The blended fuel, called hythane, could also be a major step forward in the transition to clean energy, says Amit Kumar, who advised the provincial government in developing its Hydrogen Roadmap.

"You can transport it in current pipelines, you can use it in your appliances and you can use it for heating purposes with current equipment," says Kumar, NSERC/Alberta Innovates/Cenovus Associate Industrial Research Chair in Energy and Environmental Systems Engineering.

"You don't need to make any modifications," he adds, provided the amount of hydrogen in the blended fuel doesn't exceed between 15 and 20% by volume.

Kumar's own research involves modeling various energy pathways—using a combination of renewable and non-renewable energy—to reduce overall carbon emissions in a cost-effective way over the next few decades.

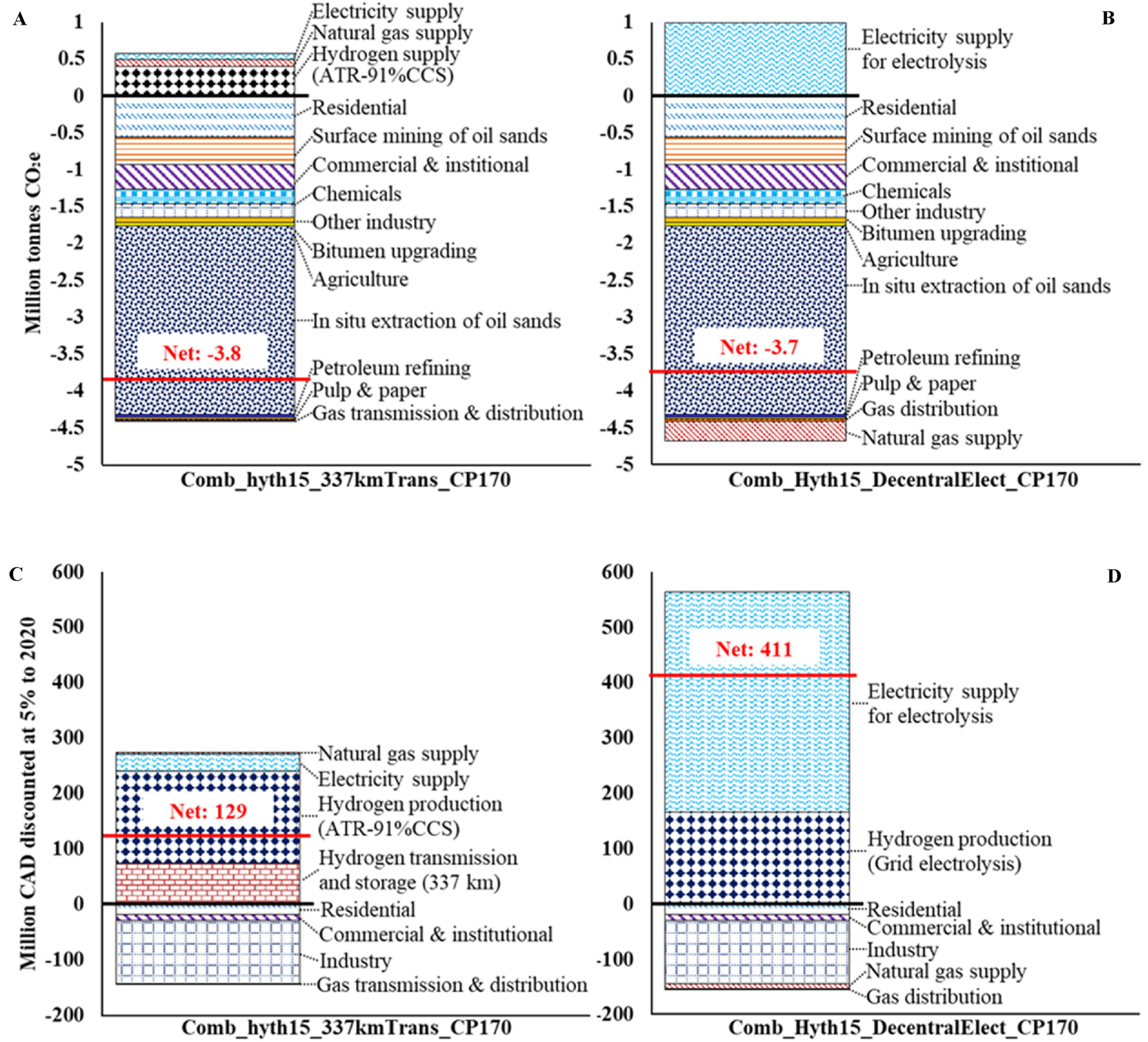

In his latest study, published in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Kumar and a team led by engineering Ph.D. student Matthew Davis evaluated 576 long-term scenarios across global jurisdictions between 2026 and 2050, varying according to hydrogen blending intensity, carbon policy and hydrogen infrastructure development.

Because of its low cost, Kumar and his team found that introducing hythane into natural gas networks offers a "near-term opportunity for capacity building, technology learning and building confidence in the consumer.

"Economies will benefit from the infrastructure scale-up through job creation, attracting investment and technology exports," he says.

One of the cleanest sources of energy, hydrogen produces only water when it is burned or used in a fuel cell.

Producing what's called "gray hydrogen" does release greenhouse gas by converting natural gas to carbon dioxide and hydrogen. But combining that process with carbon capture and storage—another area in which Alberta is a global leader—produces cleaner "blue hydrogen."

Capturing at least 42% of the carbon emissions will produce an overall "well-to-combustion" reduction across the chain. The more carbon emissions are reduced, the cheaper the fuel becomes due to savings in the carbon tax, he adds, especially when carbon prices are more than $300 per ton.

"We produce a large amount of hydrogen in Alberta, but most of it is used in the industrial sector in bitumen upgrading and fertilizer production," Kumar notes.

"If we convert our infrastructure to produce blue hydrogen—and that means adding carbon capture and storage—to all of these production facilities, that's a big win for us."

The Alberta Carbon Trunk Line is now using only one to two million tons of its 14.5-million-ton capacity, so there is "a huge capacity to transport more," says Kumar.

The challenge ahead is to progress to "green hydrogen" using wind, solar and biomass energy. But the costs of hydrogen from these sources are high compared with blue hydrogen.

Beyond Alberta, there is an enormous opportunity to export hydrogen along with our expertise in production and carbon capture, says Kumar, especially to fast-developing countries in the Asia-Pacific.

But for now, using a blend of hydrogen and natural gas is low-hanging fruit in the pursuit of a clean energy economy.

"You don't need a major investment," he says. "You can use the existing infrastructure and slowly replace it to take on a higher percentage of hydrogen. It gives you time in a slow transition."

Alberta's Hydrogen Roadmap, a key part of the province's economic recovery plan, identifies key markets such as residential and commercial heating, transportation, power generation and storage and chemical processing. In addition to clean fuel, hydrogen is also used to produce fertilizer, ammonia and other chemicals.

Blending hydrogen with natural gas is one of the recommendations included in the roadmap, says Kumar, which the government is now considering.