A cooling tower emblematic of Germany's nuclear aversion has been toppled near Koblenz. Seven reactors are still operational in Germany, with the last due to be phased out in late 2022 amid a drive to renewables.

Mülheim-Kärlich, a former German nuclear plant — where dismantling operations began in 2004 after its brief power-generating life ended in 1988 amid bitter controversy — lost its cooling tower on Friday, marking the latest stage in a 40-year saga that's cost billions .

Two remote-controlled excavators — one fitted with a giant hammer, the other with large pliers — removed last props at the base of the hollow 80-meter-high (263-foot) structure, triggering the collapse of what was left of the tower.

"The collapse came a little earlier than expected in the simulations," demolition project leader Olaf Day told regional public broadcaster SWR.

Read more: German renewables deliver more power than coal and nuclear power

The tower's top half — that once loomed up to 162 meters high — had in recent years been chewed down by a hydraulic concrete-gobbling contraption that circumnavigated its rim.

'Eyesore' gone at last

The state premier for Rhineland-Palatinate (RP), Malu Dreyer, who watched Friday's spectacle, thanked the local community and environmentalists for pushing for the removal of what she called an "eyesore" in the Koblenz-Neuwied basin , surrounded by hills, near where the Moselle river enters the Rhine.

The demolition signaled "the end of dangerous atomic energy in Rhineland-Palatinate," she said. France retains nuclear power reactors upwind from RP's borders, including Cattenom in the upper reaches of the Moselle.

Ten more years of demolition pending

The site's complex clearance, involving the removal of 500,000 tons of concrete and metal — plus potential decontamination efforts if required — is expected to take until 2029.

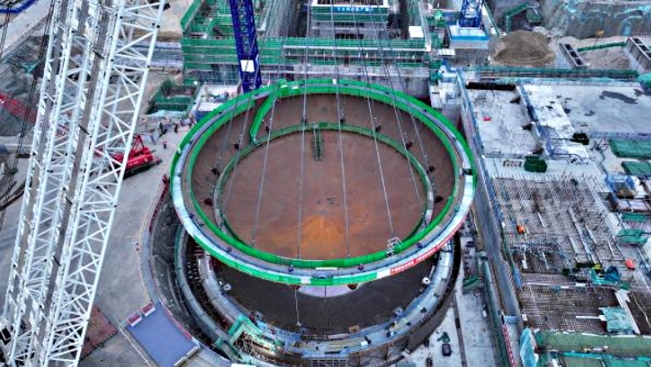

Remaining structures on the Mülheim-Kärlich site — formerly fenced-off to keep protesters out — include its vacated reactor dome. The land alongside the Rhine is eventually destined for commercial use.

The plant originally cost its owner, the utility company RWE, €3.6 billion ($4 billion); its demolition will end up costing another €1 billion, according to the regional public broadcaster SWR.

Kohl-era project

Mühlheim-Kärlich, with 1,300 megawatts capacity, got its go-ahead in 1975 from the-then conservative Rhineland-Palatinate government led by its then-premier Helmut Kohl — later Germany's chancellor.

In 1988, Germany's federal BVG administrative court halted the project after testing and only 13 months of regular power generation, citing deviance from approved construction plans and its siting in a volcanic zone with underground faultlines.

Neighbors and anti-nuclear protesters who had slung giant banners high on the cooling tower saw their fears confirmed by Ukraine's 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

During 10 subsequent years of legal appeals, RWE staff maintained the plant in case it was reactivated, but in a 1998 final ruling the Leipzig-based BVG voided the building permit because the quake risk had been overlooked. RWE decided in 2000 to proceed with closure.

Safety maintained, said RWE

The Essen-based company — also involved in controversial brown coal extraction — maintained that neither technical nor reactor-safety deficiencies were proven at Mülheim-Kärlich but reached a cost trade-off with German authorities to recover lost earnings via generation at other plants.

By 2002, RWE said, 1,700 tons of radioactive material, including fuel rods, had been removed and put in a repository, pending Germany's decision due by 2031 on a final underground nuclear waste disposal site.

One of Mulheim-Kärlich's stream-fed generators was sold to Egypt.

Search for renewable alternatives

Germany's initial nuclear phase-out decision of 2001 — canceled by Angela Merkel but then suddenly reinstated after Japan's Fukushima meltdown in 2011 — culminated in a 2017 deal in which four utilities agreed to pay Germany €24 billion for final storage, despite critics' doubts whether this figure would suffice.

Germany intends to replace the 12 percent of its electricity generated using nuclear power through renewables such as wind and solar-generated power.

A coal-fired phase-out by 2038 poses further challenges as energy companies try to persuade residents to accept extra cables and pylons and wind turbines dotted across the countryside.