After the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on its economy, there are signs that Argentina’s once burgeoning oil industry is coming back to life. Exploration and development drilling has recommenced in the all-important Vaca Muerta, on which Buenos Aires has pinned its hope for a petroleum led economic recovery. National oil company YPF recently announced it would add three drill rigs to its unconventional oil and natural gas operations in the region. This comes after the company virtually suspended operations in the Vaca Muerta in March in response to the pandemic and the central government’s measures aimed at containing the coronavirus.

The late Jurassic to early Cretaceous age geological formation is billed as the most promising and richest unconventional oil and natural gas play outside of the U.S. Its development has become central to the government’s plans to revive Argentina’s fragile economy. The formations development was responsible for Argentina’s hydrocarbon output growing significantly to see the Vaca Muerta account for around a quarter of the country’s total natural gas production.

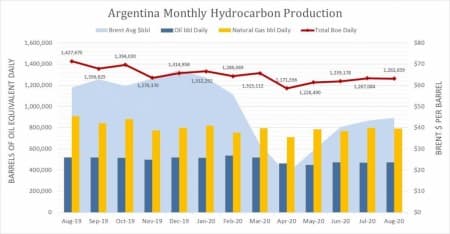

Nonetheless, the latest government data indicates a recovery to pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels is a long way off, regardless of the recent uptick in drilling activity. By August 2020 Argentina’s total oil and natural gas production was 1,262,659 barrels of oil equivalent daily which was 1% lower than the previous month and a worrying 11.5% lower year over year.

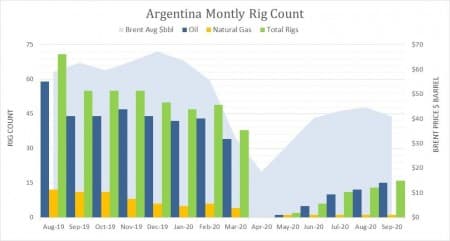

The latest Baker Hughes rig count data, which can be used a proxy measure of activity in Argentina’s energy patch, shows that drilling activity is rising since April 2020. By the end of September 2020 there were 16 operational drill rigs, three higher than a month earlier and eight times greater than May. This, however, was still less than a quarter of the 71 rigs operating at the end of August 2019.

Data in Natural Gas Intelligence shows that hydraulic fracturing activity in Argentina has all but collapsed. During August only 98 fracking stages were completed compared to an average of 700 a month during 2019. These developments highlight the urgency of attracting further investment in Argentina’s petroleum industry if the full potential of the Vaca Muerta is to be unlocked and Buenos Aires is to realize its dream of revitalizing the economy.

The Vaca Muerta shale formation’s potential is vast. The U.S. EIA, which bolstered its estimates for the formation in late-2019, estimates the Vaca Muerta has technically recoverable resources of 308 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 16 billon barrels of oil and other petroleum liquids. The EIA compares the geological formation to the prolific Eagle Ford shale in southern Texas. It is estimated that only around a twentieth of the Vaca Muerta’s 8.6 million acres has entered the development phase, underscoring the need for more investment if those vast hydrocarbon resources and consequent wealth are to be tapped. Those numbers illustrate the considerable potential held by the Vaca Muerta and why Buenos Aires holds such significant hopes that its development can drive an economic revival.

Even before the pandemic forced YPF and other oil companies to shutter operations in Colombia, the nascent oil boom was facing headwinds. The prolonged price slump saw energy majors focus on developing projects in low-cost jurisdictions like offshore Brazil and Guyana rather than higher-cost unconventional oil. The Vaca Muerta’s estimated breakeven price for new developments is pegged at $50 a barrel and between $45 to $50 per barrel for operational assets, making investing in developing acreage in the formation unattractive when Brent is selling for around $42 per barrel. That is compared to Brazil’s pre-salt offshore fields which have projected breakeven prices of $35 to $45 per barrel and Guyana where it is currently pegged at $35 per barrel and expected to fall lower.

The threat of oil nationalism looms large over Argentina’s energy patch. The election of Peronist Alberto Fernández as President in October 2019 and the appointment of Cristina de Kirchner as vice president brought back painful memories of her nationalization of YPF in 2012 when she held Argentina’s top job. That saw a significant ratcheting up in the perceived degree of political risk for offshore oil companies seeking investment in the Vaca Muerta. Even Fernández’s reassurances and implementation of a $45 per barrel price floor for oil produced in Argentina has done little to attract investment or significantly boost activity.

Late last month Buenos Aires moved to tighten capital controls in a bid to protect foreign currency reserves, slow the peso’s fall in value and prevent an outflow of capital because of the peso’s sharp devaluation. That will further weigh on the confidence of energy investors. It has also raised the risk of a wave of defaults among Argentine companies. This is because companies with debt repayments of greater than $1 million monthly will be forced to only repay 40% of the amount outstanding in foreign currency. That in effect, will force companies to refinance the remainder, pushing them closer to failure.

There is a growing sense of urgency in Fernández’s that the economic crisis must be dealt with. During May 2020, the country defaulted on its foreign debt for the second time in 20 years and the IMF believes that Argentina’s economy will contract by almost 10% during 2020. As the economy worsens there the likelihood of further government intervention through such measures as currency and capital controls. It also increases the risk of resource nationalism. Combined those facts further reduce Argentina’s attractiveness as an investment destination for international petroleum companies.

This article is reproduced at cleantechnica.com