Vast gas reserves across Africa have been ignored for years. This may now change as the world scrambles for alternatives to Russian energy.

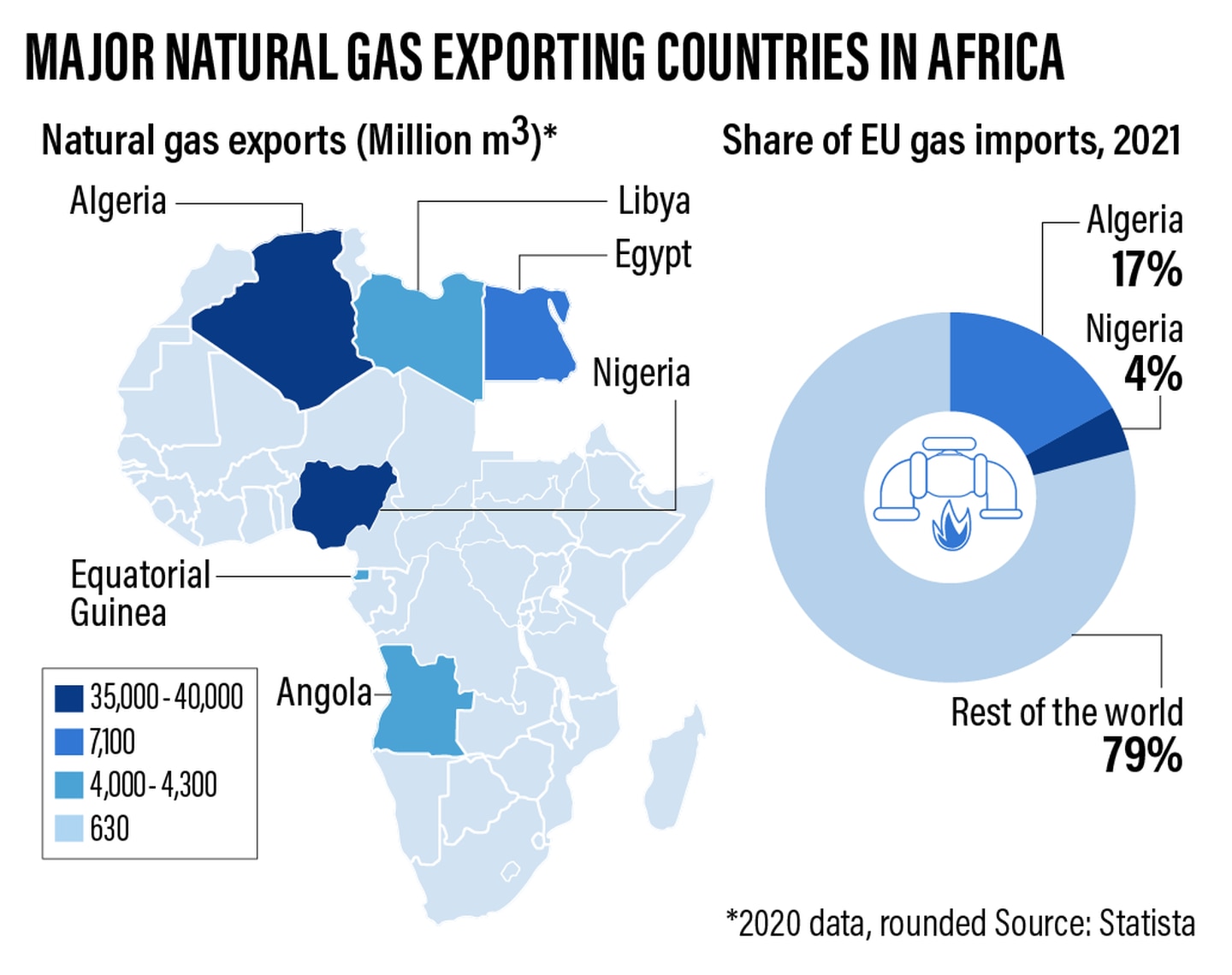

Currently, Africa meets only 15 per cent of the world’s gas demand — and most of this is from just one country, Algeria. Yet the continent has plenty of gas, particularly south of the Sahara. Development has been lacking, however, as poor infrastructure, civil conflict and other problems have kept energy companies away.

“One of the biggest challenges is sustainability of supply, because most of it comes from volatile areas where there is war,” says Linda Mabhena-Olagunju, chief executive of Johannesburg-based DLO Energy Resource Group.

“We have seen this in the Niger Delta, as well as more recently in northern Mozambique where Total had to pull out most of its staff due to ongoing terrorism.”

The European conflict may now encourage risk-averse energy investors as they seek new gas supplies.

Nigeria, for instance, has an estimated 200 trillion cubic feet of gas, enough to make it a potential supplier to gas-dependent regions such as Europe.

Until now, the country’s oil producers have treated gas as a nuisance by-product. However, the Russia-Ukraine war has inspired Nigerian authorities to dust off a longstanding plan to build a pipeline to Europe — a $25 billion project across 13 countries and the Mediterranean Sea.

For years, the plan had been viewed as pie in the sky, but under current circumstances, it is being taken seriously … so much so that Opec has contributed nearly $15m to carry out a feasibility study.

“We are seeing an increase in drilling in Nigeria, and Total is bringing its staff back to Mozambique,” says Ms Mabhena-Olagunju.

Still, many remain sceptical that Africa is close to meaningfully joining the global gas production network.

Historical problems continue to plague the continent’s potential energy producers, says Corti Paul Lakuma, a research fellow in the macroeconomics department at London’s Economic Policy Research Centre.

“Geopolitical wrangling, lack of infrastructure and willingness to put in place what’s needed will hold Africa back,” he says.

“Yes, there’s an opportunity for Africa to supply [to] Europe, but not in the next five years. For Africa to supply Europe sufficiently, I’d give it 20 years — it’s not to be considered in the short term.”

Some even suggest that the energy landscape should pivot away from carbon fuels altogether and use another gas — hydrogen.

“Europe is looking at hydrogen with renewed urgency, with projects in 12 EU countries, and more on the way,” says Demetrios Papathanasiou, global director for Energy and Extractives Global Practice at the World Bank.

Hydrogen can be used as a feedstock for fuel cells, which can power motor vehicles, houses and many other electricity-intensive applications.

While most is sourced by extracting it from natural gas, hydrogen molecules can also be split from water, a process that creates no carbon emissions. The latter process called electrolysis can be powered by wind and solar energy.

“Africa is really at the table, given its large wind and solar power endowment,” says Mr Papathanasiou. “Now is a good time to consider investment in fresh technology that would help the world decarbonise, and also allow Africa to get in on this technology development early.”

In the meantime, countries are rushing to develop their gas deposits as the clock ticks on the fossil fuels. A recent discovery shows that as much as 1.5 trillion cubic feet of gas lies off the west coast of South Africa and Namibia, according to data by TotalEnergies and Shell.

“The oil and gas resources north of the Orange River offshore border with Namibia will be developed, and the same geology is likely south of the border in South Africa,” says Anton Eberhard, energy policy specialist and adviser to the state.

“As petroleum majors lose oil and gas resources and production in Russia, they will replace them with new fields, including in Africa.”