Delving into the world’s largest carbon capture project, ExxonMobil’s Shute Creek CCUS facility, reveals a highly questionable technology.

• ExxonMobil’s Shute Creek Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) facility is designed to remove CO2 from gas to produce marketable methane.

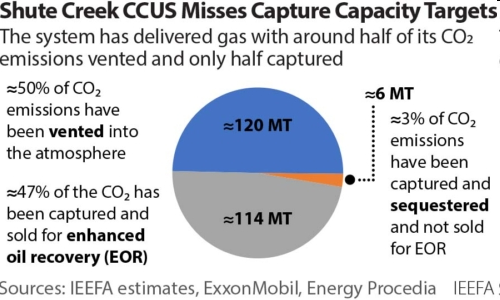

• About half of that CO2 has been vented into the atmosphere over the facility’s lifetime.

• Of the other half of the CO2 that has been captured, nearly all has been sold to oil companies that use it to recover more oil from depleted wells.

• Only about 3% of the captured CO2 has been sequestered underground.

• When the price of oil goes down, the facility sells less and vents more of its CO2.

ExxonMobil’s Shute Creek Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) facility located in Wyoming, U.S., has been operating since 1986.

Over its lifetime, facility executives report it has captured about 120 million tonnes (MT) of carbon dioxide (CO2), which is around 34% less than its designed CO2 capture capacity, based on publicly available data and company disclosures according to IEEFA’s findings. An estimated 66 MT of CO2 has been emitted to the atmosphere during the facility’s lifetime, in addition to the inevitable vent of CO2 from the gas processing facility (≈ 54 MT).

Despite huge investment globally over the last 50 years, and the pace of recent carbon capture build-up in the fossil fuel industry, the technology is still found wanting — as is the motivation of companies using it.

Around 95% of Shute Creek’s captured CO2 (≈ 114 MT) has been sold to oil companies for enhanced oil recovery — a process in which CO2 is pumped into depleted wells to recover more oil. The recovered oil is then burned, emitting CO2 to the atmosphere.

Treating CO2 as a marketable by-product

When the Shute Creek project was designed in the early 1980s emission reduction was not the primary goal. In fact, Shute Creek used CCUS to make its gas marketable.

In gas processing plants, CO2 has to be removed from extracted raw gas to get marketable methane (“natural gas”). Removing CO2 increases the heating value of gas and prevents technical problems during the transportation, distribution or liquefaction phases.

Removing CO2 in Shute Creek’s case was expensive because the field had exceptionally high CO2 content. The viability of the project relied on treating CO2 as a marketable by-product which could be sold to oil companies for enhanced oil recovery.

Very sensitive to oil price volatility

CCUS improved profitability for both ExxonMobil’s Shute Creek project and the oil companies who bought the CO2 to produce more oil.

But the model is very sensitive to the oil price volatility. When oil prices are high, oil companies have incentive to buy it for enhanced oil recovery. But when oil prices are low, the demand for captured CO2 declines, so the greenhouse gas is then vented into the atmosphere.

“Sell or Vent” doesn’t reduce emissions

This “Sell or Vent” model does not reduce emissions.

Indeed, the Shute Creek project has rarely met its maximum capture capacity during its 35-year lifetime. Around half of Shute Creek’s total CO2 emissions have been vented over its lifetime. Only around 3% has been sequestered underground and about 47% has been sold for enhanced oil recovery. In short, the facility hasn’t captured the volume of CO2 it was designed for, for economic, rather than technical reasons.

CCUS projects using a “Sell or Vent” business model, are by far the largest application of carbon capture technologies today, where carbon is utilised for enhanced oil recovery before being partly stored in depleted oil wells.

Despite the fact that this system increases fossil fuel production, the oil and gas industry has deftly portrayed CCUS as climate positive.

In fact, the model is also on shaky economic footing. To stay profitable, CCUS coupled with enhanced oil recovery requires a high oil price, and in many cases, subsidies.

Perversely, some governments are subsidising production from high-CO2 gas and oil fields and enabling more oil and gas production through enhanced oil recovery — and framing those subsidies as “climate-friendly.”

Currently, large government subsidies for CCUS are proposed in the U.S. and are being granted in Australia through its Emissions Reduction Fund.

Subsidies are wasted on these CCUS and CCS projects

According to the Global CCS Institute, more than 70% of all carbon capture projects globally are CCUS and used for enhanced oil recovery.

Another model, Carbon Capture and Storage, dedicated to the capture and (underground) storage of CO2 without any further use, makes up less than 30% of the total in operation worldwide. CSS has also been promoted as a potential solution to reduce emissions.

However, CCS projects also face technical difficulties and their economic viability is uncertain, as evidenced by the failed Chevron Gorgon CCS project — the largest CCS project in the world with dedicated geological storage based in Western Australia.

Overall, the majority of commissioned carbon capture projects globally have not attained the levels of capture/storage they aim to achieve.

At best, carbon capture appears unrealistic as a climate solution. And the CCUS model should mainly be seen as a subsidy harvesting scheme to prolong the life of the oil and gas industry, not an emission reduction investment.