The measure was part of a bill intended to accompany Russia’s ratification of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change in September. Instead, the world’s fourth-largest carbon polluter scrapped the proposal after the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP) warned it would raise costs for companies and delay investment.

“After consultations with the government, it was decided to abandon the specific regulatory requirements,” the press department of the Economy Ministry, which is drafting the bill, said by email. “The government will have the right to decide after Jan. 1, 2024 what measures to introduce if Russia is forecast to miss its emissions targets.”

“AFTER CONSULTATIONS WITH THE GOVERNMENT, IT WAS DECIDED TO ABANDON THE SPECIFIC REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS”

Economy Ministry

Rising global temperatures pose potentially devastating risks for Russia, where thawing of the vast permafrost area covering more than half the country threatens damage to buildings, energy pipelines and other infrastructure. With the Arctic warming twice as fast as the rest of the world, Russian government estimates put economic losses at $2.3 billion a year.

While President Vladimir Putin has questioned whether human activity is solely responsible for climate change, he finally agreed to ratify the Paris accord this year and declared that Russia must do whatever it can to mitigate the effects of global warming. It’s a particular challenge for Russia’s economy, which is heavily dependent on oil and gas production and mining. The permafrost zone contains 15% of Russia’s oil and 80% of its gas operations.

Fining companies

Companies would have been fined for exceeding their emissions targets under the abandoned legislation. The measure wasn’t a requirement of the Paris accord, since Russia has a low goal for greenhouse gas reductions. But advocates argued it would demonstrate the Kremlin’s commitment to confronting climate change, and also bring Russia into line with international practice as part of efforts to shift the economy away from carbon-heavy industries.

The RSPP attacked the draft proposals at a meeting in parliament in March, warning they would lead to increased energy prices and inflation that would “negatively affect the well-being of ordinary people” and force companies to abandon investment plans. An RSPP spokesman didn’t immediately respond to a request to comment.

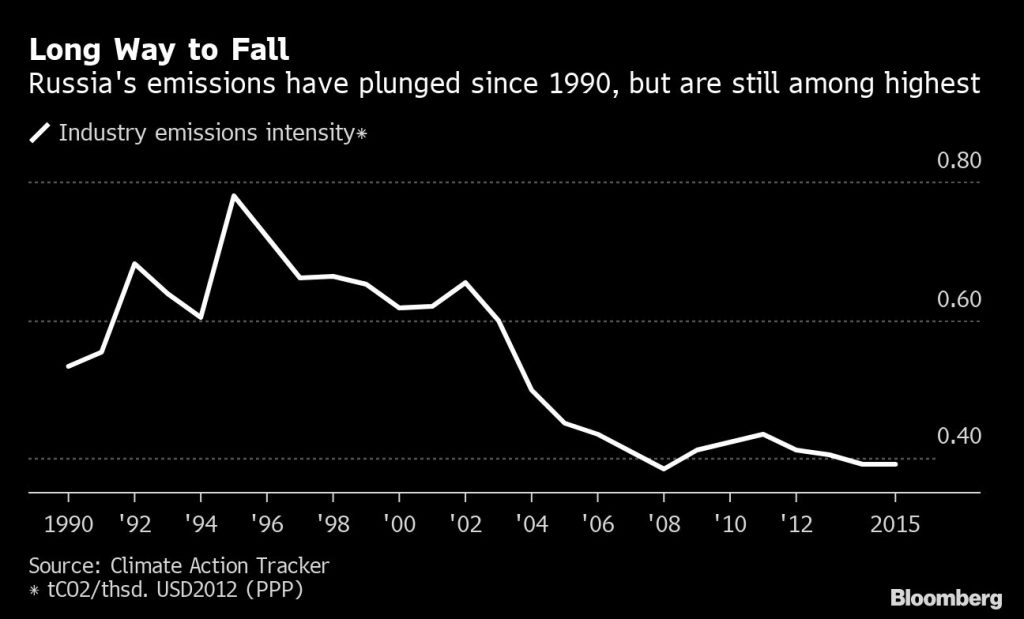

Critics also argued the measure was unnecessary because Russia can increase its emissions over the next decade and still meet its self-imposed target under the Paris accord. That’s because it uses 1990 as the baseline reference year for reducing greenhouse gases, the year before the collapse of the Soviet Union triggered one of the most devastating economic contractions in modern history.

Russia is pledging to limit emissions to 70% to 75% of baseline levels by 2030. It has until the end of 2020 to present its new long-term strategy for reducing carbon emissions, according to Ruslan Edelgeriev, Putin’s senior adviser on climate change.

“Russia is choosing to delay the process of establishing a system for reducing carbon emissions,” said Georgy Safonov, head of the Center for Environmental and Natural Resource Economics at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics. “The 2030 goals have already been met, so there’s a feeling that we don’t need to do anything to cut emissions before then.”

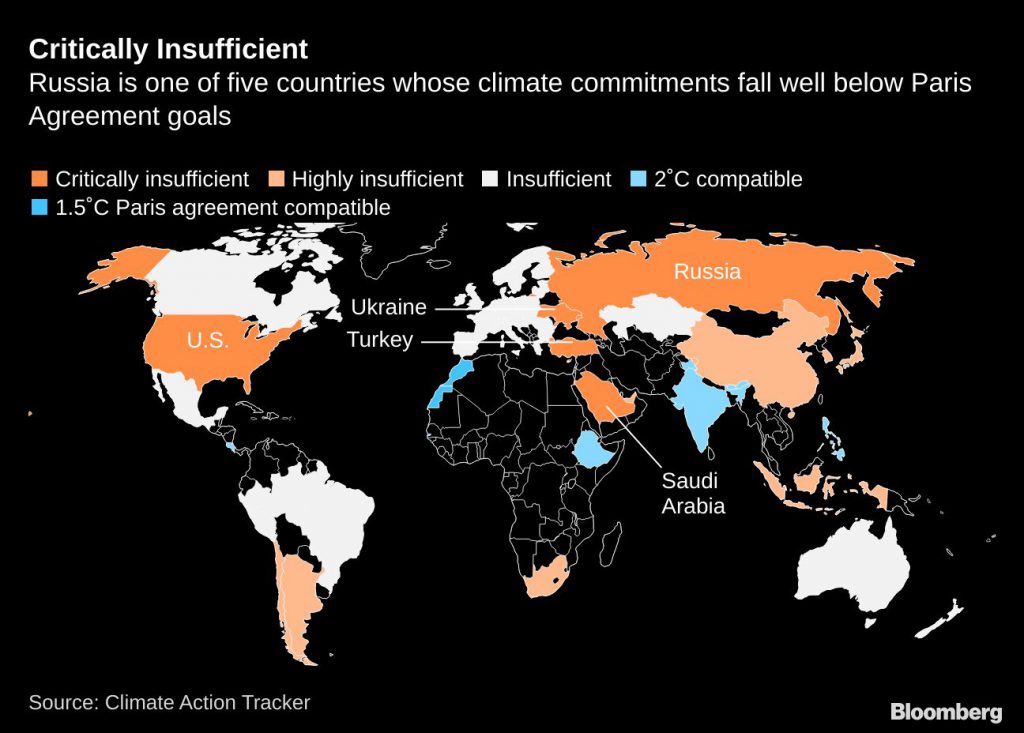

Even so, Russia is rated among the countries whose efforts are “critically insufficient” to help meet the Paris accord’s overall goal of limiting worldwide warming to well below 2 degrees celsius above pre-industrial levels this century, according to the Climate Action Tracker research group. The London-based Carbon Tracker think tank calculates that the world’s major oil and gas companies need to cut combined production by 35% by 2040 to keep emissions within the Paris targets.

Unlike most developed countries, Russia has no state system for monitoring and regulating companies’ greenhouse gas emissions. Some publicly-listed companies in Russia collect data and set targets voluntarily, following pressure from international investors. In many countries, fines and taxes collected from carbon emitters are invested in renewable-energy projects.

Russia also needs to redirect money into the green economy if it wants to stay competitive abroad, according to Mikhail Yulkin, general director for the Center for Environmental Investments, a consultancy based in Arkhangelsk. In particular, a European Commission proposal for a carbon border tax could have a big impact on Russia’s economy, Yulkin said in comments first published in Kommersant newspaper.

“The model on which the Russian economy has survived for the past 20 years is dying,” Yulkin said. “We just need to find a convenient method of transferring funds to sectors that promote the development of low-carbon industries.”