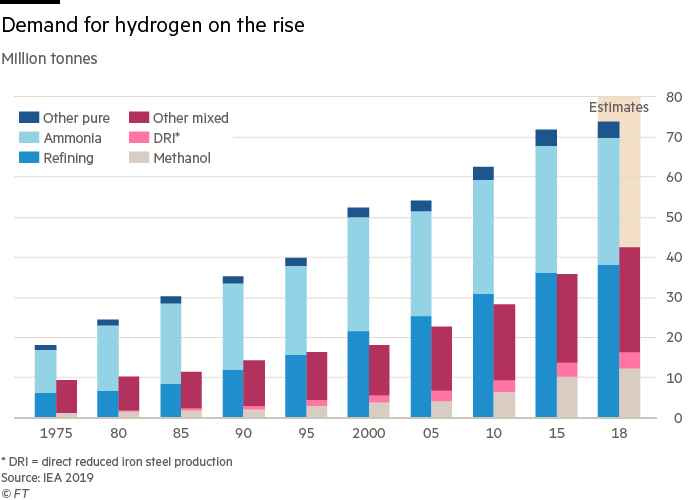

Hydrogen is already widely produced from fossil fuels, about 70m tonnes a year, to make fertilisers or for use in oil refining but this process is heavily polluting. It is responsible for CO2 emissions of about 830m tonnes a year — equivalent to the carbon emissions of the UK and Indonesia combined, according to the IEA.

To make that hydrogen “clean”, the emissions have to be captured, re-used in processes such as fizzy drink manufacturing or stored in depleted oil and gasfields offshore. Many experts believe this will still be the most cost efficient way of producing low emissions hydrogen at an industrial scale, although carbon capture usage and storage technology has its own cost challenges.

“One has to recognise that all this [fresh] momentum and all the talk about hydrogen doesn’t mean the challenges are all of a sudden non-existent,” said Timur Guel, head of energy technology policy at the IEA.

Companies admit early projects will require government funding, but dramatic falls in the costs of other green technologies such as solar and wind provide optimism that the same could happen with hydrogen.

Hydrogen projects may also start to look competitive as costs for emitting CO2 rise in countries that have carbon taxes or emissions schemes, said Emmanouil Kakaras, vice-president and head of research and development at Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems Europe.

“We have to benchmark these [hydrogen] technologies with what we call CO2 avoidance costs,” he added.

In a world where more countries follow the likes of France, Norway, Sweden and the UK in adopting net zero emissions targets, more alternatives to fossil fuels will simply have to be pursued, said Stephen Bull, senior vice-president of wind and low carbon development at Equinor.

“This is beyond business as usual. The decarbonisation strategy we have for [the] electricity market has been relatively successful but it’s nowhere near going to get us to a zero carbon world. This is where we do think hydrogen has a strong role to play.”