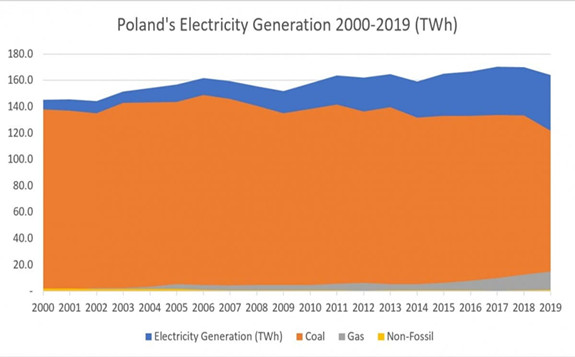

Every severe economic crisis shakes the basic foundations of seemingly mainstream policies and ideas and makes one wonder whether the recession’s impact could have been mitigated by timely and ambitious decisions. Despite being the country with the lowest GDP drop this year in Europe, Poland seems to be smitten by such nationwide deliberation and perhaps unsurprisingly substantial attention is dedicated to the future of coal. For decades Poland was among the world’s top coal producers, to the extent that up to today no EU member burns more coal than Poland (75% of its electricity generation). Yet the intra-European pressure to canvass a greener and more sustainable future has brought Poland to the least probable of candidates, nuclear energy.

Replacing coal with other forms of energy will prove to be not only an economic challenge for Poland, in many ways coal is ingrained in the regional psyche of South and Southwest Poland (Silesia) where coal production has already started in the late 18th century. After reaching an all-time annual high of 266 million tons in 1988, Poland’s consumption has first plummeted on the back of the post-Soviet demand crunch and then started to decline by an average 2% year-on-year in the new millennium. Despite a generally declining trend, coal still matters a lot to Poland, home to Europe’s largest coal plant (in Belchatow, generating some 20% of Poland’s electricity), remaining the most coal-dependent economy in Europe with a population of almost 40 million.

Despite its coal reserves bounty, Poland has started to import substantial amounts of better-quality anthracite which has raised political alarms with the ultra-conservative ruling party (PiS) banning state-owned entities to participate in such transactions, although private firms are still allowed to do so. Yet what can Poland do – endowed with vast reserves of lower-than-necessary-quality coal and compelled to align with the European Union’s going green (not to mention that the current government was voted into power with a very powerful pro-coal platform)? The Polish government seems to be siding with a gradual phase-out, perhaps not as ambitious as the 2036 coal halt deadline mentioned in Polish newspapers yet still aspirational enough to convince the EU that Warsaw means it, despite being the only EU country not to commit to the 2050 carbon neutrality objective.

Two main trends will push gradually coal into the red zone economically – increasing production costs as miners have to dig deeper and deeper and Europe’s emissions trading scheme that penalizes the coal industry with particular force. The answer to Poland’s energy woes might lie in the realm of renewables, all the more so as wind energy has been making some real headway. Poland’s onshore wind capacity from complete zero some 12 years ago to 5.9 MW installed capacity yet as Polish analysts point out themselves the country will not be able to supplant decreasing coal capacities by relying on onshore wind solely; for a tangible paradigm shift Warsaw would need to tap into its windiest part, the Baltic Sea. Yet even this would not be enough and here enters the latest, perhaps missing, piece to the puzzle – nuclear energy.

Poland has had a contorted history with nuclear energy. Although the main thrust of the 1986 Chernobyl catastrophe radiation front fortuitously spared most of Poland, the radiation levels attested at the Polish-Soviet border still make it the third most-affected nation. This is itself would be enough to substantiate Poland’s anti-nuclear stance. Yet there is more – Poland has been one of the staunchest opponents of the Ostrovets Nuclear Plant in Belarus, going as far as to banning potential nuclear imports from Belarus under the pretext of it “being unsafe”. Yet Poland itself has already flirted with the idea of buying into nuclear – Lithuania’s Visaginas nuclear plant, which was supposed to replace the Soviet-era Ignalina power plant but was ultimately cancelled due to it being thoroughly loss-making, might have seen Polish participation and investment.

In 2009, the Polish Economy Ministry has called for the construction of at least 2 nuclear plants which were supposed to provide around 15% of electricity by 2030, with coal’s share decreasing by the same measure to 60%. After a decade spent on creating on sorting out regulatory issues, Poland now seems fully committed to get the nuclear ball rolling. According to the newly formed Ministry of Climate, the construction of the 1st reactor is expected to take place in 2026 and the nuclear plant would be commissioned around 2033/2034 with further reactor additions in the follow-up. The location of the nuclear plant is still undecided, yet everything seems to be pointing Zarnowiec in Pomerania – as it happens, the site where Poland had 4 VVER-440 nuclear units under construction in the 1980s, only to abandon the project altogether once the country has shed its Soviet ties.

Judging by the preferences of Polish authorities, Warsaw wants the United States to build the nuclear plant – an odd choice given the tender-based nature of the deal, rendered even weirded by US firms massively underperforming potential openings abroad. The economic rationale behind Poland’s nuclear plans is fairly straightforward – as coal is increasingly becoming beyond the producer’s means, natural gas and oil is being imported (does not matter if it is from Russia or Norway) and thus always subject to the authorities’ antipathy, nuclear turned out to be the most cost-effective conventional solution. The environmental rationale is also evident – nuclear is to replace coal as the baseload capacity for the country’s north, with no carbon emissions attached to it. All the rationales look good on paper, however, telling that to the approximately 100 000 miners all across Poland is a straight-out political suicide.

Graph: Poland’s Electricity Generation in 2000-2019 (in Tera-Watthours).