The Traton Group sees an analysis by the Fraunhofer Institute as confirming its strategy with its focus on battery-electric drives. According to the study, electric drives will also dominate the heavy-duty sector, and fuel cells will remain a niche application. On the other hand, Daimler Truck continues to rely consistently on both technologies.

Traton surmises that, in most regions and commercial vehicle applications, the battery-electric drive is superior to the fuel cell. This also applies to heavy long-distance transport. The results of the study are well received by the company. “We are pleased with the clarity of the analysis result, even though it does not surprise us. It once again confirms the Traton Group’s strategy of focusing on battery-electric powertrains for our commercial vehicles,” says Catharina Modahl-Nilsson, Chief Technical Officer at Traton.

“The battery-electric long-haul trucks are coming, the technology is there, and the networks will follow suit,” Modahl-Nilsson continues, adding, “What we need now is political support to quickly achieve massive CO2 savings with this technology.” Therefore, developing an efficient charging network for electric trucks must be quickly pushed ahead with government support.

A study published last week by Ifeu came to a very similar conclusion as the Fraunhofer analysis. According to this study, battery-electric and trolley trucks will dominate in 2030 due to their cost advantages. Fuel cell trucks will not keep up with their battery electric and overhead catenary counterparts with hydrogen from Germany. “The use of fuel cell trucks, therefore, represents a bet on the future availability of cheap and fully renewable imported hydrogen in the medium term,” the study concludes.

Daimler Truck sticks to hydrogen

But is the matter really so straightforward? At Daimler headquarters in Stuttgart, the latest figures and studies are obviously assessed differently than at Traton in Munich: Daimler Truck positions itself quite differently when it comes to the drive of the CO2-neutral future. In its own press release, the commercial vehicle manufacturer reaffirms its current dual strategy for the electrification of its portfolio: battery and hydrogen-based drives. The reason given by Daimler Truck is the many different applications and tasks of trucks. For flexible and demanding applications, especially in the heavy-duty long-haul segment, hydrogen-based powertrains could be the better solution, the German automotive giant says in a statement. Daimler Truck makes no reference to the Fraunhofer study.

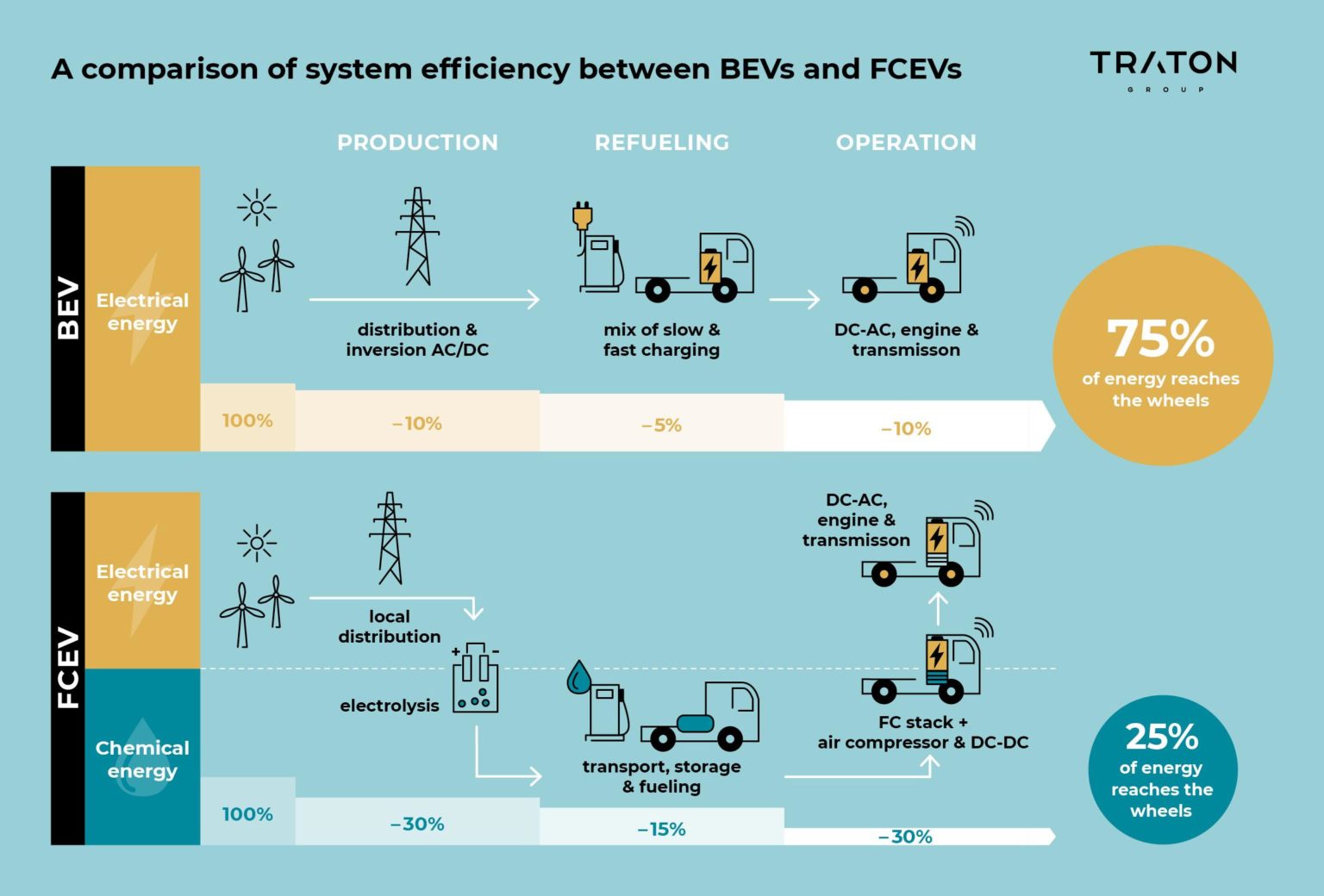

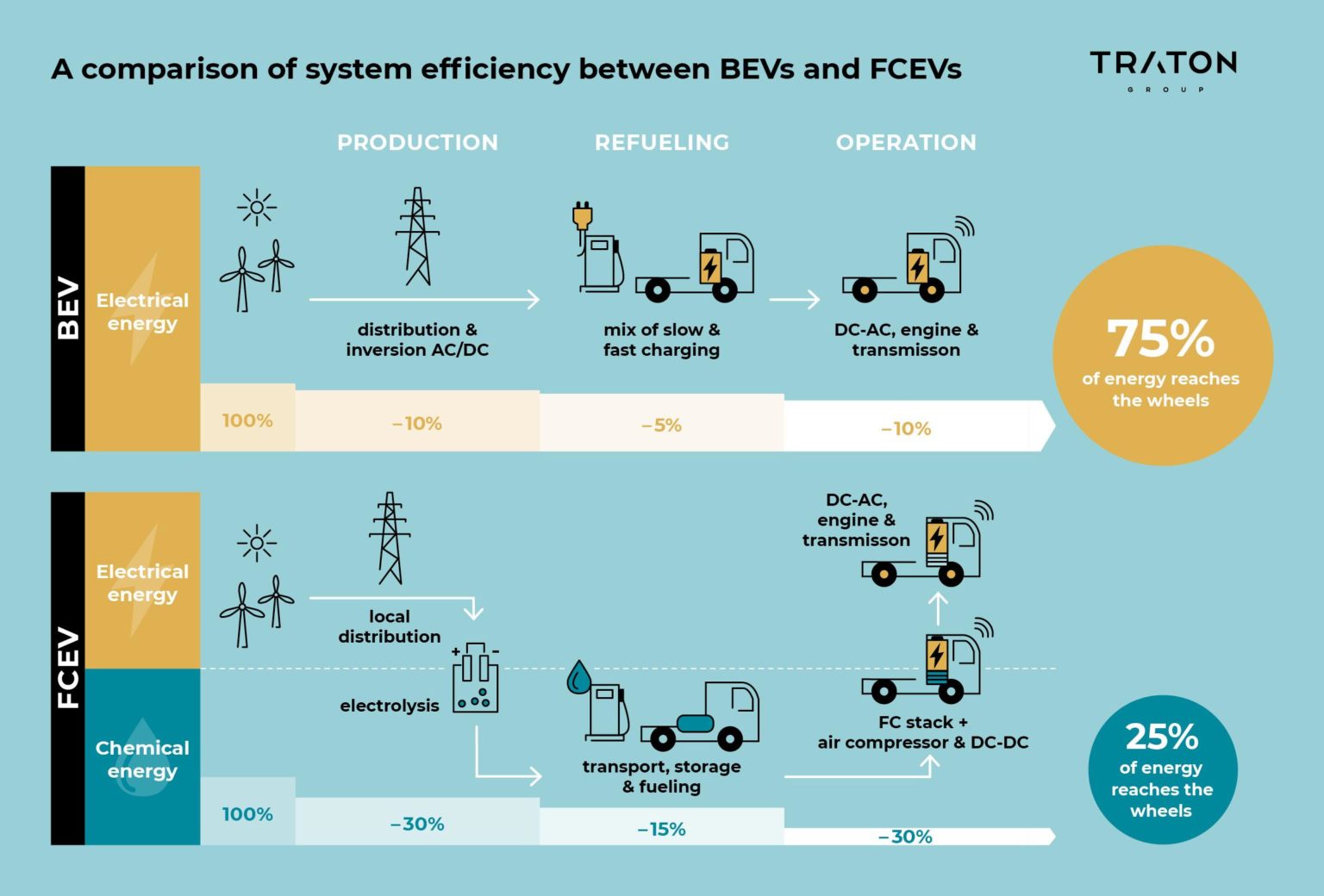

“There will always be discussions that only deal with individual partial aspects of different alternative drive forms, such as energy efficiency. This is indeed higher for battery-electric than for hydrogen-based drive systems, but the bigger picture is forgotten,” says Andreas Gorbach, Member of the Board of Management of Daimler Truck AG and Head of Truck Technology.

“In addition to efficiency, the availability of an appropriate infrastructure and sufficient green energy is crucial for a successful conversion to zero-emission technologies,” continues Gorbach. And a rapid and cost-optimised coverage of this energy demand is only possible with both technologies; he is convinced. “Hardly any country in the world will be able to supply itself with green energy alone at competitive prices in the future. Consequently, there will have to be a global trade in a CO2-neutral energy carrier,” he adds. Green hydrogen will play a central role in this, he says.

Daimler Truck refers to political efforts around hydrogen

Daimler Truck assumes that green hydrogen will be traded at “very attractive prices” in the future. Other reasons for the use of hydrogen are advantages in costs and technical feasibility of the infrastructure and greater ranges, flexibility and shorter refuelling times for customers. When it comes to the question of the best transport solution, energy efficiency is “an important, but by no means sufficient criterion”.

Gorbach points to the fact that more than 40 governments worldwide have launched comprehensive hydrogen action plans and to the announcements of many globally active companies. According to him, experts expect hundreds of billions of euros to be invested in hydrogen production, transport and infrastructure before the end of this decade.

The Fraunhofer analysis with the title: ‘Hydrogen unlikely to play a major role in road transport, even for heavy trucks’, which was firmly pushed by Traton, was published in the journal Nature Electronics. A report on this was published by the platform rechargenews.com. It says: Hydrogen will not play a major role in road transport, even for heavy trucks. Fuel cells have lost their former advantages of range and fast charging and will probably not compete with battery EVs.

“Hydrogen will play an important role in industry, shipping and synthetic aviation fuels,” Patrick Plötz, coordinator of the Energy Economics Division at the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research (ISI) in Germany, is quoted as saying. “But for road transport, I don’t think we can wait for hydrogen technology to catch up, and our focus should now be on battery-electric vehicles for both passenger and freight transport.”

The study looks separately at passenger cars and trucks. With regard to passenger cars, Plötz says, “the window of opportunity for establishing a relevant market share for hydrogen cars is as good as closed”. At this point, he makes a comparison according to which around 25,000 hydrogen fuel cell cars were on the roads at the beginning of last year, and around 540 H2 filling stations were in operation worldwide. This compares to an expected 15 million battery-electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles at the beginning of 2022, more than 350 models worldwide. Although most e-vehicles would be charged at home, Plötz said there would also be about 1.3 million public charging points in 2020, a quarter of them fast chargers with at least 22 kW; in Europe, he said, more than 1,000 public chargers with up to 300 kW were available.

For Plötz, the latest technological developments mean that FCEVs have lost their raison d’être. “When battery-electric vehicles had a limited range of fewer than 150 kilometres and took several hours to recharge, there was an important and large market segment for fuel cell vehicles: long-distance trips,” says Plötz, referring to the higher energy density of compressed hydrogen and the possibility of quick refuelling. “However, battery-electric vehicles now offer a real-world range of about 400 kilometres, and the latest generation uses 800 V batteries that can be recharged in about 15 minutes for a range of 200 kilometres.”

Fallacy of sunk costs?

Plötz is also critical of current financial expenditures in hydrogen cars. “Many of the current investments in hydrogen cars seem to follow the sunk cost fallacy: We’ve already spent so much on this technology, we shouldn’t give up now.” Given the economies of scale in batteries, further expected cost reductions and performance improvements in electric vehicles, as well as charging infrastructure, it is highly unlikely that fuel cell cars will be competitive, he concludes.

Plötz’s view of the truck sector is not much different. The hydrogen-powered truck sector is also less advanced than the battery-powered sector. Plötz states that about 30,000 electric trucks are in stock worldwide, most of them in China. In addition, more than 150 battery-electric truck models for medium and heavy goods transport have already been announced. On the other hand, fuel cell-electric trucks are only being operated in test trials and are not yet commercially available. Plötz considers the target issued by several truck manufacturers, fuel cell and infrastructure providers of having 100,000 fuel cell trucks on European roads by 2030 to be unlikely.

According to Plötz, the current challenge for battery-electric vehicles lies in long-distance logistical operations with an average of 100,000 kilometres per year and the transport of very heavy goods. However, he sees an opportunity in the 45-minute break for truck driving that is mandatory in Europe – provided the appropriate charging infrastructure exists. “Within 4.5 hours, a heavy truck could cover up to 400 kilometres, so practical ranges of about 450 kilometres would be sufficient if powerful, fast chargers for battery-electric trucks were widely available,” says Plötz.

MCS standard to be available in 2023

Charging 400 kilometres in 45 minutes would mean about 800 kW average charging power for a heavy truck. The current fast-charging standard allows up to 350 kW. Still, a new standard for megawatt charging systems is currently being developed to allow a charging power of over two MW and should be available by 2023.

Charging 400 kilometres in 45 minutes means about 800 kW average charging power for a heavy truck. The current fast-charging standard allows up to 350 kW, but a new standard for megawatt charging systems is currently being developed to allow a charging power of more than two MW and should be available by 2023.

Plötz also points to studies showing that the total cost of ownership for trucks with fuel cells is higher than for battery-powered models with megawatt charging stations. “For trucks, operating costs are more important than for cars, so the use case for fuel cell electric trucks is even smaller.”

“If truck manufacturers do not start mass production of fuel cell trucks soon to reduce costs, such vehicles will never become established in low-carbon road transport,” concludes Plötz. “Policymakers and industry need to decide quickly whether the fuel cell electric truck niche is large enough to support the further development of hydrogen technology, or whether it is time to cut their losses and focus their efforts elsewhere.”

Traton plans E share of 50 per cent by 2030

Traton believes the high cost-effectiveness of electric trucks in long-distance transport is the most important lever for a zero-emission future. “We expect that up to 50 per cent of our new sales in long-distance transport could be battery-electric by 2030, provided the charging infrastructure is in place,” says Andreas Kammel, who is responsible for the strategy on alternative drives and autonomous driving at Traton. “This should not fail because of the resilience of the power grids – our trucks charge mainly at midday and at night when demand and prices are particularly low.”

Daimler Truck wants to offer only new vehicles in its global core markets by 2039 that are CO2-neutral in driving mode. “In this way, we will offer our customers a tailor-made zero-emission solution for every transport task. With the enormous backing of numerous partners from industry and politics, we will successfully bring both technologies to the road,” says Gorbach.

Daimler Truck is working with Linde to develop the next generation of liquid hydrogen refuelling technology for fuel cell trucks. An agreement was signed at the end of 2020. The partners want to make hydrogen refuelling as easy and practical as possible. In hydrogen refuelling station infrastructure along major transport axes in Europe, Daimler Truck plans to work with Shell, BP and TotalEnergies. In addition, Daimler Truck, Iveco, Linde, OMV, Shell, TotalEnergies and the Volvo Group want to jointly help hydrogen trucks achieve a breakthrough throughout Europe as part of their H2Accelerate (H2A) consortium. In 2021, the company founded the joint venture cellcentric with the Volvo Group, which manufactures fuel cell systems.