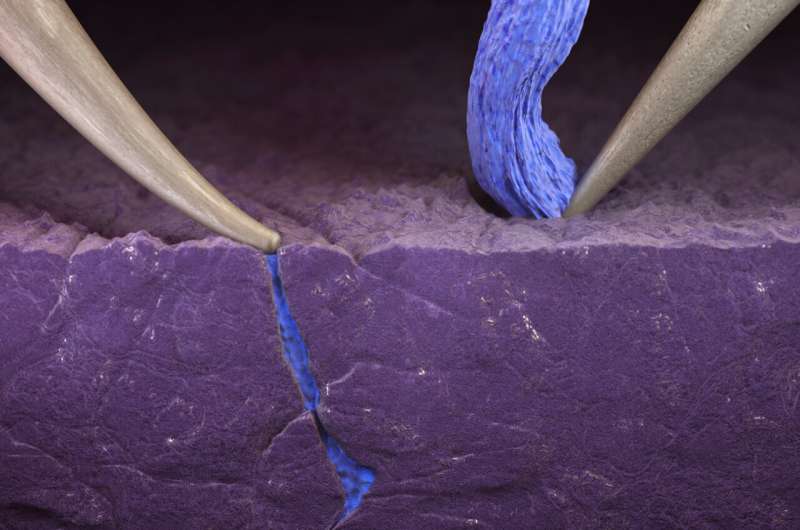

This artist’s rendition shows one probe bending from applied pressure, causing a fracture in the solid electrolyte, which is filling with lithium. On the right, the probe is not pressing against the electrolyte and the lithium plates on the ceramic surface, as desired. Credit: Cube3D

New lithium metal batteries with solid electrolytes are lightweight, inflammable, pack a lot of energy, and can be recharged very quickly, but they have been slow to develop due to mysterious short circuiting and failure. Now, researchers at Stanford University and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory say they have solved the mystery.

It comes down to stress—mechanical stress to be more precise—especially during potent recharging.

"Just modest indentation, bending or twisting of the batteries can cause nanoscopic fissures in the materials to open and lithium to intrude into the solid electrolyte causing it to short circuit," explained senior author William Chueh, an associate professor of materials science and engineering in the School of Engineering, and of energy sciences and engineering in the new Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

"Even dust or other impurities introduced in manufacturing can generate enough stress to cause failure," said Chueh, who directed the research with Wendy Gu, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering.

The problem of failing solid electrolytes is not new and many have studied the phenomenon. Theories abound as to what exactly is the cause. Some say the unintended flow of electrons is to blame, while others point to chemistry. Yet others theorize different forces are at play.

In a study published Jan. 30 in the journal Nature Energy, co-lead authors Geoff McConohy, Xin Xu, and Teng Cui explain in rigorous, statistically significant experiments how nanoscale defects and mechanical stress cause solid electrolytes to fail. Scientists around the world trying to develop new, solid electrolyte rechargeable batteries can design around the problem or even turn the discovery to their advantage, as much of this Stanford team is now researching. Energy-dense, fast-charging, non-flammable lithium metal batteries that last a long time could overcome the main barriers to the widespread use of electric vehicles, among numerous other benefits.

A scanning electron microscopy video that shows lithium plating as it takes place on a solid electrolyte. Credit: Xin Xu, Geoff McConohy and Wenfang Shi

Statistical significance

Many of today's leading solid electrolytes are ceramic. They enable fast transport of lithium ions and physically separate the two electrodes that store energy. Most importantly, they are fireproof. But, like ceramics in our homes, they can develop tiny cracks on their surface.

The researchers demonstrated through more than 60 experiments that ceramics are often imbued with nanoscopic cracks, dents, and fissures, many less than 20 nanometers wide. (A sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers thick.) During fast charging, Chueh and team say, these inherent fractures open, allowing lithium to intrude.

In each experiment, the researchers applied an electrical probe to a solid electrolyte, creating a miniature battery, and used an electron microscope to observe fast charging in real time. Subsequently, they used an ion beam as a scalpel to understand why the lithium collects on the surface of the ceramic in some locations, as desired, while in other spots it begins to burrow, deeper and deeper, until the lithium bridges across the solid electrolyte, creating a short circuit.

The difference is pressure. When the electrical probe merely touches the surface of the electrolyte, lithium gathers beautifully atop the electrolyte even when the battery is charged in less than one minute. However, when the probe presses into the ceramic electrolyte, mimicking the mechanical stresses of indentation, bending, and twisting, it is more probable that the battery short circuits.

Theory into practice

A real-world solid-state battery is made of layers upon layers of cathode-electrolyte-anode sheets stacked one atop another. The electrolyte's role is to physically separate the cathode from the anode, yet allow lithium ions to travel freely between the two. If cathode and anode touch or are connected electrically in any way, as by a tunnel of metallic lithium, a short circuit occurs.

As Chueh and team show, even a subtle bend, slight twist, or speck of dust caught between the electrolyte and the lithium anode will cause imperceptible crevices.

"Given the opportunity to burrow into the electrolyte, the lithium will eventually snake its way through, connecting the cathode and anode," said McConohy, who completed his doctorate last year working in Chueh's lab and now works in industry. "When that happens, the battery fails."

The new understanding was demonstrated repeatedly, the researchers said. They recorded video of the process using scanning electron microscopes—the very same microscopes that were unable to see the nascent fissures in the pure untested electrolyte.

It's a little like the way a pothole appears in otherwise perfect pavement, Xu explained. Through rain and snow, car tires pound water into the tiny, pre-existing imperfections in the pavement producing ever-widening cracks that grow over time.

"Lithium is actually a soft material, but, like the water in the pothole analogy, all it takes is pressure to widen the gap and cause a failure," said Xu, a postdoctoral scholar in Chueh's lab.

With their new understanding in hand, Chueh's team is looking at ways to use these very same mechanical forces intentionally to toughen the material during manufacturing, much like a blacksmith anneals a blade during production. They are also looking at ways to coat the electrolyte surface to prevent cracks or repair them if they emerge.

"These improvements all start with a single question: Why?," said Cui, a postdoctoral scholar in Gu's lab. "We are engineers. The most important thing we can do is to find out why something is happening. Once we know that, we can improve things."