The EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme is a vital part of the region’s decarbonisation plans. Simon Göss at carboneer digs into the new rules coming in for the existing EU ETS, and the implementation of the new carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM). Right now, the existing EU ETS covers around 40% of the EU’s emissions (energy sector, industrial installations and aviation). Its scope is being extended to include maritime transport. On top of that, the overall ambition of EU ETS emission reductions until 2030 compared to 2005 is increased to 62%. Fundamental change is also coming to the industrial sector, in particular the phase-out of free allocations of EUAs. CBAM will cover the most emission-intensive sectors: iron and steel, cement, fertilisers, aluminium, electricity. Other products will be introduced in the next decade, with indirect emissions under consideration too. From October 2023 importers in the sectors covered by CBAM must be ready for their monitoring, reporting and verification obligations, ready for the pricing mechanism launch in 2026. In a follow-up article later this month, Göss will explain the next major change: the introduction of a new EU ETS for emissions from buildings and road transport.

Much of the climate ambition of the EU hinges on the bloc’s emission trading system (EU ETS). During December 2022, the Council and the European Parliament reached important agreements on the “Fit for 55” proposals. Specifically, new rules for the existing EU ETS, the implementation of a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) and the introduction of a new EU ETS for emissions from buildings and road transport are in sight. With these revisions implemented the EU would edge closer to its 2030 climate targets, but question marks remain. In this article we unpack some of the most relevant points on changes and updates to the EU ETS I and CBAM.

EU ETS I: new inclusion, rebasing and strong annual cap reduction

Currently, the existing EU ETS covers roughly 40% of the EU’s emissions. They stem from the energy sector, industrial installations and aviation. Maritime transport will be the newcomer and large vessels of 5,000 gross tonnage and above must gradually surrender emission allowances (EUA) for an increasing share of their emissions: 40% in 2024, 70% in 2025 and 100% in 2026. The inclusion of smaller vessels and non-CO2-emissions such as methane and N2O will likely start from 2026 onwards.

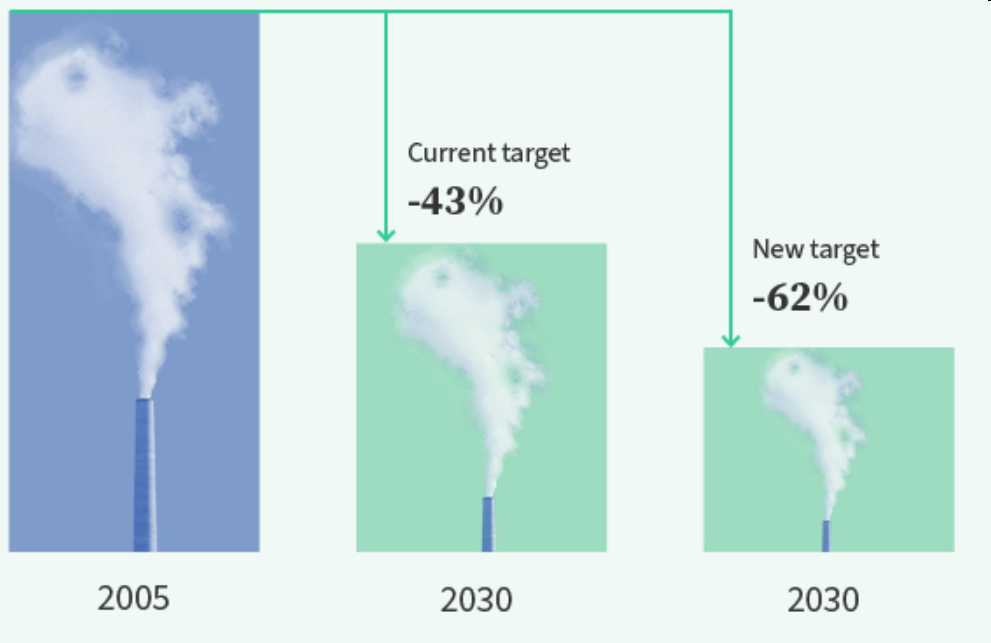

Next to this new inclusion, the overall ambition of emission reductions until 2030 compared to 2005 under the EU ETS increased to 62% (Figure 1). The agreement reached on 18th of December 2022 would thus lead to about 23 million tons less CO2-emissions compared to the EU Commission’s proposal from 2021 and is much more aggressive than the minus 43% that has been the previous reduction target. While the target is politically ambitious, it still falls short of the necessary reductions in the EU to limit global warming to 1.5°C even without taking into account fair share considerations.

To achieve this stronger reduction of 62%, the legislators agreed on a rebasing of emissions: 90 million EUA are taken out of the market in 2024 with another 27 million EUA following in 2026. In addition, the entire emission cap will be reduced by 4.3% annually from 2024 to 2027. From 2028 onwards this linear reduction factor (LRF) will rise to 4.4%. As expected, the market stability reserve (MSR) will continue to take out 24% of surplus EUAs.

Figure 1: Emission reductions targets under the EU ETS I / SOURCE: European Union

All these reductions will lead to significantly tighter supply of EUAs, drive prices and incentivise more decarbonisation especially in industrial sectors. This brings us to the changes for the industrial sector.

Fundamental change for the industrial sector

Most of the industrial sectors under the EU ETS are currently still eligible for free allocation of EUAs. Based on benchmarks on efficient and thus less emission-intensive production, different industrial facilities will still receive free allowances. However, the benchmark system will be overhauled in 2026: the basis for the free allocations will not be a production process, but the product. This facilitates a better comparison between industries.

In addition, industrial companies must have energy audits in place and implement related decarbonisation measures. Otherwise, the free allocation volumes of a facility will be reduced by 20%. Similarly, industrial facilities that are among the worst 20% in terms of carbon-intensity in one sector have to design and implement decarbonisation plans, otherwise their free allocations will be cut by 20%.

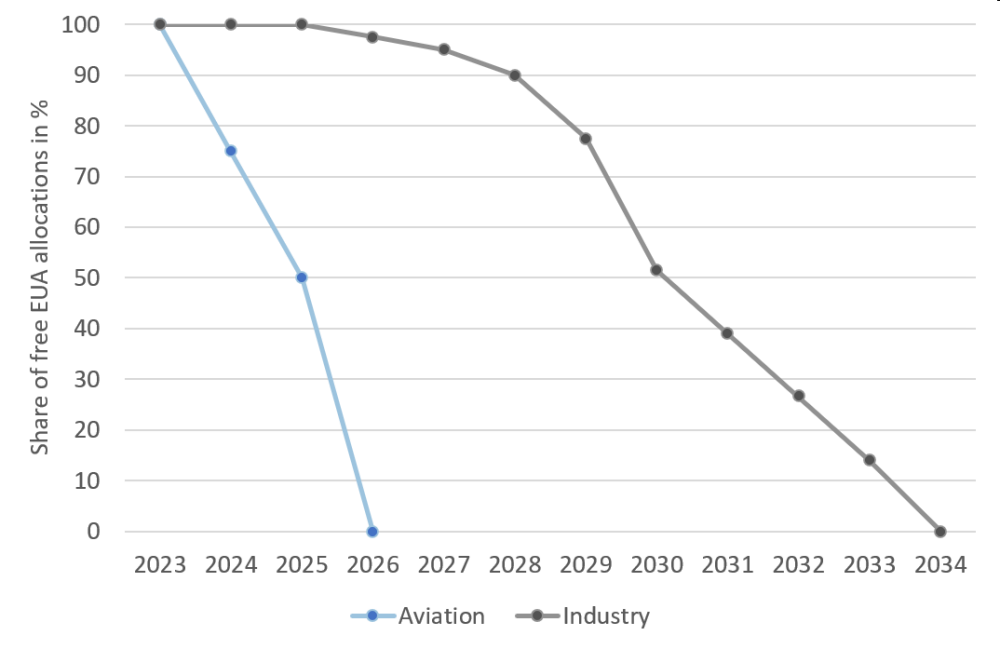

However, the biggest change will be the phase-out of free allocations for industrial players as such. From 2026 onwards, the number of free allowances handed over to industries will be reduced gradually until 2034 when industries have to procure all of their needed allowances through the auctioning mechanism or on the market. Free allocation will be consigned to history.

As becomes clear from Figure 2 below, the phase-out of free allocation for industry starts relatively slowly compared to the phase-out for aviation and picks up speed from the end of the decade. This approach postpones the kicking in of necessary price signals for industrial polluters while allowing the EU industry to prepare and decarbonise in earnest during the next five years.

Figure 2: Share of free EUA allocations over time in aviation and industry / SOURCE: carboneer

The EU Commission expects that about 75 million more EUAs will be auctioned due to the phase-out of free allocations to industry, increasing the auction income. Half of that income should go into the EU Innovation Fund that supports these very industries with the implementation of decarbonisation projects. The other half will be available for the EU member states to support their exporting industries. Which leads us to the next large update as phasing out free allocations is tightly coupled with the introduction of the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

CBAM: pricing imported emissions

At the same time and rate as European industries will not receive free allocations of EUA anymore, importers of certain goods into the EU will have to pay for the emissions of their products. This carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) should on the one hand create a level-playing field between EU and non-EU industries for products in the EU (both paying a similar carbon price) and increase climate ambition in non-EU states (climate instruments and carbon pricing abroad can reduce necessary payments for importers).

Initially, CBAM will cover the most emission-intensive sectors: iron and steel, cement, fertilisers, aluminium, electricity. The new agreements from 13th of December 2022, however, also feature hydrogen, certain precursors and other downstream products such as screws and bolts as imports under CBAM. In addition, the EU Commission will assess the inclusion of other products that might be at risk of carbon leakages such as organic chemicals and polymers into CBAM from 2030 onwards. Indirect emissions at the production facility might also have to be part of the emissions to be reported and consequently paid for by importing companies.

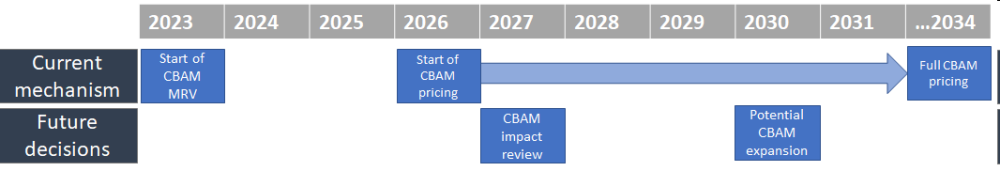

From October 2023 importers in the covered sectors must be ready for their monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) obligations, which start 3 years ahead of the pricing mechanism. Figure 3 depicts the timeline of the CBAM implementation.

Figure 3: CBAM implementation timeline / SOURCE: carboneer

Two main contentious issues remain for CBAM:

How will reporting and verification methods and schemes really look like and work for imported goods?

How to compensate or support companies that produce in the EU and must purchase EUAs but export to non-EU countries where no or less ambitious carbon pricing rules exist?