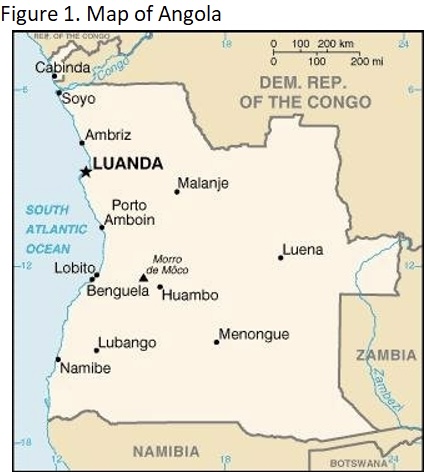

A vineyard agri-PV demonstration project in France. Agricultural applications are attracting generous subsidies in places like Italy. Source: Sun’Agri

A vineyard agri-PV demonstration project in France. Agricultural applications are attracting generous subsidies in places like Italy. Source: Sun’Agri

The dire need for European countries to reduce gas consumption, combined with available EU funds for the energy transition, creates political incentives to provide subsidies for renewable energy projects, including solar and battery energy storage. Governments are introducing schemes that may accelerate the development of expensive applications and emerging technologies such as agrivoltaics.

Italy, which recently received the first payment of €21 billion ($23.53 billion) from the Next Generation EU fund to propel recovery after the pandemic, is an example of lavish public support. The country is currently working on two programs for the agricultural sector. The first targets rooftop PV installations for energy-intensive farms at the 375 MW Agrisolar Park (“Parco Agrisolare” in Italian), and the second is still being negotiated.

“The Italian government will make €1.5 billion available for just 375 MW of installations for the Agrisolar Park, bringing the cost of these subsidized solar systems, including batteries, roofing, and vehicle charging stations, to almost €4,000/kW. On the market, a rooftop installation with the same characteristics costs up to three times less,” said Mauro Moroni, energy transition ambassador of Kiwa Italia.

According to Moroni, the regime recalls the tax deductions linked to the 110% tax deduction for energy efficiency and small systems for the residential sector, which have “created distortions on domestic systems in the last two years, raising the cost of installations.” He adds that similar programs could cause some already-taken decisions to invest private funds to be delayed, while creating a harmful image for the sector.

Agri-PV subsidies

The direct beneficiaries of the Italian agri-PV program underline that, while the subsidies are significant, they are also in line with their mission. They explain that the Agrisolar Park is not merely meant to increase solar capacity, as proven by the fact that the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (Mipaaf) is responsible for the scheme.

“From an external perspective, it may seem a speculative measure, but we are talking about farms and not houses. We are talking about a business support measure for the coming years,” said Francesco Mastrandrea, president of Italy’s Young Farmers’ Confederation.

Mastrandrea told pv magazine that the scheme creates the conditions for more innovative energy-intensive farms and cowsheds. He argues that farmers would not install PV on asbestos-laden rooftops, given the removal and disposal expenses for the now-banned material.

“Italian agriculture is thousands of years old and has infrastructures that are no longer used. The functionality of this infrastructure should be maximized,” said Mastrandrea.

To improve this first scheme, Mastrandrea calls for removing the self-consumption condition in the scheme. “I would favor feeding electricity into the grid because many sheds could host PV installations. Support for agriculture could increase food and energy security for end energy consumers in the surrounding areas,” he said. The decree on the Agrisolar Park is still under discussion in Brussels, and Mipaaf is waiting for feedback.

An inter-ministerial commission is currently working on the second program for agri-PV to be launched by the Ministry of Ecological Transition. Farmers, the leading association of the power sector (Elettricità Futura), and other stakeholders, are negotiating.

The farmers’ association adds that Italy could meet 60% to 70% of its energy needs by installing PV systems on 0.2% of its usable agricultural land. “If we look at the number of abandoned lands each year, we can see that the energy element comes at the right time,” concluded Mastrandrea.

Past scars

High subsidies have been relatively common in the European PV sector, not only in Italy. The example of the Czech Republic demonstrates how generous schemes have negative repercussions, possibly lasting even for decades.

“We had a solar boom in 2009-10, when 2 GW were installed with feed-in tariffs. Two thousand power plants were built, which cost more than €1 billion a year,” said Jan Krčmář, chairman of the Czech Solar Association. “In the government’s view, [it] is pretty much a feed-in tariff. And they had a bad experience with that once. They don’t want long-term operational subsidies anymore.”

Krčmář is explaining to policymakers that the mistakes made with previous auctions are now avoidable. Still, the Czech government designed a “peculiar” investment subsidy system for utility-scale ground-mounted power plants, financed by the Modernization Fund through the revenues from CO2 certificates.

“The solar park, unlimited [by] power [capacity], can apply for up to €250,000 per MW as one-off subsidies. You build the power plant and sell electricity via PPAs or the market. Once you connect, you receive a subsidy,” explained Krčmář.

“The state subsidy is an investment subsidy. When the program was designed a year ago, electricity prices were low … now with high energy prices, projects are very lucrative.” Krčmář continued, adding that most investors designed the projects without factoring in the subsidies because they would not get them automatically. “If they get them, great; otherwise, they would go ahead anyhow.”

The Czech subsidies also don’t require the projects to receive the building and zoning permits, meaning the state might support projects that local authorities might then reject.

Krčmář said that governments should promote auctions instead, as part of a broader support mechanism. “Smaller investors would also enter auctions if that meant selling the electricity to €70/MWh if they were given advantages like building on agricultural land and quick permitting procedures. Investment subsidies don’t normally drive down electricity prices.”

Romanian costs

Romania recently issued a new state aid support scheme for wind and solar generation as part of the recovery and resilience plan.

“The total budget is €457 million, and the application window closes at the end of May. The state aid must not exceed €425,000/MWp for solar projects of installed capacities above 1 MW,” explained Andrei Covatariu, co-founder of ECERA, a network of sustainability practitioners.

The Romanian expert argues to resort to the current tender design, which involves a guaranteed strike price determined by tenders with decreased bidding, and subsequent auctions, changing as a function of new market conditions.

“By doing so, we will benefit from any cost reduction given by improvements in manufacturing and maybe by scaling up some manufacturing processes in Europe. Moreover, Romania benefits from the Modernization Fund under the ETS [Emission Trading Scheme] and a generous allocation via Next Generation EU, so this should enable development with minimal impact on consumer bills in the short and medium-term,” Covatariu told pv magazine.

Covatariu expects that the cost of renewable capacities will increase in the coming years due to an increase in global prices of energy and rare earth metals. “Moreover, as manufacturers will have a limited production capacity, they might increase prices to differentiate between buyers. For this reason, compared to tenders held before 2022, a need for increased subsidies is to be expected,” ECERA’s co-founder added.

This price increase might also lead to lower competition in future tenders, with more prominent companies exercising their negotiating power to get better prices for the same components, Covatariu argues. He says that foreseeable conditions are needed to avoid further stifling competition.

“At the beginning of 2010, Romania had a generous investment scheme. It was the beginning of the green investment, so there were not too many best practices and references to learn from. The scheme had no different investment periods, and, practically, it was not considering the learning cost for different technologies. Consequently, it immediately translated into a challenge for some customers, especially the industrial energy-intensive ones. For these reasons, the authorities had to redesign the support scheme while it was in place, which transformed the country into a rather unfriendly destination for new energy investments.”

Subsidy design

Experts suggest that PV subsidies should be a function of inflation, the attractiveness of the local market, which strongly depends on permitting process, and, more generally, the coherence of political messaging. At the same time, subsidies could also accommodate geopolitical priorities. Finally, technological developments and the complexity of different installations should be central to the design.

Going back to the Italian agri-PV example, Moroni says that subsidies are not the way forward in most cases, also with the current conditions. “The Italian EPC supply chain may have to be rebuilt, the cost of materials has risen, and there is a crisis in the availability of chips on the inverter side. So, incentives make some sense, but the government needs to progressively lower the incentives, and conduct competitive auctions by facilitating the authorization part for large plants while maintaining a reasonable tax deduction for small plants to the limit,” said Moroni.

Others suggest governments should prioritize less established PV structures, including installations with a vertical orientation.

“As things stand now, you do need subsidies for innovative technologies that would not be able to be deployed otherwise, like floating solar. In these cases, subsidies allow to decrease the risk of the investment risk,” said Carlotta Piantieri, associate at Aurora Energy Research. “Ground-mounted solar economics are already solid at market prices and with PPA contracts. No need for subsidies,” concludes Piantieri.