After a harsh 2020 where a combination of sharply weaker oil prices and the COVID-19 pandemic caused investment and production to plummet, questions are emerging as to the viability of Colombia’s hydrocarbon sector. Petroleum once seen as a powerful driver of the strife-torn Latin American country’s economic miracle is fast emerging as a threat to Colombia’s economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Crude oil is Colombia’s primary legal export (Spanish) having generated $9 billion for the first 9 months of 2021 or 32% of the Andean country’s total exports by value. It is then coal and coffee, which at 12% and 7% respectively, that round out Colombia’s top 3 exports by value. Petroleum is also responsible for 3% (Spanish) of the crisis-riven country’s gross domestic product. For those reasons, Colombia’s petroleum industry is a key driver of the economy and the local currency, the peso, is correlated to the price of crude oil.

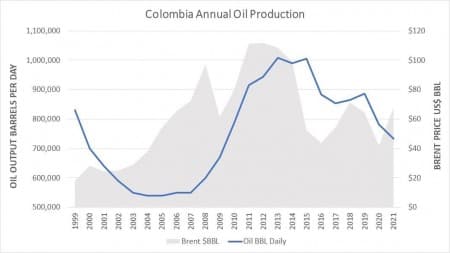

The sharp decline in oil prices, which occurred from late-August 2014 onwards, followed by the pandemic sharply impacted Colombia’s economically crucial petroleum industry. Those events were responsible for industry investment plunging sharply since 2015. During 2020 alone, investment crashed by 48% compared to a year earlier to $2.05 billion, the lowest level since 2016 when Brent plummeted to less than $27 per barrel, primarily due to the oil price collapse sparked by the pandemic. After peaking at an average of just over one million barrels per day during 2013 Colombia’s oil output has steadily declined, hitting a multi-year average monthly low of 649,151 barrels per day during June 2021 as anti-government protests exacerbated existing production headwinds. By 2020, Colombia’s oil production averaged 781,300 barrels per day, the lowest level since 2009, and has only averaged 733,561 barrels daily (Spanish) from January to September 2021.

One million barrels of crude oil per day was seen by the national government in Bogota as the ideal production level to drive Colombia’s once impressive economic growth, which hit a multi-decade high of 6.9% in 2011 as the last oil boom and production gained momentum. Since then, growth has effectively stalled because of declining crude oil production, softer petroleum prices and the fallout from the pandemic. During 2017 gross domestic product only expanded by a meagre 1.4% which increased to 2.6% and then 3.3% by 2018 and 2019 respectively before plunging by nearly 7% during 2020 as the pandemic sharply impacted Colombia’s economy.

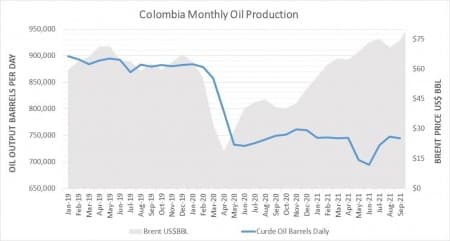

The strife-torn Andean country is struggling to restart its oil industry and grow production as well as oil reserves. During September 2021, Colombia pumped an average of 744,173 barrels of crude oil per day, which was half a percentage point lower than August and nearly 1% less than for the same period in 2020.

This indicates that unless there is a notable increase in crude oil production during the final three months of 2021 Colombia will pump less petroleum this year than for 2020 when the pandemic caused output to plummet.

Production growth remains problematic despite the Colombian Petroleum Association forecasting that oil industry investment will expand by at least 51% year over year to $3.1 billion for 2021. This is evident from the latest Baker Hughes Rig Count, which is a good proxy measure of industry activity. At the end of October 2021, there were 23 active drill rigs in Colombia, which is two greater than a month earlier, nearly double the 12 active rigs for the same period in 2020 but six less than for September 2019.

The inability to expand production despite the massive 2021 rally, where Brent is up by a stunning 56% since the start of the year to be selling at nearly $80 per barrel, points to broader issues that are hampering the petroleum industry’s recovery. Among the headwinds are considerable security risks with attacks upon pipelines and other critical industry infrastructure including wellheads impacting operations. Pipelines are the only cost-effective means of transporting crude oil across the Andean country’s rugged terrain, however, because they pass through remote regions, they are vulnerable to sabotage and being illegally tapped with oil theft a growing problem in Colombia.

Colombia’s petroleum pipelines, notably the 210,000 barrels per day Cano Limon-Covenas pipeline, are popular targets for sabotage by leftist guerillas. The pipeline was last attacked in early 2021 and authorities prevented another planned assault by Colombia’s last remaining leftist guerilla group the National Liberation Army (ELN – Spanish initials) three months later. The ELN also claimed responsibility for a series of October 2021 attacks on energy infrastructure owned by Colombia’s national oil company Ecopetrol near the La Cira Infantas oil field located near the city of Barrancabermeja. Civil unrest is also a constant threat for Colombia’s oil industry, particularly with its social license deteriorating in regional communities. During May and June 2021 oil output fell sharply, to a multi-year low of 650,884 barrels per day, as anti-government protests swept the country in response to a botched attempt to hike taxes. Oilfield invasions and blockades by local communities are a regular occurrence. Rising insecurity is also a result of a sharp uptick in cocaine production as well as growing lawlessness in the remote regions where Colombia’s oil industry operates, which has led to a substantial increase in massacres.

Another key risk arising from heightened security risk is a lack of exploration activity, which means there is little likelihood of Colombia’s meager proved oil reserves (Spanish) of 1.8 billion barrels. Those reserves at the current rate of production have an estimated production life of just over 6 years, highlighting the urgency with which Colombia needs to ramp up oil exploration and development activities. The sharp increase in violence, mostly in remote regions where Colombia’s petroleum reserves are located, is a significant deterrent to investment in onshore operations, especially the exploration of remote hydrocarbon basins. Aside from deterring foreign energy investment, those events are impacting Colombia’s onshore oil industry’s operations leading to lower production and a lack of exploration activity.