Irish company OceanEnergy has already tested its oscillating water column generators at significant scale in Hawaii, and it's just signed on to a four-year project to test, validate and commercialize its biggest unit yet off Orkney, in Scotland. The OE35, billed as the world's largest capacity floating wave energy device, is certainly an imposing thing to look at. While no dimensions have yet been drawn up for the machine to be built for Scotland as yet, the machine the company built for testing at a US Navy test site in Hawaii measures 125 x 59 ft (38.1 x 18 m), with a draft of 31 ft (9.4 m) and a total weight of 826 tons.

In testing, it ran at a capacity of 500 kW, but the device was, and is, capable of 1.25 MW. Building these things requires shipyard-level facilities – in the Hawaii machine's case, those of Oregon company Vigor. After construction there, the machine was towed to its test site for commissioning.

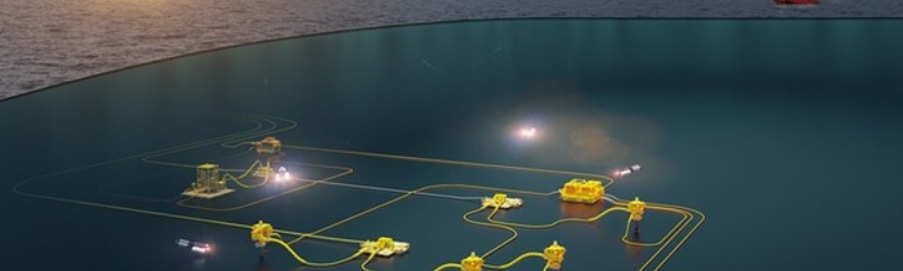

It works on a relatively simple principle. Moored to the ocean floor, the OE35 sits in the sea as waves lap in and out of three large airtight chambers. As the water level in these chambers rises, air is pushed out the top. As it falls, air is sucked back in.

OceanEnergy makes use of a piece of Northern Irish technology to harvest energy from this bidirectional air pressure: the Wells turbine, invented in Belfast in the late 70s. These use a series of symmetrically-designed fan blades, designed to convert air pressure coming through in either direction into the same direction of rotation. Thus, the turbine turns continuously in one direction as the air pumps in and out of the wave chambers, rather than requiring the turbine to keep switching directions every time the air flow reverses.

This is in contrast with Wave Swell Energy's (WSE's) blowhole generator, which works on similar principles, but only harvests energy from air on the in-stroke, allowing the out-stroke air to push out through a valve. Wells turbines are less efficient than unidirectional turbines, and independent analysis appears to suggest WSE's approach of using a single, relatively cheap unidirectional turbine is likely to lead to some of the world's cheapest renewable energy, so perhaps there's something to it. But it's hard to imagine the Wells turbine being so inefficient that it can't harvest more energy from wind in two directions than WSE's device can in one.

A small-scale "OE Buoy" was tested more than a decade agoOceanEnergy

That little mystery aside, OceanEnergy has signed onto a collaboration with 14 partners across industry and academia in the UK, Ireland, France, Germany and Spain to test the OE35 at scale. Co-funded by the EU Horizon Europe Programme and Innovate UK, the €19.6-million (US$19.3-million) WEDUSEA project will proceed in three phases over four years.

First, the team will design and build an OE35 rig tailored to the conditions at the European Marine Energy Test Site in Orkney, Scotland. Then, it'll install and test the machine over two years. The third phase will disseminate the results and focus on commercializing the technology at scale. OceanEnergy has future plans for an OE50 machine capable of 2.5 MW.

“The innovative actions taken in this programme aim to improve the efficiency, reliability, scalability and sustainability of wave energy technology, and reduce the Levelised Cost of Electricity of the technology by over 30%," said Myles Heward, Project Manager at the European Marine Energy Centre. "This will help to de-risk investments in wave energy.”

Rémi Gruet, CEO of the trade association Ocean Energy Europe, adds: “Wave energy is at full-scale stage now and projects like WEDUSEA are paving the way for pilot farms and sector-wide industrialization. As an EU-UK collaboration project, it will demonstrate the potential for wave energy to make a significant contribution to the EU Green Deal target. Wave energy will help smooth production peaks or dips from variable wind and ensure European energy independence.”