China has set itself a target of achieving carbon neutrality by 2060, but how it will reach the goal is unclear.

China is the world’s biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions and is seen as critical to global climate efforts. Photo: AP

China is the world’s biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions and is seen as critical to global climate efforts. Photo: AP

According to a recent report by oil and gas multinational Royal Dutch Shell, one way China could build a carbon-neutral energy system before 2060 is by focusing on hydrogen, biofuels and carbon-removal technologies, while phasing out fossil fuels.

In its analysis, electricity’s share of China’s energy consumption is projected to rise to almost 60 per cent in 2060, from 23 per cent today, with buildings, light industry and road transport being largely electric-powered.

The forecast mirrors a prediction by PetroChina. In a report released last month, the oil and gas producer expected that electricity would account for 62 per cent of energy consumption. It, too, said that hydrogen, green fuels and carbon-removal technologies such as carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) were important in cutting emissions.

But a projected 60 per cent share is lower than predictions from previous studies, some of which said electricity would account for about 80 per cent. A 2020 report by Tsinghua University suggested 70 per cent.

“The 2060 carbon-neutrality target is challenging, but it also creates opportunities – to position China as the global leader in low-carbon manufacturing,” said Mallika Ishwaran, chief economist at Shell International, at a webinar hosted by the company’s China business last Monday.

She added that China was “critical” to the world meeting the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate.

“With early and systematic action, China can deliver better environmental and social outcomes for its citizens while being a force for good in the global fight against climate change,” she said.

China is the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, contributing over 27 per cent of total global emissions – twice the share of the United States and more than three times that of the European Union. Chinese climate actions could have a make-or-break effect on the world achieving its climate goals.

About 70 per cent of China’s electricity comes from coal. Decarbonising the power system would require substantially increasing solar and wind power from 10 per cent of total power generation to 80 per cent by 2060, according to the Shell report.

Meanwhile, if electricity accounted for 60 per cent of China’s energy consumption, low-carbon fuels and carbon-removal technology would be required for the remaining 40 per cent in hard-to-electrify sectors, it said.

Sectors such as heavy-duty road transport, shipping, aviation and heavy industries including steel and chemicals, which rely on fossil fuels, would need to transition to new and lower-carbon energy sources such as hydrogen.

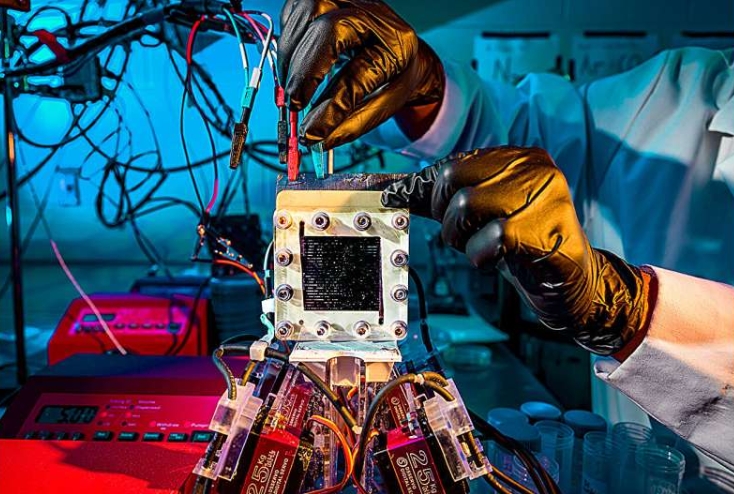

The Shell report said that hydrogen would account for 16 per cent of energy consumption by 2060, compared with negligible levels today, and more than 85 per cent of that would be “green hydrogen”, produced through electrolysis that is powered by renewable electricity.

In Britain this winter, production of green hydrogen was already cheaper than that of grey hydrogen (produced from fossil fuels), because of a spike in natural gas prices in Europe.

Energy institutions expect that green hydrogen can be cost-competitive with grey hydrogen by around 2030 in regions with abundant renewable resources.

China, the world’s largest producer of hydrogen, has prioritised it as an emerging industry under its five-year plan for 2021 to 2025.

The China Hydrogen Alliance, a government-supported industry group, has predicted that hydrogen will make up at least 5 per cent of China’s energy system by 2030.

Biofuels, including hydrogen, will be key for sectors – such as long-haul aviation and chemicals – that require higher-density liquid fuels. They are seen as one of the few low-carbon alternatives to liquid fuels in the near and medium future.

However, for China to reach net-zero emissions in less than 40 years, a shift to cleaner energy sources and energy efficiency will not be enough. It would also need to actively remove emissions, the Shell report said.

That will make CCUS an important part of the solution for China, which has significant geological potential for storing carbon: its storage capacity is second only to the US’.

China so far has more than 40 CCUS pilot projects with a total capacity of 3 million tonnes, but its capacity will need to increase more than 400 times in the next four decades to achieve the carbon-neutral goal.

Jiang Liping, deputy head of the State Grid Energy Research Institute, said that although the Shell report focused on hydrogen, biofuels and CCUS, there were great uncertainties about the development of these hot technologies.

“We need to pay attention to the future development of these technologies, because they relate to the construction of our entire energy system,” she told the webinar.

“If one, two or even three of these technologies are able to make rapid progress, we need to review the entire architecture of the power system.”