This is according to Solutions for Our Climate (SFOC), a Seoul-based non-profit organisation focused on climate action and energy transition, which performed a study into the country’s offshore wind permitting system.

Namely, offshore wind developers in South Korea are required to consult 29 pieces of law across 10 different ministries, a process that can take more than ten years, according to government estimates.

SFOC says that the 98-per-cent group that is yet to come near a final decision is “stuck in bureaucratic nightmare” due to this slow and unclear permitting procedure.

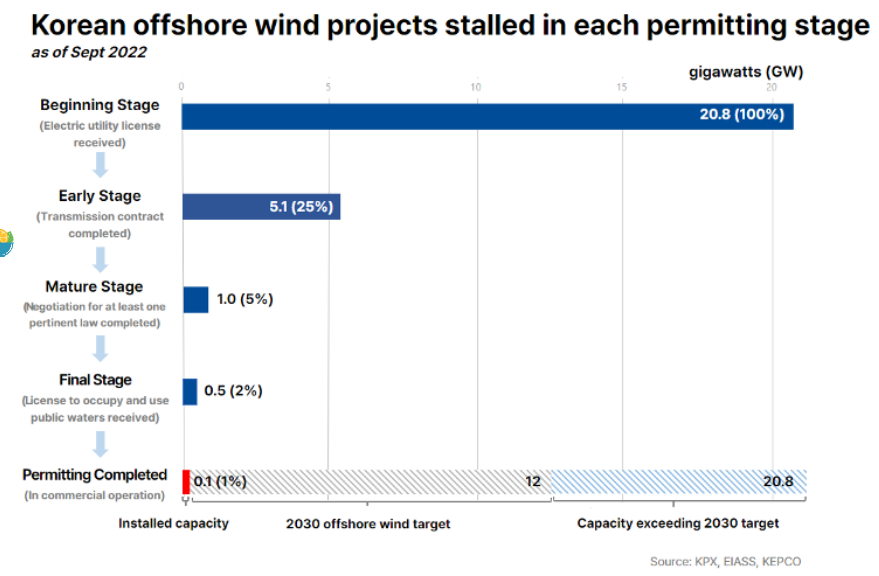

As of 2022 September, 70 offshore wind projects received electric business licenses (EBLs), which is the initial stage of permitting. However, only four offshore wind farms (making up for 2 per cent of the total number) saw the process completed so far. And, out of these four, only two are operational, SFOC pointed out.

With two projects in commercial operation making up for less than 1 per cent of South Korea’s 2030 target of 12 GW, the government must streamline permitting to meet its targets for the end of this decade, the non-profit says.

Lack of clarity and a streamlined approach in permitting is not only burdensome for offshore wind developers, but also poses a major obstacle to accelerating offshore wind energy growth in the country, according to SFOC.

“What South Korea lacks are not technical capabilities or interest from developers. Rather, it is the absence of a clear permitting procedure”, said Eunbyeol Jo, head of the renewable permitting team at Solutions for Our Climate. “We need political will and leadership from the government to unlock our country’s tremendous potential for wind energy”.

SFOC highlighted efforts in Europe that are being made to speed up the consenting processes both on an EU level and within national policy reforms taking place in some of the Member States. Here, the non-profit pointed to the EU’s measures under the REPowerEU strategy that are being taken to shave time off of permitting for wind and solar projects, with an aim to bring it down from five to under two years.

Denmark has also adopted a policy which centralises the licensing procedure to a single public agency, which consults and coordinates with relevant stakeholders, SFOC said.

“Having a dedicated public agency that studies and identifies appropriate offshore wind zones can significantly boost efficiency and speed up renewable growth”, Eunbyeol Jo said.

SFOC also reminded that a bill which would centralise maritime zoning and permitting was already introduced in the Korean National Assembly back in 2021. However, the proposed bill has remained on hold in subcommittee review for the past two years, according to the non-profit.

The organisation further added that the new permitting legislation in Europe would shift the burden of proof for environmental protection from developers to public agencies.

“It is the responsibility of the government, not of developers with vested interests, to designate offshore wind zones by properly assessing environmental, economic, and social impacts. This can also help the developer focus on project development rather than jumping through administrative hurdles”, Eunbyeol Jo said.