An electric car charges at a mall parking lot on June 27, 2022 in Corte Madera, California. Credit: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

An electric car charges at a mall parking lot on June 27, 2022 in Corte Madera, California. Credit: Justin Sullivan/Getty ImagesThat would be the equivalent of dialing down the entire U.S. economy to zero CO2 emissions for two years.

But to fulfill the promise of the strongest-ever pollution standards proposed for cars and trucks, the Biden administration is relying on both automakers and consumers to embrace the electric vehicle revolution.

Within a decade, two-thirds of passenger cars, half of freight delivery vehicles and a quarter of heavy trucks purchased would be electric under the plan. In 2022, EVs accounted for just 7 percent of vehicle sales.

Administration officials believe that the goal is reachable thanks in part due to historic multi-billion dollar investments that both the federal government and the auto industry are making in the wake of the clean energy spending bills by Congress, including last year’s Inflation Reduction Act.

“This is a moment of transformation,” said White House Climate Advisor Ali Zaidi in a briefing with reporters. “It’s a moment of transformation that accrues to the benefit of our kids, who rely on us to make decisions so that they can breathe cleaner air. It benefits our energy security because…we will be less reliant on imports from foreign countries. And it’s a huge boon to investing in America.”

But the oil industry may well challenge the effort, backed by fossil-fuel reliant states that have led past lawsuits against climate regulations. “This deeply flawed proposal is a major step toward a ban on the vehicles Americans rely on,” said Mike Sommers, president and CEO of the American Petroleum Institute. “As proposed, this rule will hurt consumers with higher costs and greater reliance on unstable foreign supply chains.”

Driving Down Oil Demand

As U.S. electricity has become cleaner because of the shift away from coal and to cheaper natural gas and renewable energy, transportation has overtaken the power sector as the largest source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. And though the Biden administration has taken heat for its slow pace of rolling out regulations to further curb power sector emissions, the new vehicle standards could mean far more in reducing the nation’s greenhouse gas footprint.

The vehicle standards could also minimize or eliminate the eventual impact of recent pro-oil development decisions that Biden has made—like the approval of ConocoPhillips’ massive Willow project in the Arctic or the recent big lease sale in the Gulf of Mexico, with oil the source of nearly all transportation emissions. If U.S. demand for oil collapses, so would the economic viability of high-priced oil projects.

Environmental groups that had blasted the administration’s approval of Willow as a decision that would lock in greenhouse gas emissions for decades praised the approach that the Biden EPA took to spur a move away from gasoline-powered transport.

“The EPA clean air proposals announced today will slash billions of tons of climate pollution, along with health-harming pollution that causes thousands of premature deaths annually,” said Fred Krupp, president of Environmental Defense Fund, in a statement. “EPA has launched us on a critically important journey to a clean transportation future.”

The success of the effort will hinge somewhat on the mix of vehicles that Americans buy in the years ahead, but the EPA concluded that the sizes of passenger vehicles won’t be as big of an issue as it was in the past. Even large SUVs can have zero emissions if they are powered by batteries instead of internal combustion engines, the EPA reasoned.

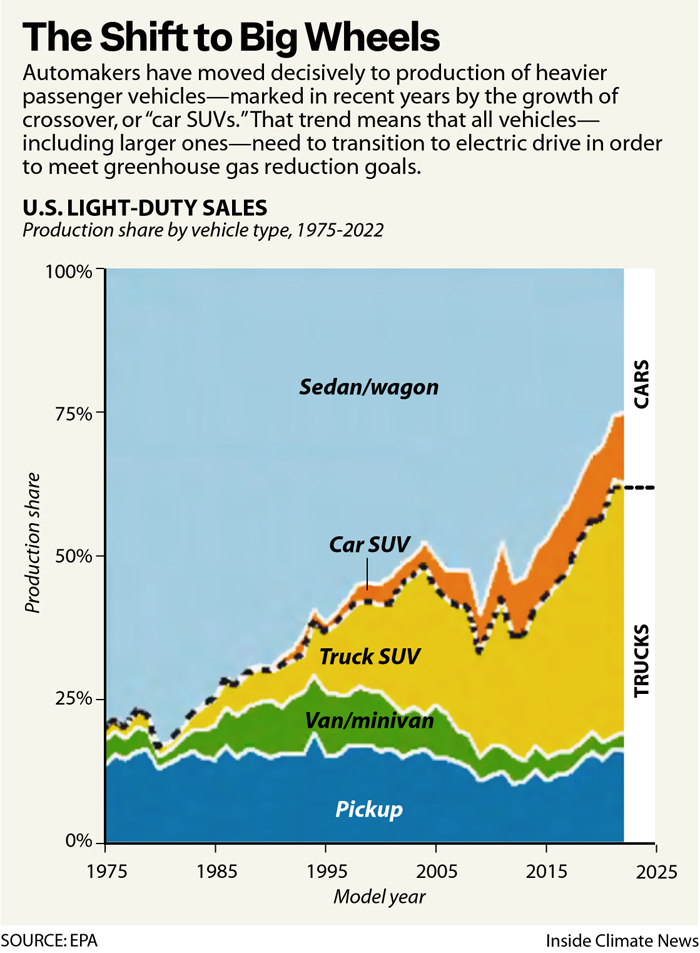

Because of the EPA’s practice of setting different, more lenient standards for light trucks than for smaller passenger vehicles, previous vehicle greenhouse gas regulations did not drive down emissions as quickly as projected.

For example, when President Barack Obama put the first vehicle GHG emissions standards into effect in 2012, 64 percent of new vehicle sales were classified as passenger vehicles, with the remaining 36 percent of sales being light trucks, such as pick-ups. Those shares have completely reversed, with light trucks now accounting for 63 percent of new sales, and passenger vehicles, for 37 percent of sales. Traditional sedans now represent just 26 percent of fleet sales, replaced by taller and heavier vehicles like sport utility vehicles and crossover, or “car SUVs,” with lower fuel economy ratings, more lenient emissions standards and more greenhouse gas emissions per mile driven.

These larger vehicles are far more profitable for automakers than sedans, and the manufacturers say it’s what consumers want. Some environmental advocates have called for EPA to abandon separate standards for cars and SUVs.

“These and other loopholes make Swiss cheese out of a solid regulation and must be rejected,” said Dan Becker, director of the Safe Climate Transport Campaign at the Center for Biological Diversity.

But instead of eliminating the differing standards for cars and SUVs, EPA proposed to phase the difference down over time. It will be easier for manufacturers to meet more stringent standards for larger vehicles as more of them are powered by battery, the agency concluded. Automakers would be required to reduce fleet-wide emissions from cars 52 percent from Model Year 2026 to Model Year 2032, to 73 grams of CO2 per mile.

For light trucks, they would have to achieve a 57 percent reduction, to 89 grams of CO2 per mile. The EPA anticipates that the fleet-wide average reduction would be 56 percent, to 82 grams per mile.