Distrust of nuclear power remains strong after Fukushima disaster

Last week, Japan unveiled its basic policy for pursuing a carbon-neutral society. In it, Tokyo overcame its hesitancy toward rebuilding nuclear power plants or extending the life of existing facilities and pledged to do just that.

The shift in energy policy is drastic.

Since the Fukushima nuclear disaster of 2011, Japan has avoided all talk of constructing new nuclear plants or expanding existing ones. The government should be commended for squarely facing reality and taking the first step toward building new facilities.

But the process seems rushed. The government needs to carefully explain the reasons for its change to the public and win a broad nod of approval in moving forward with the policy.

Energy issues and climate change are matters of urgent importance. The war in Ukraine has torn up supply chains, bringing about higher energy prices and a shortage of goods. Meanwhile, global warming continues apace as the world clings to fossil fuels for energy. It is no coincidence that the world is increasingly seeing abnormal weather, such as extreme heat and torrential rain. The international community needs to simultaneously address the energy crisis and climate change.

For the many energy-poor nations in Asia, this in part means maximizing the use of renewable energy, such as solar and wind power. It makes sense to tap all energy sources, including nuclear power, which emits virtually no carbon dioxide.

But the challenges are many.

Any new nuclear plants that are built would run until the end of this century. Japan's new basic policy also notes that nuclear power will be "continuously used in the future." In other words, the government's policy shift impacts the lives of not only this generation but their children and their children's children.

For such an important issue, there has been curiously little national debate. After first being floated in a meeting of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry in September, the outline of the policy was set following just a few rounds of discussion. Meetings were broadcast on the internet, but most people likely had no idea that such a debate was even happening.

Building and maintaining a nuclear plant requires billions of dollars. An accident would incur huge costs for compensating victims. The elephant in the room is the need to find a final disposal site for spent nuclear fuel -- a toxic issue that has not been resolved. Japan's reprocessing plants for spent nuclear fuel, meanwhile, are not ready for operation.

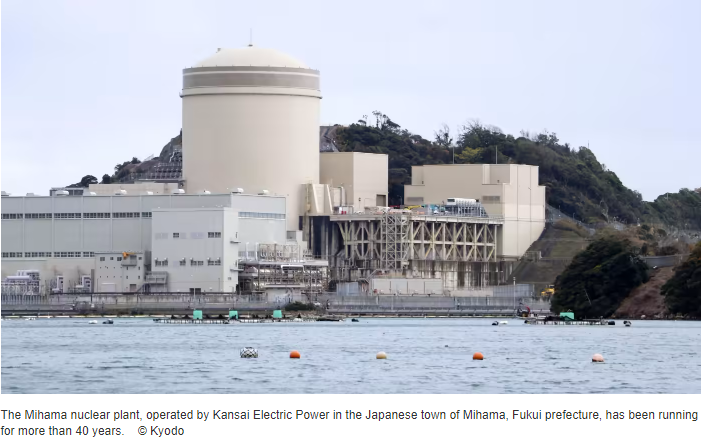

The new basic policy also allows for extending the life span of nuclear plants beyond the current limit of 60 years. Using existing facilities is a reasonable option if safety can be assured.

The Fukushima disaster created widespread anxiety about nuclear plants and strong distrust toward utility companies in Japan. The government should spare no effort in winning the consent of the public and getting this right. Tokyo says it will gather public opinion on the basic policy, but that is not enough.

One suggestion would be to immediately hold town hall-style meetings with the people on the safe and effective use of nuclear power. These meetings should involve the participation of the central government, municipal governments, utility companies, nuclear plant contractors and regulators, and they should be held across the country on an ongoing basis.

How safe are next-generation nuclear reactors? What kind of evacuation plans are needed? Only through a frank exchange of views can trust be built.