The US will not only fail to achieve President Joe Biden’s 2035 carbon-free electric grid goal but still be relying on coal and natural gas for 44% of power generation in 2050 – his Paris Agreement-aligned net-zero deadline, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Eliminating carbon from the grid is central to the administration’s long-term strategy to decarbonise industry and transportation, with all three comprising about 77% of US greenhouse gas emissions.

EIA, the statistics arm of the Department of Energy, in Annual Energy Outlook 2022 suggests that robust solar and wind generation capacity growth alone over the next three decades will be insufficient to substantially wean the US off fossil fuels.

“Wind and solar incentives, along with falling technology costs, support robust competition with natural gas for electricity generation, while the shares of coal and nuclear power decrease in the US electricity mix,” said the EIA.

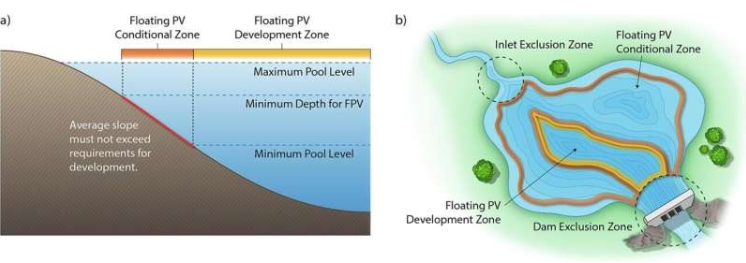

The agency's baseline reference case models that the national generation share of solar will increase from 4% in 2021 to 22% in 2050 and wind from 9% to 14%. Hydro and nuclear, the other major emissions-free sources, however, will see their shares decline from 6% and 19%, respectively, to 5% and 12%.

Despite a slew of plant closures this decade by utilities, coal in mid-century is expected to still be supplying 10% of US electric power, versus 23% last year, while natural gas will fuel 34% compared with 37%, according to the EIA.

The EIA noted that the huge forecast solar generation increase, while welcome for climate and environmental reasons as coal and natural gas-fired combined-cycle plants will operate less, is not problem-free.

By 2050, the large influx of solar capacity will cause a generation surplus in middle of the day, and this could ramp curtailments in three major US grids: California ISO (CAISO), Electric Reliability Council of Texas, and Midcontinent ISO (MISO).

This will place a premium on availability of battery storage to move excess solar energy during the daylight hours into the evening when demand is still relatively high.

In the report, EIA underscores the importance of continuing policies at the federal and state levels that provide economic incentives to drive significant investment in renewable resources for electricity generation. Among them is the production tax credit (PTC) for onshore wind which expired at the end of last year, creating uncertainty for that sector.

Biden’s Build Back Better bill, the centrepiece of his efforts to reassert US leadership on climate, is stalled in Congress. With the Ukraine crisis dominating Biden’s time and the attention of lawmakers, there is no timetable to advance legislation that would create or extend multi-year tax credits for solar, standalone storage, transmission, and wind.

EIA notes as the US adds more solar and wind capacity, both existing and new natural gas-fired generation will be displaced, and capacity factors for existing combined-cycle units will drop by nearly half from a peak of 60% in 2020. Natural gas will account for more than 40% of cumulative US capacity additions from 2020 to 2050.

The agency projects that about half of natural gas capacity additions through 2050 will be low-utilisation combustion turbines, which are economically attractive when mostly used to provide infrequent peaking capacity.

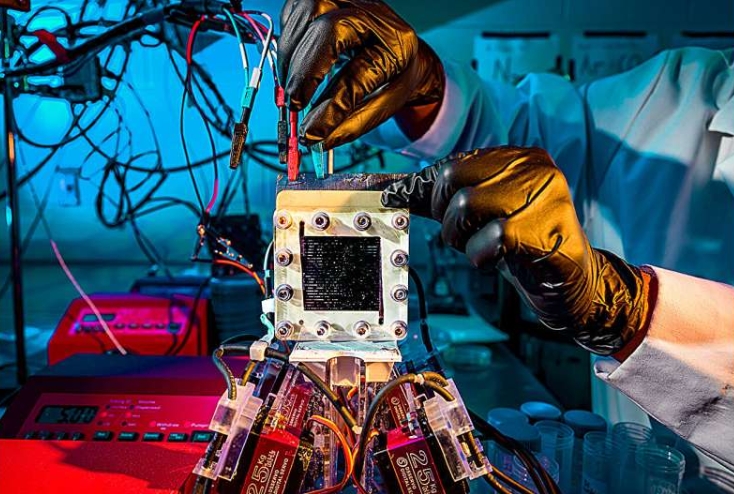

“Energy storage systems, such as standalone batteries or solar-battery hybrid systems, will compete with natural gas-fired turbines as sources of back-up capacity for non-dispatchable renewable energy sources,” according to Annual Energy Outlook 2022.

Even so, US consumption of natural gas will continue to grow over the next three decades with prices remaining low compared with historical levels.

As natural gas-fired generation sets power prices in bulk electricity markets most of the time and those prices will remain relatively low over the next three decades, this will continue to affect the profitability of coal and nuclear units, which have high fixed costs. The result will be further closings in the years ahead, according to EIA.

Some older nuclear plants are receiving federal and state subsidies to remain open but there is no long-range plan to continue those payments to retain their baseload power.