“Microreactors are an exciting innovation that completely flips the technology story for nuclear energy,” Alex Gilbert, a project manager for nuclear power think tank the Nuclear Innovation Alliance, told CNBC.

Historically, nuclear energy producers aimed to be competitive with “economies of scale,” meaning they save money by being massive, Gilbert said. That strategy, however, often results in construction projects being mired in delays and cost overruns, like the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia, where estimates for the project have ballooned from $14 billion to an estimated $27 billion or more.

“Microreactors promise to turn this paradigm on its head by approaching cost competitiveness through technological learning,” Gilbert said.

Oklo is the brainchild of the husband-and-wife co-founder team, Jacob DeWitte and Caroline Cochran, who met when they were teaching assistants in 2009 for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Reactor Technology Course for utility executives with nuclear power plants as part of their grid.

Very small nuclear reactors

Bill Gates’ fission company, TerraPower, is already selling the idea that it’s building smaller reactors than are typically used in conventional nuclear power plants.

But DeWitte said Oklo will build reactors “far smaller” than the ones TerraPower is building. TerraPower’s main nuclear reactor, the Natrium, will have a capacity of 345 megawatts of electrical energy (MWe), where the first Oklo reactor, called the Aurora, is expected to have a capacity of 1.5 MWe, making it a true micro-reactor. A 2019 report prepared by the Nuclear Energy Institute defined micro-reactors to be between one and 10 MWe. Other companies in the space include Elysium Industries, General Atomics, HolosGen, NuGen and X-energy, to name a few.

Oklo plans to own and operate these micro-reactors, Cochran said, and customers could include utility companies, industrial sites, large companies, and college and university campuses, DeWitt said.

“Today’s large reactors fit the bill to meet city-scale demand for clean electricity,” Jonathan Cobb, senior analyst at the World Nuclear Association, told CNBC. “But smaller reactors will be able to supply low-carbon electricity and heat to remote regions and other situations where gigawatt-scale capacities would be too much.”

Because of their small size, micro-reactors are faster to build than conventional reactors. “Less than a year to construct the powerhouse is a conservative estimate,” Cochran told CNBC.

Using waste as fuel

Oklo is planning to build a specific kind of nuclear power generator called a fast reactor that is meant to be more efficient than traditional generators, allowing it to get energy out of already spent fissile fuel.

In nuclear fission, when a larger atom is split into two, the resulting smaller nuclei are “going about 15,000 kilometers per second,” DeWitte told CNBC.

“A ‘fast reactor’ operates in a way that does not slow down the neutrons, in comparison to ‘thermal reactors’ that contain a moderator, water in today’s reactors, that slow down the neutrons,” Marc Nichol, NEI’s senior director of new reactor deployment and the project lead for the 2019 report, told CNBC.

Because fast reactors do not slow down the nuclei after the fission reaction, they are “harder to catch, so you need more fuel” to power a fast reactor, DeWitte said. But fast reactors are also more efficient with the fuel they do use, he said.

The technology has been around since the 1950s, according to the World Nuclear Association. Currently, there are 20 fast neutron reactors operating around the world, and globally, Russia is leading the development of fast reactor technology, the association says.

“These reactors have been built and operated before. So they’re ready to go,” DeWitte said. “In some ways, the story about what has been done with these reactors is very unheralded, which is a really cool opportunity.”

One key benefit of the technology is that fast reactors are able to use the waste from conventional nuclear reactors. They can “unlock the rest of the energy in the fuel,” DeWitte said.

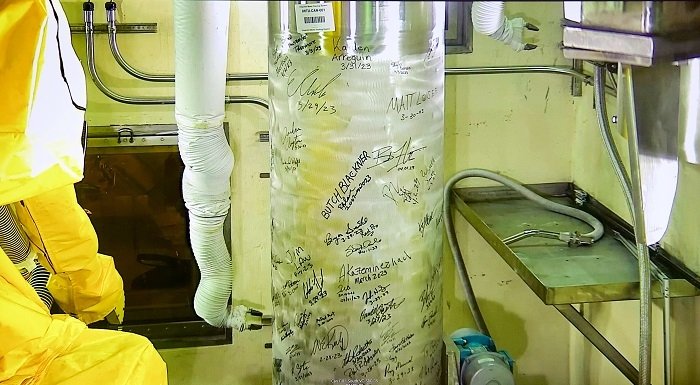

In February 2020, the Idaho National Laboratory, part of the U.S. Department of Energy’s system of national laboratories that focuses on nuclear energy research and development, announced it was going to give Oklo access to nuclear waste so it can develop and demonstrate its fast reactor technology.

“Oklo is planning to use uranium recovered from previously used Experimental Breeder Reactor II (EBR-II),” Jess Gehin, an associate laboratory director of the Nuclear Science and Technology Directorate at the Idaho National Laboratory, told CNBC. The EBR-II nuclear reactor operated from 1964 to 1994, he said. “As a result, the materials, which were previously destined for disposal, can be used to produce more energy.”

“The reuse of materials has been long an option to better utilize natural resources, uranium in this case, as well as decreasing the amount of used fuel that must be ultimately disposed,” Gehin said. “This is a common practice in some countries like France but not in the U.S., as economics do not favor this path.”

There is some recent positive movement. On Thursday, Oklo announced a partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy to help commercialize the electrorefining technology that advanced fast reactors use in the United States. The technology itself “has already been demonstrated in the U.S.,” Cochran said.

Pulling more energy out of the fuel also shortens the time it takes the toxic component of radioactive waste to decay, DeWitte told CNBC.

“It changes the waste picture as a whole,” DeWitte said. “What we’ve now done is take waste that you have to think about managing for 100,000 or a million years ... and now you’ve actually changed it into a form where you think about it for a few hundreds, maybe thousands of years.”

What is left Oklo could turn into glass logs, in a process called vitrification, and bury those in deep bore holes underground, DeWitte said.

Oklo’s fast reactors will be housed in A-frame structures that are “aesthetically pleasing,” Cochran said. Architectural Digest calls the building “sleek.” The A-frame design is also good for protection against snow and other precipitation.

Oklo says the fast reactors will be self-sustaining and not require any human operators.

The goal is to have “a number of plants operating by the mid-2020s,” Cochran told CNBC.

What stands in the way

Oklo has big plans, but the company still has regulatory hurdles to overcome, and some safety experts dispute the company’s contention that the micro-reactors can run without people.

Oklo launched in 2013 and began having discussions with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission in November 2016. In June 2020, Oklo’s application to build an advanced reactor was accepted for review by the commission.

However, ”‘accepted for review’ does not mean ‘approved’ to build,” David McIntyre, spokesperson for the commission, told CNBC. “Before Oklo is allowed to construct and operate the reactor, it must receive a license to do so.”

Leaving the microreactors without human guards is not safe, in the view of Edwin Lyman, director of Nuclear Power Safety at the Union of Concerned Scientists, who has put together an extensive report on the safety of advanced nuclear technologies.

“The biggest problem is that because the economics is so poor — they are really going against economics of scale — that the microreactor vendors are pushing to reduce (or even eliminate entirely) personnel such as operators and security officers,” Lyman told CNBC Make It. “But even a very small reactor contains enough radioactive material to cause a big problem if it is sabotaged, and none of these reactors have demonstrated they are so safe that they can function without operators.”

The fuel that microreactors use “must be rigorously guarded against theft,” Lyman said.

Frank N. von Hippel, senior research physicist and professor of public and international affairs emeritus at Princeton University, also raised concerns about the economics of small reactors. And he, too, worries about the expense of what he considers necessary security.

“One issue would be what kind of security arrangements the regulatory authorities will require in a remote location: multiple guards around the clock could consume much of the gross revenue,” von Hippel told CNBC.

In response to these concerns, Cochran said there are already nuclear reactors operating both in the United States and globally that “operate without security forces and have impeccable security records over many decades.”

It’s also vital to realize that these plants are small and as such “cannot reach the scale needed for broad decarbonization alone,” Gilbert said. “Microreactors can help decarbonize smaller grids but they are only the first step we need in nuclear innovation to meet our climate challenges.”

But, Cochran said, the urgent need to transition to clean energy is pointing to a strategy of “let’s use all the tools we have.”