The shift is partly a response to “range anxiety”—the fear of being stranded because EV batteries don’t have enough power to get to the next charging station—an idea so familiar in discussions of electric vehicles that it was spoofed in a Ram Super Bowl ad last month.

But this concern is unwarranted for a large share of EV customers, according to research from the University of Delaware, published Feb. 21 in the journal Energies.

Willett Kempton, a University of Delaware professor, and his team looked at driving data for 333 gasoline vehicles over one year in the Atlanta area, and then created a model to see the extent to which various EV options would have been able to meet the needs of those drivers.

They found that 37.9 percent of the drivers would have been able make all of their trips for the year using a small EV like a Nissan Leaf as their primary vehicle and charging at locations like home, work or wherever the vehicle was parked and charging was available. The hypothetical vehicle had a 40 kilowatt-hour battery and range of 143 miles.

To put this a different way, more than a third of drivers were able to meet 100 percent of their needs with an EV with a relatively small battery, and didn’t need to make any additional trips for the sole purpose of charging.

Keep in mind, drivers that can’t meet their needs in this scenario aren’t stranded indefinitely by the side of the road. They just need to find charging options outside of their typical routines, which usually means stopping at fast-charging stations on longer trips.

I asked Kempton what he sees as the main takeaways from this research. One of them, he said, is that small batteries can meet the needs of a large share of drivers.

“Smaller batteries have all kinds of advantages,” he said, among them cost and weight, not to mention smaller carbon footprints because they require less electricity and fewer metals like lithium. And Kempton added another benefit—“you’re reducing pedestrian injuries”—because the cars weigh much less than models with large batteries, which diminishes the severity of collisions with people and other vehicles.

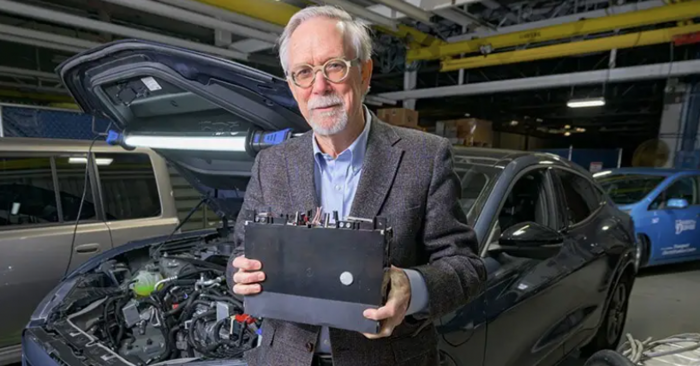

University of Delaware’s Willett Kempton holds an electric vehicle battery module in his research lab at UD’s Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus. Credit: University of Delaware/ Evan Krape

An example of the price gap: The 2023 Leaf has a projected range of 143 miles for the entry-level model and a base price of $28,040; and the 2023 Ford Mustang Mach-E has a projected range of 224 miles for the entry-level model and a base price of $45,995. Prices do not take into account tax credits.

About the only time that the longer range is essential is for cross-country trips, when a vehicle with a larger battery is going to need fewer stops. But cross-country driving trips are rare for most drivers.

“It’s cheaper to rent a car for two days (per year) than to spend 10 grand on a much bigger battery,” Kempton said.

The co-authors, who also included researchers from the Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia and Georgia Tech, looked at scenarios involving EVs with various sizes of batteries and charging systems. They found that longer-range vehicles would rarely, and, for some drivers, never, need to use the upper reaches of their range.

The paper helps to confirm some things we knew or at least strongly suspected. Much like drivers don’t need gigantic pickup trucks to get groceries, drivers don’t need 300 miles of range when the large majority of their trips are 20 miles or less. (Cars and light trucks in the United States get used for one hour per day and travel 35 miles, based on averages compiled by the Federal Highway Administration.)

I reached out to Stephanie Searle of the International Council on Clean Transportation, a global leader in EV research, to get her impressions on the paper.

She said the study’s analysis is simple but effective, and makes some important points.

“A lot of the news lately has been around EV range getting longer and longer, but the fact is, if a lower-range car will do, it’s going to be better for the customer’s wallet and for the environment,” she said in an email. “Lower range means smaller batteries, and that reduces the upstream environmental impact from mining and battery production. Smaller batteries also means more efficient EVs that cause lower (greenhouse gas) emissions from electricity production.”

The paper’s driving data comes from a trove of information gathered from 269 households in the Atlanta area starting in 2004. Drivers agreed to have GPS devices in all of the vehicles in their households. The results were terabytes of information that have since been used by several transportation researchers.

He said the findings show the potential demand for low-cost EVs with small batteries, a part of the market that has few options in the United States.

“This kind of data allows (automakers) to say, “OK, there’s actually a market segment here,’” he said.