Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) have reported a breakthrough in developing a next-generation thermochromic window that not only reduces the need for air conditioning but simultaneously generates electricity.

Image credit: NREL

Image credit: NREL

Heat generated by sunlight shining through windows is the single largest contributor to the need for air conditioning and cooling in buildings. This new technology aims to address that by maximising energy efficiency.

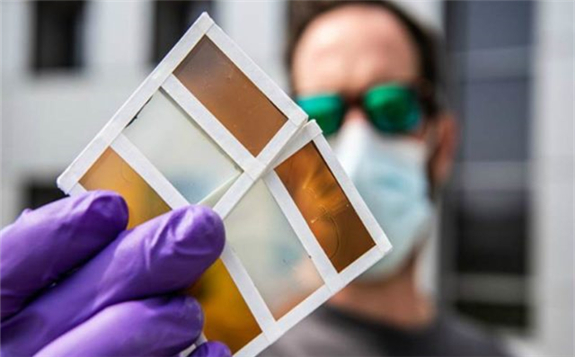

The technology, termed “thermochromic photovoltaic,” allows the window to change colour to block glare and reduce unwanted solar heating when the glass gets warm on a hot, sunny day. This colour change also leads to the formation of a functioning solar cell that generates on-board power.

Thermochromic photovoltaic windows can help buildings turn into energy generators, increasing their contribution to the broader energy grid’s needs.

The newest breakthrough now enables myriad colours and a broader range of temperatures that drive the colour switch. This increases design flexibility for improving energy efficiency, as well as control over building aesthetics that is highly desirable for both architects and end-users.

The research builds upon earlier work at NREL into a thermochromic window that darkened as the sun heated its surface. As the window shifted from transparent to tinted, perovskites embedded within the material generated electricity. Perovskites are a crystalline structure shown to have remarkable efficiency at harnessing sunlight.

“A prototype window using the technology could be developed within a year,” said Bryan Rosales, a postdoctoral researcher at NREL and lead author of the paper Reversible Multicolor Chromism in Layered Formamidinium Metal Halide Perovskites, which appears in the journal Nature Communications.

His co-authors from NREL are Lance Wheeler, who developed the first thermochromic photovoltaic window, Taylor Allen, David Moore, Kevin Prince, Garry Rumbles, and Laura Schelhas. Other authors are Laura Mundt from SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and Colin Wolden from Colorado School of Mines.

The first-generation solar window was able to switch back and forth between transparent and reddish-brown colour, requiring temperatures between 150 degrees and 175 degrees Fahrenheit (65-80 degrees Celcius) to trigger the transformation. The latest iteration allows a broad choice of colours and works at 95 degrees to 115 degrees Fahrenheit (35 -46 degrees Celcius), a glass temperature easily achieved on a hot day.

The scientists sandwiched a thin perovskite film between two layers of glass and injected vapour. The vapour triggers a reaction that causes the perovskite to arrange itself into different shapes, from a chain to a sheet to a cube. The colours emerge with the changing shapes. Lowering the humidity returns the perovskite to its normal transparent state.