The United Kingdom’s nuclear renaissance

The United Kingdom’s nuclear industry is expanding, with the U.K. government committed to supporting the build of more civil nuclear power plants (deployments up to 24 GW by 2050)1 while also undertaking large-scale decommissioning work in parallel.2 The defense sector is experiencing growth with the decommissioning, operation, and new build of submarines, plus managing the U.K.’s deterrent.3 Although the civil and defense programs are separate, they draw on the same group of skills and people.The United Kingdom’s nuclear renaissance

The United Kingdom’s nuclear industry is expanding, with the U.K. government committed to supporting the build of more civil nuclear power plants (deployments up to 24 GW by 2050)1 while also undertaking large-scale decommissioning work in parallel.2 The defense sector is experiencing growth with the decommissioning, operation, and new build of submarines, plus managing the U.K.’s deterrent.3 Although the civil and defense programs are separate, they draw on the same group of skills and people.

The growth in skills demand

With this sector growth, there is an increasing demand for both “skills for nuclear” and “nuclear skills.”4 The “skills for nuclear” cover more general roles such as construction workers, project and program managers, and civil and electrical engineers. These roles are typically combined with short nuclear familiarization training to understand the importance the nuclear industry places on safety and security.

On the other hand, the “nuclear skills” are industry specific and cover roles such as safety case, health physics, and nuclear science (e.g., decontamination, reactor physics, and materials characterization). The experience required for these roles must be gained in a nuclear setting, whereas “skills for nuclear” can be developed across the broader economy. For example, a nuclear project manager and a nonnuclear project manager will undergo just as much training to be competent in their roles. The nonnuclear project manager has the opportunity to do this across a wider range of sectors; therefore, the retention of individuals becomes important to ensure that the nuclear industry can achieve what it needs to do.

Handling alpha material, compared to other nuclear material, requires a different skill set. With gamma emitters radiation exposure is the main hazard, whereas contamination is the main hazard with alpha. Because alpha materials require careful handling and containment, as well as some degree of shielding from gamma decay products, the skills and knowledge needed are unlike those required in other parts of the nuclear sector.

In the U.K. industry, as part of our approach to meet regulatory requirements and ensure we have the correct people and skills to undertake a task, we have the concept of SQEP (suitably qualified and experienced person), meaning that an individual must be both suitability qualified (with the correct qualifications, be those occupation qualification or formal education, and fit to carry out the work) as well as an experienced person (with the correct training and demonstrable experience to undertake a task safely and securely).

From a current resourcing perspective, there is a finite number of people working in the U.K. nuclear industry. In order for organizations to use this resource pool effectively, it is important to manage the growth in demand across the industry to ensure that the U.K. as a whole can achieve what it sets out to do.

Future challenges arise when the resource pool gets smaller and different organizations across the industry will be using the same skills at the same time. This means the U.K. must develop a strong future pipeline of workers on which to draw. The development of people within the industry is vital to ensure that peaks in demand can be managed in a sustainable way and that the nuclear jobs market continues to thrive. The management of the nuclear skills pipeline in an effective and sustainable way is key. By doing this, the nuclear industry can deliver what they need to in the future without the detriment to other sectors of the U.K. industry or individual organizations. This is a collective challenge that the nuclear industry must manage together in order to realize the ambition of new build, achieve decommissioning progress, and honor the ongoing commitment to the deterrent.

Reports by the U.K. government4 and the Nuclear Skills Strategy Group5, 6 have predicted a national peak demand estimated at between 98,000 and 105,500 full-time equivalents in the next 10 years for the entire civil and defense nuclear workforce. These are large numbers for the U.K., especially when considered against a national picture of new civil and defense programs.3 This places greater importance on the correct workforce planning to ensure the right skills are available at the right time, in the right place for individual organizations involved and also the country as a whole.

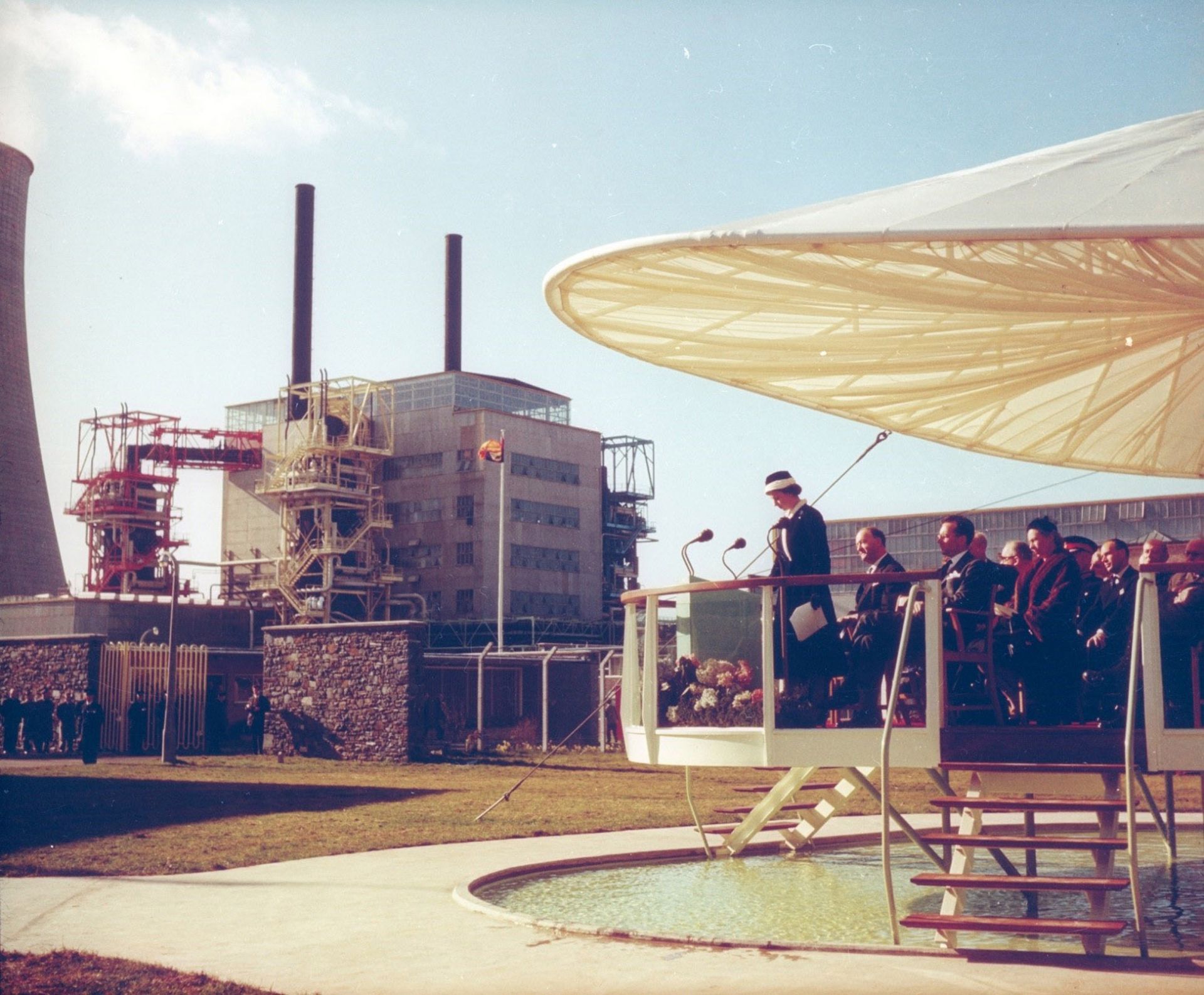

Fig. 1. Queen Elizabeth II opening Calder Hall, the world’s first commercial nuclear reactor, in 1956. (Photo: Sellafield)

Sellafield’s nuclear heritage: A case study

The Sellafield site in the northwest of England has had a long history with nuclear on both civil and defense sides, in particular, managing nuclear material safely and securely.

Following the signing of the McMahon Act in 1946, the U.S. Congress prevented America from sharing atomic secrets with other countries. This led the U.K. to create its own atomic program, with developments at the Sellafield site beginning in 1947 to produce plutonium to address defense objectives.

A few years later, Queen Elizabeth II opened the world’s first commercial nuclear power station at Calder Hall in 1956 (Fig. 1). Calder Hall was dual purpose: the reactors were generating electricity while also producing plutonium for the U.K. defense program.

Sellafield has played an important role in spent fuel management by reprocessing fuel at the Magnox Reprocessing Plant and the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant. Due to the nature of reprocessing contracts, the site has generated an international reach with customers from across the globe.

With both reprocessing operations and Calder Hall, Sellafield separated a significant inventory of plutonium from these activities. Initially the concept was near-term storage and deployment of a major fast neutron breeder reactor program; however, development of this approach was abandoned in the late 1970s. Therefore, the site requires careful management to ensure safe and secure storage of this inventory while also decommissioning legacy facilities.

Sellafield has been home to world-leading research and development activities for most of its existence. Today, the National Nuclear Laboratory has its Central Laboratory on the site, where a wide range of nuclear research, including on alpha materials, is undertaken.

More recently, the U.K.’s reprocessing program has ended. The Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant ceased reprocessing in 2018 when its commercial contracts had been fulfilled. Magnox Reprocessing Plant completed reprocessing in July 2022.2 Operating since 1964, the facility safely reprocessed nearly 55,000 metric tons of fuel. This is approximately half of the total volume of fuel ever processed anywhere in the world. The new operational focus is to ensure that there are sufficient skills and operational life left to carry out post-operational clean out ahead of the decommissioning required over the coming decades.

Required skills at the Sellafield site

Nuclear research, decommissioning, and related waste management are significant challenges to all involved.2 At Sellafield (Fig. 2), this covers not only decommissioning nuclear reactors but also complex challenges with both alpha- and beta/gamma-contaminated legacy nuclear facilities associated with many aspects of the fuel cycle. Sellafield employs 11,000 people directly, with even more people in the supply chain being supported by this work,7 so the skills needed are varied.

Compared with operations where work is well defined through plant flowsheets, operating procedures, and consistent site infrastructure, successful decommissioning requires a different set of skills. Innovative yet safe and effective approaches are essential for success. Decommissioning involves one-of-a-kind tasks, and in the case of complex facilities this can mean projects can take several years to complete due to their unique aspects. Whether that is knowing how to change a leaded glove in a 40°C working environment under time constraints due to dose uptake or planning to retrieve from a spent fuel storage pond for the first time in 60 years, each activity requires a specific set of skills to complete the task as safely as possible.

Sellafield has been operating for over 70 years and has a 100-plus-year mission ahead to fully decommission the site.7 This involves building new storage facilities to help manage our inventory of spent fuel and special nuclear materials. We need to continue to grow the skills to deliver our mission. Whether that is through using Spot the robotic dog (Fig. 3) or developing our project management profession,8 we have been developing ways to reduce the hazard to humans while also decommissioning the site in a safer, sooner, and more cost-effective way. This is to make sure we are creating a clean and safe environment for future generations.

Constantly evolving skills needs

The skills needed for Sellafield to undertake its mission are constantly evolving as we seek to decommission the site. For example, projects specific to decommissioning alpha facilities require careful planning, with special consideration given to the waste generated from these activities. In just one project, professionals including project managers, waste strategy experts, operators, safety case specialists, and business managers all could be involved.

Workforce planning is a challenge when decommissioning at the Sellafield site, as the activities are often one of a kind, so there is limited comparable information available. This places greater importance on two things: effective workforce planning across the life cycle of facilities (right skills, right people, right time, right place) and access to the best talent pipeline, enabled through training programs and training facilities. This allows us to have effective knowledge transfer and information management.

By doing these two things, the U.K. industry should be able to respond to changes in workforce demand and have a more sustainable approach to skills planning. Good workforce planning means taking a proactive approach so we can understand the future demand, thereby maintaining and developing skills and capability for critical future programs, which underpins the building of new training facilities and creating knowledge transfer programs.

At Sellafield, skill changes often occur in conjunction with decommissioning technology advancements, for example, using remotely operated vehicles in ponds or unmanned aerial vehicles to conduct civil inspections of buildings on the site. Other skill changes occur faster, for example, the use of IT systems to communicate across multiple locations driven by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Initiatives such as “no hands in some glove boxes” look at ways of using remote technologies for operations and maintenance activities presently undertaken within glove boxes. With other approaches, we are looking to decommission items within glove boxes and the glove box itself. For example, to help better manage the waste from alpha-related decommissioning, a robotic arm has been developed with a laser-cutting module to reduce the size of items to save space for final disposal. Although we try to make the use of robotics in these environments business as usual, for now we recognize that humans will still be needed for certain decommissioning activities. The skills we need for operating this equipment will develop over time, and the industry needs to be able to flex to address this demand.

The need for sustainable alpha skills

With the increase in demand across the entire sector, there will also be growth in specific areas, such as the skills required to manage alpha materials. Handling alpha material, compared to other nuclear material, requires a different skill set. With gamma emitters radiation exposure is the main hazard, whereas contamination is the main hazard with alpha. Because alpha materials require careful handling and containment, as well as some degree of shielding from gamma decay products, the skills and knowledge needed are unlike those required in other parts of the nuclear sector. It is predicted that the U.K. will need to fill more than 2,800 alpha roles within the next 10 years,9 with demand far outstripping the number of people currently in this niche area of the industry. This is expected to be a challenge due to a range of factors:

The U.K., along with companies that operate with special nuclear materials, has developed a national program to develop a response to this challenge: The UK Alpha Resilience and Capability (ARC) Programme. This means that operating companies across civil and defense sectors are working together to understand how to use a finite pool of resources in the best way possible, as well as grow the resource pool in a sustainable way.

Fig. 2. Aerial view of Sellafield in 2021. The site is 2 square miles. (Photo: Sellafield)

Fig. 3. Spot the robotic dog collecting information by laser scanning and gamma radiation imaging. (Photo: Sellafield)

The UK ARC Programme

The UK ARC Programme is a proactive, long-term collaboration between the U.K. government, nuclear industry, and the wider nuclear sector. It seeks to identify targeted projects and investments in specialist skills, expertise, and facilities to sustain and enhance the U.K.’s world-leading alpha capabilities.

The program is made up of nine partner organizations from industry, civil nuclear regulator, and governmental bodies (Nuclear Decommissioning Authority; Sellafield Ltd.; Dounreay Site Restoration Ltd.; Atomic Weapons Establishment; National Nuclear Laboratory; Nuclear Skills Strategy Group; Office for Nuclear Regulation; Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy; and Ministry of Defence’s Defence Nuclear Organisation).

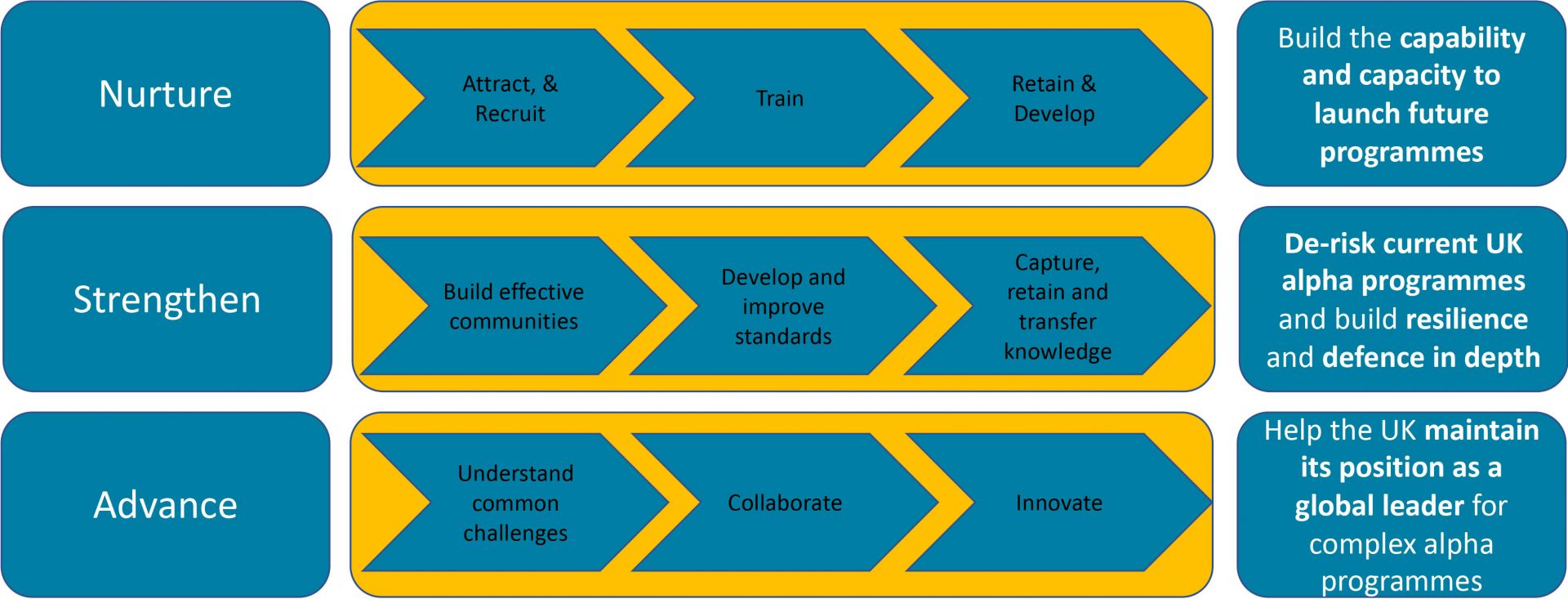

It identifies the gaps, synergies, and opportunities across the partner organizations, building a collaborative environment where the organizations can work together to solve common challenges (see Fig. 4). A video, “An introduction to the UK ARC Programme,” has been made to explain the program in a bit more detail (youtube.com/watch?v=X0vHqCTLQqM).

Fig. 4. The UK ARC Programme themes and structure. (Credit: Sellafield)

Impact on the U.K. nuclear industry and alpha operations

So far, the ARC Programme has identified common challenges within our alpha programs, such as engineering and design challenges, the transfer of knowledge, and the development of alpha skills. We have looked at the training partner organizations deliver to the U.K.’s alpha operators.

The ARC Programme has identified that there are limited training facilities for alpha skills development. The training, where provided, has a heavy reliance on learning on the job, which means that becoming an SQEP has taken an extended amount of time and increased levels of supervision. A small number of experts have been relied on to provide and deliver the training. Each individual organization has been following its own training specification with no coordination or adoption of national standards.

To address this, the ARC Programme has undertaken three steps to support the attraction, recruitment, and training of the U.K.’s alpha operators:

ARC has built an inactive Glove Box Training Facility located near the Sellafield site, which replicates on-plant conditions (Fig. 5). This allows a safe environment for all operators to develop and improve their skills. A state-of-the-art facility means that training can be delivered in a more engaging way, which reduces the time to train alpha operators. The partners can now train other areas of the program. This helps increase knowledge sharing across the partner organizations and the wider U.K. nuclear industry.

ARC has created an enhanced training program that ensures operators are more “plant ready” for beginning work in an active environment. Although on-plant training cannot be completely eliminated, the training facility has reduced the amount required.

ARC has developed a first-of-a-kind National Glove Box User Standard that facilitates worker mobility. It was developed in collaboration with the National College for Nuclear and provides a recognized national standard and qualification for the U.K.’s alpha operators. This gives further confidence and assurance to employers and employees, knowing that their training is valid across all ARC partner organizations. It provides a platform for the implementation of future changes to working practices as training needs develop and change over time. It also allows the sharing of knowledge and best practices across the sector. Given the potential shared challenges that both the U.K. and U.S. face in this area, this also offers an opportunity for future collaboration on this topic.

The Glove Box Training Facility will become a hub for the U.K.’s alpha training and will provide support to ARC partners, academia, the supply chain, and international partners. As part of creating an enhanced training program for alpha operations, the ARC Programme has undertaken a systemic approach to training; a blended approach of instruction, discussion, and practical activities to cover the knowledge, skill, and behavior requirements was then developed. A refresher program has also been developed to ensure experienced operators are working to the same standard.

Fig. 5. A worker undergoing training at the U.K.’s dedicated Glove Box Training Facility at Sellafield. (Photo: Sellafield)

Looking to the future for the ARC Programme

Across the industry, we have learned a lot working with special nuclear materials, and we still have more to learn. We appreciate that the skills we need to manage alpha materials will evolve over time across civil and defense sectors and we need to be aware of how these changes affect the industry.

We are not going to solve the alpha skills challenge overnight, but we can take important steps to help understand how demand will change in the future to create a sustainable workforce. By working together to solve common challenges, we can have a proactive approach to workforce planning, develop a strong talent pipeline, and create training facilities to grow and maintain our skills. This means we can create a sustainable alpha workforce that will have the necessary skills across the U.K.’s civil and defense nuclear sectors. Additionally, by reaching out to U.K. and international partners, we can ensure we are sharing best practices across the world.

Concluding remarks

With the U.K. nuclear industry expanding through new civil and defense programs, our nuclear industry is facing unprecedented demand. Due to the range of skills required and the long timescales to which the industry works, there is significant challenge in workforce planning over this period. Accurate forecasting of workforce supply and demand is pivotal for the U.K. industry.

The ARC Programme has brought together the U.K. civil and defense nuclear industry to help tackle common issues together. Part of this work is developing national standards, as this offers an opportunity to create a mobile and agile workforce of the future. The portability of skills in the nuclear industry is vital to success, especially to make supply meet the demand of people and create a sustainable workforce plan. The ARC Programme is continuing to work with its partner organizations to implement interventions effectively, ensuring program objectives and benefits are realized and sustained for the long term.

Henry Hickling has a chemistry background and currently works in the external affairs department at Sellafield Ltd. on projects such as the Alpha Resilience and Capability (ARC) Programme to help develop skills resilience across the U.K. nuclear industry.