The Steenbras Dam in Western Cape, South Africa. (Credit: Hansueli Krapf/Wikimedia Commons)

An energy system focused on renewable energy can help resolve many of the social, economic, health and environmental challenges of Africa, according to new analysis published by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) in collaboration with the African Development Bank (AfDB).

Such an energy transition is not only feasible, the two organisations state, but essential for a climate-safe future in which sustainable development prerogatives are met.

The report, Renewable Energy Market Analysis: Africa and its Regions, shows how an integrated policy framework built around the energy transition could bring a wave of new sustainable energy investment to Africa, growing the region’s economy by 6.4% by 2050 and creating further gains in human welfare in each region of the continent.

“Africa’s governments and people are too often asked to rely on unsustainable fossil fuels to power their development when renewable energy and energy efficiency solutions offer economically attractive and socially beneficial alternatives,” said Francesco La Camera, Director-General of IRENA. “The transition offers a unique opportunity for Africa to meet its development imperatives. Through tailored policy packages, African countries can harness their strengths and resources to overcome long-established structural dependencies.”

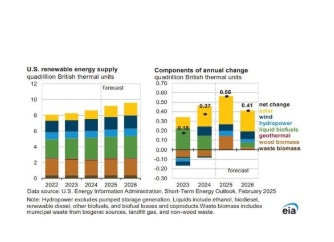

The report shows that African renewable energy deployment has grown in recent years. Over the past decade of 2010-20, renewables-based generation capacity on the continent grew by 7% – largely driven by utility-scale hydropower and solar projects. And although the region is prospering significantly from such development which has greatly improved energy access, welfare and environmental benefits for people, a large part of Africa has so far been left out of the energy transition:

• Only 2% of global investments in renewable energy in the last two decades was made in Africa, with significant regional disparities

• Less than 3% of global renewables jobs are in Africa

• In Sub-Saharan Africa, electrification rate was static at 46% in 2019 with 906 million people still lacking access to clean cooking fuels and technologies

“Africa is endowed with abundant renewable energy sources, upon which it can sustainably base its ambitious socio-economic development,” said Dr Kevin Kariuki, African Development Bank, Vice President for Power, Energy, Climate and Green Growth.

At 34GW capacity by the end of 2020, hydropower is the largest source of renewables-based electricity in Africa, with a sizeable unexploited potential. However, as Kariuki points out, developing such resources “requires strong political commitment, a just and equitable energy transition framework, and massive investments”. He added that the African Development Bank is committed to supporting the continent’s energy transition, by facilitating increased private sector investments through its expanding range of green finance instruments, including the Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa.

“Enabling African countries, which have contributed little to historic greenhouse gas emissions, to develop, while recognising the need to address the climate emergency is imperative,” IRENA Director-General La Camera commented.

Cameroon commitment

CDC Group, the UK’s development finance institution, announced that it exceeded its 2020 commitment to invest £2 billion in Africa over the past two years. A £75.5 million commitment to the Nachtigal Hydro Power in Cameroon is among the major infrastructure investments it has recently made.

The company, which is soon to be renamed British International Investment (BII), said it had invested almost £2.2 billion in African businesses in 2020 and 2021, despite the unprecedented upheaval caused by the Covid pandemic.

Nick O’Donohoe, Chief Executive of CDC/BII, said: “I am delighted that we exceeded the ambitious target we set at the Africa Investment Summit held in London in 2020. This was during a period when CDC rapidly pivoted to support our portfolio and mitigate the economic fallout of the pandemic in the countries in which we invest. The role of DFIs such as CDC was vital in supporting vulnerable countries that did not have the financial reserves to protect their economies.”

Located on the Sanaga River near the Nachtigal Falls, the new Nachtigal project will cover 30% of Cameroon’s electricity demand, amounting to an annual output of nearly 3TWh. The project was initially expected to be completed by the end of 2023, but due to delays caused by the coronavirus pandemic, Nachtigal Hydro Power Company has now been tasked with starting operations of the first machine in July 2023, with final commissioning in July 2024.

Invest in water security

The climate crisis caused massive disruption to Africa’s human and economic potential in 2021 and will continue to do so until significant investment is made in the country’s adaptation capacity, says Alex Simalabwi, Executive Secretary of the Global Water Partnership (GWP) in Africa. And, according to the African Development Bank, the continent currently faces an annual water investment gap of US$49-54 billion: approximately equal to the 2021 GDP of the Democratic Republic of Congo or Cameroon.

The GWP, a global action network focused on the sustainable management of water resources, warns that longer and more severe droughts could become the norm not only in Africa but also in other parts of the world. Over the past 20 years, droughts have already increased by 29%. Over one in four people live in countries affected by water stress, and by 2050 more than five billion people might suffer from water scarcity, threatening 45% of the world’s economy.

Possibly most notable among the water security crises of 2021, Simalabwi says, is what has been called the first “climate change induced famine” where the food crisis in Madagascar left 1.3million people in need of humanitarian aid. Last year drought also ravaged the Horn of Africa, an historically semi-arid region where 70% of the population live in areas that are prone to food shortages and resulted in deterioration of crop fields and loss of livestock in Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia. Abnormal dryness also characterised the Angolan 2020/2021 rainy season and pushed people to migrate out of the country in search of water, food, medical services, and economic opportunity.

Water sits at the centre of the climate change devastation of Africa, Simalabwi says, because it is felt through the impact on already vulnerable water resources. In addition, according to the IPCC, the region’s rate of surface temperature increase has generally been faster than the global average, and the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events are projected to increase in almost all sub-regions.

Water crises can only be eased if water is treated as a top priority by international climate policy makers and if countries manage their water resources in an integrated way. GWP says that there is still a lack of political will to commit enough resources that will result in better, more efficient, and more sustainable water resources management, and calls for investment in African water security to be made a priority in 2022.

However, the Glasgow Climate Pact, signed at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, does offer some hope that the situation could improve for Africa: a region which contributes only 4% of global emissions yet has the greatest risk to climate hazards. The Pact commits developed nations to at least double their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation to developing countries from 2019 levels (US$80billion) by 2025.

“Africa needs a coordinated and collaborative approach to ensure that developed nations honour their financial commitments and that climate funding reaches vulnerable societies,” Simalabwi says, “specifically addressing water security, which binds so much of collective social, economic, and ecological objectives.”

Looming crisis

The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) says that global water resource management is “fragmented and inadequate” and highlights the need for urgent action to improve cooperative water management, embrace integrated water and climate policies and scale up investment.

WMO Secretary-General Professor Petteri Taalas said: “Lack of water continues to be a major cause of concern for many nations, especially in Africa. More than two billion people live in water-stressed countries and suffer lack of access to safe drinking water and sanitation.”

According to the WMO report, The State of Climate Services 2021: Water, water-related hazards have increased in frequency over the past 20 years. Since 2000, flood-related disasters have risen by 134% compared with the two previous decades. The number and duration of droughts also increased by 29% over this same period. Most drought-related deaths occurred in Africa, indicating a need for stronger end-to-end warning systems for drought in that region.

“We need to wake up to the looming water crisis,” Taalas said.

South African update

Despite improvements in reservoir levels across South Africa, the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) has reminded South Africans that it is still a water scarce country and encourages the public to continue using water wisely, sparingly, and in a more conservative manner.

Reservoir levels across had experienced “minor improvement” by 27 January 2022, compared with the same period in the previous week and year respectively. Figures released by DWS attributed the marginal rise to torrential rainfall in most parts of the country towards the end of January.

By 27 January, the overall storage capacity of the country’s water levels sat at 95.2%, a minimal increase from the week before at 94.9% but a greater improvement on last year’s 77.3%. In particular the Mohale Dam in Lesotho continues to remain in a strong position at 68.3% – in comparison with 27.4% last year. Also in Lesotho, the Katse Dam was at 99.6%. During the same period last year it stood at 55.8%.

Katse Dam in Lesotho. (Credit: Amada44/Wikimedia Commons)

In the City of Cape Town, stabilising dam levels and steady water use rates were partly attributed to fewer visitors over the holiday period, due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In response to suggestions that water supply constraints could be eased further, a spokesperson from the Department of Water and Sanitation noted that Cape Town dams were only able to maintain such levels due to good rainfall in recent years. It was stressed that it can never be communicated enough that South Africa is water-scarce country.

In 2018 the region experienced severe drought when far-reaching water restrictions were imposed and the city narrowly avoided “Day Zero” when its water supplies would have run dry.

Averting dam collapse

The near collapse of an earthfill dam in the South African Limpopo province has highlighted the requirement for private dam owners to comply with dam safety regulations which enforce that safety inspections are carried out at least every five years.

Safety concerns about the dam, which is owned by the provincial Department of Agriculture, was heightened when it was spilling at full capacity. Engineers employed under the Dam Safety unit of DWS managed to lower the dam level by breaking a part of the wall to avert overtopping.

The near collapse follows two directives issued recently by DWS to the provincial Department of Agriculture to propel them to comply with, and conduct dam safety inspections which should be carried out by an approved professional person.

The Department of Water and Sanitation said it “was faced with this situation due to non-compliance”. As such, it worked closely with the provincial disaster management centre and the provincial government to prevent dam collapse which could have been “catastrophic”.

Change the narrative

During a visit to South Africa’s North West Province, Minister of the Department of Water and Sanitation Senzo Mchunu, urged for a change in the narrative on water service delivery in the region. During February 2022 he met with the Premier of the North West Province, Bushy Maape, and other water and sanitation stakeholders to discuss water challenges in the province and finding solutions to addressing them.

Minister Mchunu emphasised that “water knows no boundaries” and that “local, provincial and the national government must work hand in glove in supplying water to all communities”. He said that on many occasions, municipalities complain about ageing infrastructure which is mainly caused by lack of capacity or lack of funding.

All 25 dams in the province, Mchunu said, must encompass full management plans regarding infrastructure management, environment and leisure, business and tourism activities. He referred to this as an opportunity to generate revenue. However, he added that it remains “a worrying factor that some dam levels are still below average”..

“What we need to work towards is to ensure that there is delivery of water to each household. This will lead to what we envisage: a change of the narrative around water and sanitation, that we are a government that does not care. We have to demonstrate the seriousness with which we take our work by ensuring that we deliver on the mandate that has been given to us as a sector”, Mchunu said.

Decarbonising Ghana

A recent webinar has presented the latest FutureDAMS research on hydropower dams and ways to decarbonise Ghana’s energy system consistent with Paris climate objectives.

As Kuriakose et all explained, in 2019, biomass and petroleum each provided 38% of Ghana’s energy, natural gas 18% and hydropower 6%. The researchers used three future energy scenarios to examine the role of the country’s dams in delivering on its Nationally Determined Contributions as part of climate mitigation and Paris commitments.

Akosombo hydroelectric power station on the Volta River in Ghana. (Credit: Allison Stillwell at English Wikipedia)

Key conclusions from the research were that when considering emissions from reservoirs “Ghana’s planned dams will have a carbon intensity that, during the first decade of operation, exceeds that of coal power stations”.

Furthermore, the full deployment of Ghana’s proposed dams will consume a third of the country’s Paris-compliant carbon budget yet contribute to under 10% of the future electricity demand.

The research concludes that: “Considering Ghana’s current unconditional NDCs are not sufficient to deliver the Paris temperature objectives, energy efficiency and diversifying supply (from wind to floating solar panels on existing reservoirs) offers a lower cost and lower emissions energy future for Ghana than constructing more dams.”