In the paper, Polysilicon Manufacturing forecast to 2030, the research firm outlines how fears that we may have passed the trough of solar costs during the pandemic will soon be replaced by record prices and a production capacity of nearly 1,000 GW.

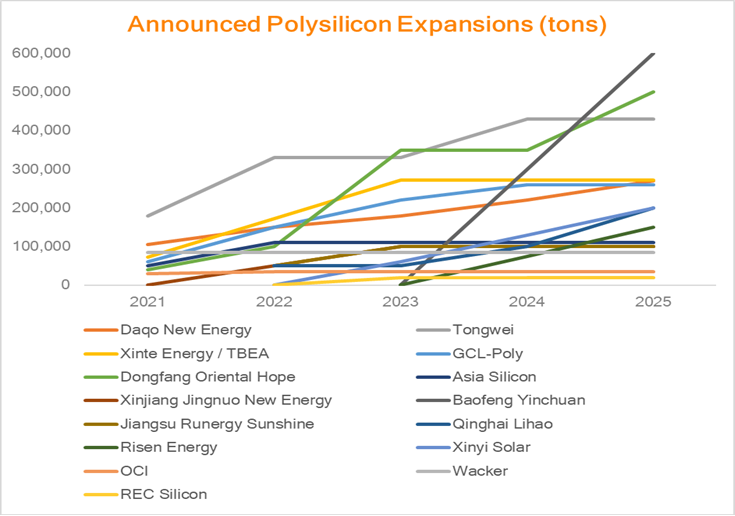

2022 will be the second and last year of the polysilicon shortage. While the economic rebound of 2021 saw demand exceed supply by 50 GW, with possibly an even bigger gap in 2022, pledges made by several dozen companies should see production capacity triple over the next three years, according to the study.

An expansion to nearly 4 million tons of solar-grade polysilicon production capacity will have been announced just in the last few weeks alone. Running at two-thirds capacity utilization would be enough to manufacture 900 GW of photovoltaics every year.

“The polysilicon shortage will continue to limit worldwide solar installations until mid-2023, in which year 250 GW of polysilicon solar will be commissioned. The price of polysilicon will take at least five years to return to the record low of 2020, but will then decline even further,” says Andries Wantenaar, solar analyst with Rethink Energy.

The shortage itself was caused by several factors. Low-cost Chinese production in the years preceding the pandemic pushed many companies out of business. To remain competitive, there was practically zero investment in new production capacity.

In 2020, with lockdowns crushing demand, the industry’s profits dropped to almost nothing, with polysilicon prices hitting record lows of $6 per kilogram.

So, after several further casualties through Covid-19, and as demand rebounded, the global polysilicon manufacturing capacity sat at just 621,000 tons in 2021 – with real supply a ways under 579,000, tons and cost concerns delaying some projects, this limited global installations to below 180 GW.

Rethink Energy estimates that, without the supply chain issues, underlying demand was between 205 GW and 220 GW.

With this shortage, prices have soared to around $40 per kilogram, with knock on impacts throughout the entire solar value chain. From March to the end of 2021 prices increased by 13% for modules and cells, 54% wafers, and 177% for solar-grade polysilicon.

For the remaining polysilicon companies, profits have been boosted as much as 300%, prompting massive expansion plans.

It takes around 24 months to build a polysilicon factory, however, and with the rapid surge in demand, manufacturers have so far been unable to respond, providing a hard cap on the amount of solar PV that can be installed worldwide – but only until mid-2023 when new factories will be operating in full swing.

The research outlines how the immense scale of the new manufacturing capacity, exceeding the surge in demand for photovoltaics, will mean that there will be a supply glut by 2025. As power prices once again start to fall, the result will be record low prices for polysilicon, consolidation, and several bankruptcies for those who fail to invest in reducing costs within the capital-intensive polysilicon segment. For solar as a whole, this readjustment will expose the massive LCOE declines of up to 12% across the sector that have been concealed by the economic turmoil of the past two years.

“Production capacity will more than quadruple this decade compared to the scale seen in 2020,” says Wantenaar, who points to the mass adoption of the fluidized bed reactor (FBR) granular production process. “China’s dominance of the industry will go from strength to strength, but India will build and shelter domestic production under protectionist policies, and the US may do likewise depending on the Biden Administration’s upcoming spending bills.”

The Western polysilicon makers, OCI and Wacker, have been given a new lease of life, having shut down under the record low prices of early 2020, they now have long-term orders to fill. It’s still expected that in time they will still transition to higher purities, making polysilicon for electronics instead of photovoltaics – so from 6N-9N purity to 9N-11N purity. But as with India, if the US stays the course with tariffs on Chinese goods, then it will be able to maintain and develop its own polysilicon industry as well. Recently Hanwha Q Cells, the Korean company exited the Polysilicon business, and may also make a comeback.

In the long term a few underlying economic factors will weaken China’s current advantages, the country will get wealthier which will push electricity prices up as will increased transmission links from the nation’s periphery to its heartlands, and the electricity usage per kilogram of polysilicon output will fall by maybe 25% over the coming decade.

By then it may not matter much if expansions have slowed as we expect.