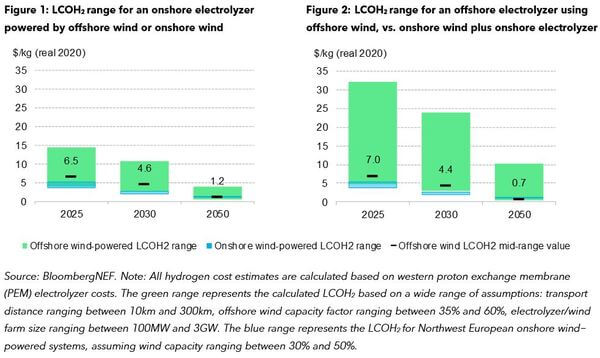

Offshore wind could become an important way to produce hydrogen at scale. The project pipeline is growing rapidly, costs are falling and non-economic factors are poised to boost uptake. BloombergNEF estimates that a mid-range price for offshore wind-to-hydrogen will be around $7/kg in 2025, dropping to $1/kg by 2050.

The rise of offshore wind-to-hydrogen

The growing need to reduce emissions beyond the electricity sector has ignited interest in renewable hydrogen (H2). Offshore wind is one way to produce renewable hydrogen at scale. It is early days but the project pipeline is growing rapidly, with over 17GW of announced electrolyzer capacity. Orsted, RWE, Siemens and Shell are among those with projects in the pipeline.

Offshore wind-to-hydrogen activity is concentrated in the North Sea, off the U.K., Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. This is because of outstanding wind resources, extensive subsea gas networks, established offshore wind supply chains, supportive policy and significant expected demand for hydrogen. Many of these drivers also exist in other regions.

Cost are high, but set to fall

It is cheaper to produce hydrogen today using fossil fuels as opposed to onshore wind or solar. Using offshore wind to produce hydrogen is more expensive still. The need for subsea electricity transmission and hydrogen pipeline transport further escalates costs.

BloombergNEF estimates the mid-range LCOH2 to be about $4.6/kg in 2030 for an offshore wind project with an onshore electrolyzer. Costs however vary significantly by site and project size. They are also falling: the mid-range LCOH2 falls to around $1.0/kg by 2050 as both offshore wind projects and electrolyzers get cheaper. By then, it is cheaper to use offshore rather than onshore wind to produce hydrogen. Non-economic factors, such as H2 consumption mandates, or government subsidies will be key to uptake in the meantime.

Most projects due to be commissioned by 2025 are demonstration projects built to identify regulatory, commercial and technical challenges. Commercial success post-2025 will depend on a few factors. Countries with ample coastlines and scarce land for either renewable generation or hydrogen production may instead seek to develop these resources offshore, even if they cost more. Average offshore wind projects located in North Sea will grow to gigawatt-scale by 2030 as opposed to megawatt-scale onshore projects. These projects can also access high wind speeds at sea, meaning they generate huge amounts of electricity. This will be important if demand for hydrogen scales sufficiently. Countries with energy security concerns may also favor locally produced hydrogen rather than increasing their reliance on imports. Coupled with land-use restrictions, it creates an opportunity for offshore wind.

Project design choices

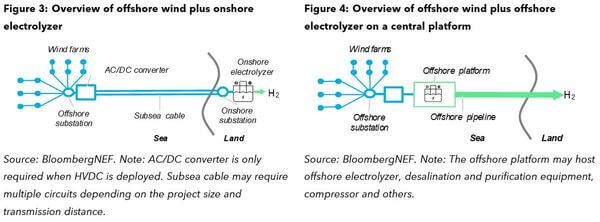

Multiple different project configurations exist, and BloombergNEF focused on two common approaches in the study.

Offshore wind plus onshore electrolyzer. Electricity is transmitted via a subsea cable to an onshore electrolyzer to produce hydrogen (Figure 3).

Offshore wind plus an offshore electrolyzer on central platform. The project produces hydrogen offshore and transports it through a dedicated pipeline to shore (Figure 4).

Projects using offshore rather than onshore electrolyzers tend to be more expensive until 2030, but then are preferred.

Project design choices

Multiple different project configurations exist, and BloombergNEF focused on two common approaches in the study.

Offshore wind plus onshore electrolyzer. Electricity is transmitted via a subsea cable to an onshore electrolyzer to produce hydrogen (Figure 3).

Offshore wind plus an offshore electrolyzer on central platform. The project produces hydrogen offshore and transports it through a dedicated pipeline to shore (Figure 4).

Projects using offshore rather than onshore electrolyzers tend to be more expensive until 2030, but then are preferred.