The alliance of small island developing states (Aosis) wanted new guidelines on carbon credits to recommend that a mandatory 5% levy on carbon credit revenues. The money would go to the Adaptation Fund to finance projects like seawalls to protect against rising sea levels.

This idea was supported by the expert panel of the Integrity Council on the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM), the organisation drawing up the guidelines for the industry.

But, with sellers like the NGO Conservation International and buyers like the Spanish bank BBVA opposed, the ICVCM’s board decided to make the 5% levy optional.

Adao Soares Barbosa, a climate negotiator for the south-east Asian island nation of Timor-Leste, told Climate Home that “mandatory measures would be good”, because if it is optional then “it might not be fulfilled”.

But both he and Guinea’s climate negotiator Alpha Kaloga said they were pleased that a 5% levy was there, even if it is optional. “I believe that this principle will become the rule in the near future,” said Kaloga.

In 2022, the UN estimated that funds for climate change adaptation in developing countries were five to ten times lower than needed. By 2030, the finance needed for adaptation would reach between $160 and $340 billion.

But in 2020, rich countries provided just $29 billion and only aim to provide $40 billion by 2025.

At the last UN climate negotiations in Egypt, countries agreed to “urgently and significantly” scale up finance from developed countries for adaptation measures in developing nations.

Experts overruled

Pedro Martins Barata leads the Environmental Defence Fund’s work on carbon credits and co-chairs the ICVCM’s expert panel. He said most of the panel had supported making it mandatory but the board decided not to heed their advice.

“It was a political decision by the board”, said another expert panel member Lambert Schneider from the Institute for Applied Ecology. Barata said not all of the board’s members supported their decision.

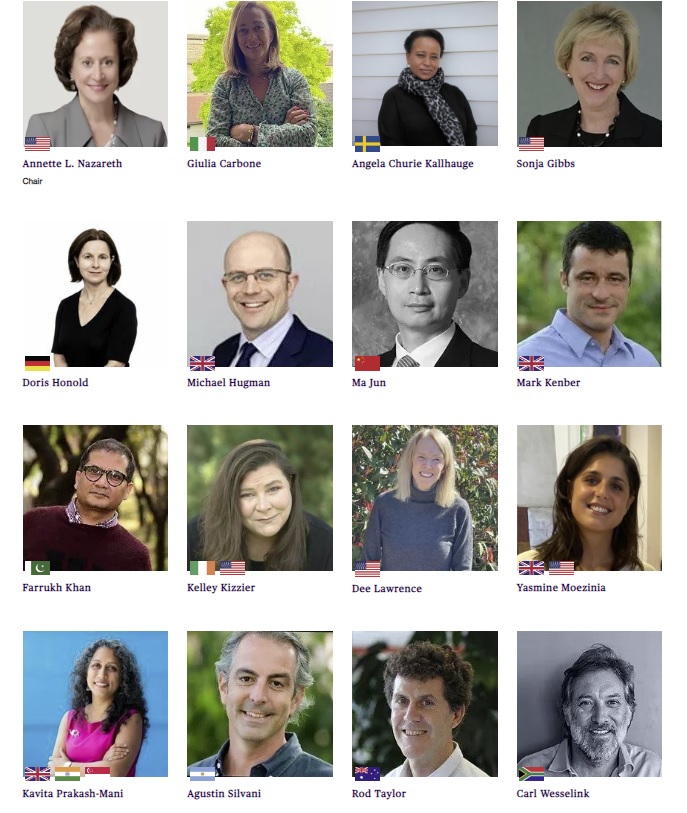

The governing board of the ICVCM

Barata said that, although the funds raised would be limited, a mandatory levy would be important symbolically. He added it would also help carbon markets become popular in communities like Pacific islands or the world’s poorest countries, where emissions are low that there aren’t going to be many carbon-cutting credit projects.

The counter-argument, he said, is that a mandatory levy adds extra costs to carbon offsets and will therefore mean less carbon-cutting projects and more emissions.

Among those making this argument in the consultation over the new guidelines was the American non-profit Conservation International, whose board includes celebrities like actor Harrison Ford and business figures like Walmart’s Rob Walton.

An unnamed employee of Conservation International argued that a levy would be an “undue additional financial burden”.

‘Reverse carbon tax’

Emergent, an intermediary that develops forest carbon credit projects, said that a levy would “constitute a reverse carbon tax on jurisdictions/projects in those developing countries that the fund is meant to benefit”.

An anonymous staff member of the Spanish bank BBVA argued that, because carbon credit projects are usually based in developing countries and bought in developed ones, they are “already an inherent funding mechanism from developed economies to developing countries”.

Carbon Market Watch’s Gilles Dufrasne, a member of the expert panel, told Climate Home he disagreed. “Adaptation finance is not just development finance,” he said, “it’s money needed to adapt to the catastrophic impacts of climate change.

“Claiming that this supports the host country is a bit like saying you’re supporting farmers when you buy food. Sure, that’s true in a way, but that’s not really why you’re buying the food,” he added. “It’s quite disingenuous to try to pass this off as an act of kindness towards the seller.”

The ICVCM will continue consultations on whether to make a 5% levy mandatory in its next set of guidelines, scheduled to launch in 2025. ” It’s a gap that will have to be plugged in future updates,” said Dufrasne.

The funds generated by a levy are likely to be small in comparison to developing countries’ needs.

A spokesperson for the Adaptation Fund told Climate Home they have a pipeline of projects not yet funded approaching $0.4bn. They said they “will wholehearteldy welcome the 5% share of proceeds when they become available” as they largely rely now on voluntary donations from governments and companies.

Predicting how much a share of proceeds could raise is difficult. But, with the voluntary carbon market at its current size, it is likely to be significantly less than $0.1 billion.

“Its money, its not nothing but its not going to be by itself changing the needle in terms of the needs to address adaptation” said Barata.