New York City set an ambitious new standard for combating greenhouse gas emissions on Thursday, approving a package of climate policies designed to slash energy use in big buildings—the top polluters in the nation's biggest city.

The city found ways to cushion costs for low-income residents while creating jobs and cutting emissions as a 'downpayment on the future.'

The city found ways to cushion costs for low-income residents while creating jobs and cutting emissions as a 'downpayment on the future.'

Supporters say the bills represent the largest emissions cuts adopted by any city worldwide and offer a template others can follow.

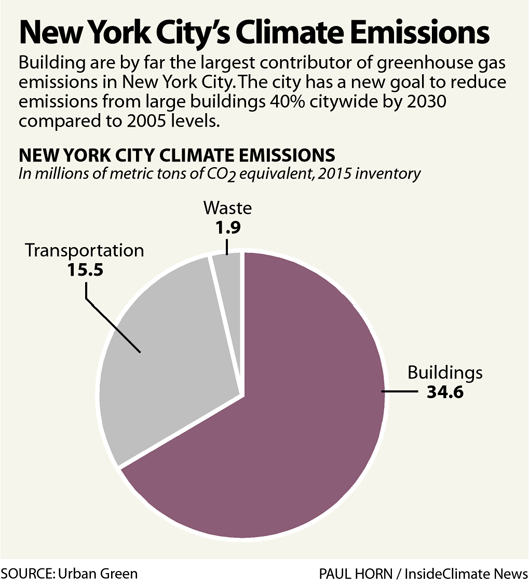

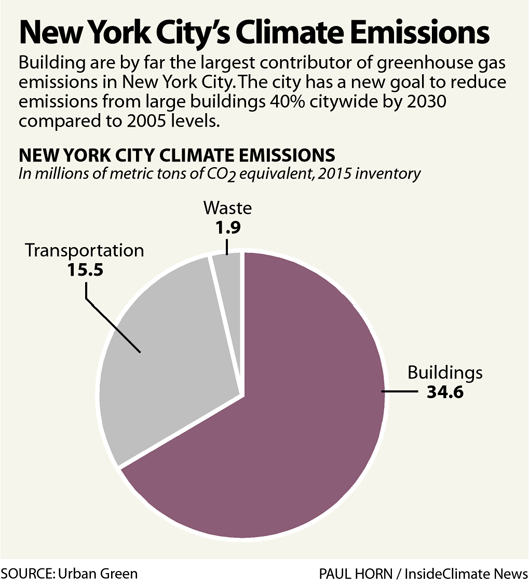

The plans approved by the City Council are expected to cut greenhouse gas emissions from large buildings by 40 percent compared to 2005 levels by 2030—about 26 percent below current levels. Buildings account for two-thirds of the city's emissions, so slashing their energy use is critical to meeting New York's larger climate goals.

"As far as I know, this is the largest carbon reduction initiative for buildings anywhere in the world," said John Mandyck, chief executive of the Urban Green Council, a New York-based nonprofit that helped shape the legislation. He said that beyond the direct impact of the cuts in New York, the bill could help other cities design similar initiatives with flexibility.

The package sets emissions caps for individual buildings and provides a number of ways to meet them. It also includes bills that will increase the number of green roofs, encourage renewable energy, and order a study to look at replacing the 24 large fossil fuel power plants within the city with renewable energy generation.

Council Member Costa Constantinides, who sponsored the buildings emissions bill, called the legislation a "downpayment on the future of New York City," adding, "Today, we sent that message to the world by enacting the boldest mandate to reduce carbon emissions."

The legislation won the support of environmental groups, community activists and unions, who cheered not just emissions cuts but the thousands of jobs they expected to be created by the demand for retrofitting buildings with new insulation and other energy efficiency measures. The city's main real estate association opposed the final bill, arguing that too many buildings would be exempt.

NYC's Broader Climate Plans

NYC's Broader Climate Plans

Beginning under former mayor Michael Bloomberg, New York City adopted one of the most ambitious climate plans of any city in the country, aiming to cut emissions 30 percent by 2030. Mayor Bill de Blasio continued those policies, and in 2014 pledged to cut city emissions 80 percent by 2050.

The city updated its building codes, worked to reduce waste and helped spread solar power development, but it had been unable to find a way to tackle its largest source of emissions: existing buildings.

While some cities, including Atlanta and Cleveland, have pledged to get all of their electricity from renewable sources, electricity use only accounts for about a third of the emissions associated with New York City's buildings: the bulk comes from heating with oil or natural gas.

"This new law is the first step in putting the regulatory approach behind the 80 by '50 mandate," Mandyck said.

How the Bill Boosts Renewable Energy

The bill, which de Blasio has said he will sign, divides buildings into categories based on size and use, and sets hard emissions caps for each category. City-owned buildings will have to cut emissions fastest. Beginning in 2024, buildings that exceed their caps will have to pay fines—or buy renewable energy credits.

Mandyck praised the provision that allows building owners to purchase renewable energy credits, which help to spur a shift to carbon-free electricity. That flexibility makes the ambitious targets easier to achieve, and it also helps to finance the renewable energy projects that the cities will need to meet its climate goals.

"It's a new way to think about how you can drive carbon reductions down in a city," Mandyck said. "We're in a global climate, we need to find global climate solutions."

A Way to Protect Low-Income Residents

A number of types of buildings, including houses of worship and any with a rent-regulated apartment, do not have to meet the emissions caps, but will instead be required to implement low-cost measures such as insulating pipes and windows and installing controls on radiators.

The carve-out for rent-regulated apartments is meant to ease the burden on poorer residents, since landlords would pass costs on to tenants. Buildings smaller than 25,000 square feet, which account for about 40 percent of the city's building space, are not covered.

New York's powerful real estate industry criticized the bill, saying it would fail to meet its goals because the emissions caps do not cover enough of the city's building stock. The Real Estate Board of New York also said the bill would discourage energy-intensive businesses, such as the technology sector.

Supporters pointed out that the city's large luxury apartment buildings have an outsized emissions footprint.

The city found ways to cushion costs for low-income residents while creating jobs and cutting emissions as a 'downpayment on the future.'

The city found ways to cushion costs for low-income residents while creating jobs and cutting emissions as a 'downpayment on the future.'  NYC's Broader Climate Plans

NYC's Broader Climate Plans