In fact, according to a Goldman Sachs analyst, hydrogen could turn into a $1-trillion market in the future.

“If we want to go to net-zero we can’t do it just through renewable power,” Michele DellaVigna told CNBC earlier this week. “We need something that takes today’s role of natural gas, especially to manage seasonality and intermittency, and that is hydrogen.”

“And once we have it, I think we have a solution that could become, one day, at least 15% of the global energy markets which means it will be ... over a trillion-dollar market per annum,” DellaVigna also said. “That’s why I think we need to focus on hydrogen as the successor of natural gas in a net-zero world.”

As with most things, however, this is easier said than done. Green hydrogen has been attracting growing attention as it is considered the cleanest form of hydrogen production but green hydrogen has problems such as the fact that electricity for it comes from intermittent solar and wind, and that a lot of the energy used to produce hydrogen through electrolysis is lost, which means the efficiency of the process is limited, which in turn makes it more expensive.

As for blue hydrogen that includes carbon capture and storage, environmentalists have slammed it for being, effectively, greenwashing on the part of energy companies as carbon capture and storage technology has no real future, being ineffective and expensive. On top of that, most of the captured carbon dioxide is used for enhanced oil production, which also does not sit well with environmentalists.

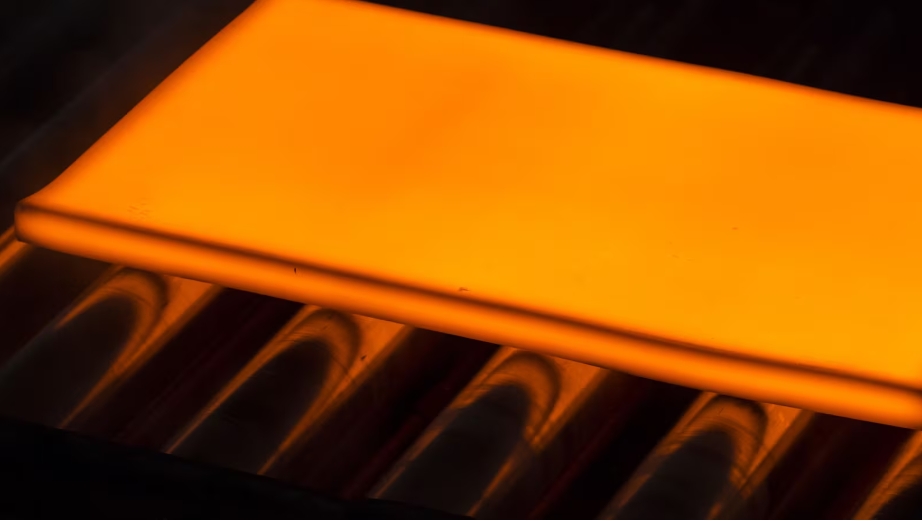

That said, hydrogen is, as Goldman’s DellaVigna called it, “a very powerful molecule”. Hydrogen is used in the treatment of metals; it is used in the production of fertilizers; and, of course, it can be used as fuel in fuel-cell cars. Hydrogen is also being blended already in the UK with natural gas and used for heating purposes.

Forecasts for the future of hydrogen and, more specifically, green hydrogen, the ultimate net-zero fuel, have been quite upbeat in the past couple of years. The main reason for this was falling costs associated with wind and solar energy as the technology continued to improve while raw material costs remained low.

Unfortunately for the upbeat forecasters, this is changing. The wind and solar industries are facing rising rather than falling costs as raw materials soar on the back of expectations for stronger demand and tight supply.

The Wall Street Journal reported earlier this month that wind turbine manufacturers are struggling with turning a profit because of costlier raw materials, logistical challenges, and uncertainty around subsidies, the last one in the United States. The report quoted a projection by Wood Mackenzie that anticipates a 10-percent increase in wind turbine prices over the next 12-18 months due to higher prices of steel, aluminum, copper, and carbon fiber.

Even so, companies are building electrolyzers in anticipation of more government support for hydrogen. Last year, for example, Shell built an electrolyzer in Germany to produce 1,300 tons of the element annually. The company admitted green hydrogen costs five times as much as fossil fuel-derived hydrogen but noted scale and efficiency improvements can bring costs down, as can additional government support.

France’s Engie and Emirati Masdar last year closed a $5-billion partnership to develop green hydrogen in the UAE. Per their plans, the two will develop projects with a total capacity of 2 GW by 2030, Engie said in December.

Then in January this year, Shell again announced the launch of a hydrogen project in China. The electrolyzer is one of the largest in the world and will take advantage of the abundant wind power capacity in the Hebei province of China.

The EU has plans to build electrolyzers with a total capacity of some 40 GW by 2030. Of this total, the EU wants to have 6 GW up and running within two years.

It seems obvious that the materialization of these plans would depend strongly on government incentives. Without them, the high costs of green hydrogen production would derail all the ambitious plans. The question, then, remains whether governments that are currently struggling with inflation rates not seen in decades, among other lingering effects of the pandemic, will have enough money to incentivize everything about the green transition they want to incentivize, including green hydrogen.