Energy has been central to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In every year since 2013, when the global infrastructure initiative was first announced, to 2022, the energy sector accounted for the majority of investments and construction deals signed.

Until very recently these investments were dominated by fossil fuel projects, triggering concerns that countries signed up to the BRI would replicate China’s emission-intensive development pathway. In doing so, they might become heavily dependent on fossil fuels just as the world wakes up to the urgent need to transition to renewables.

Then, at the UN General Assembly (UNGA) in September 2021, President Xi Jinping announced that China would no longer support the construction of coal-fired power plants abroad. He also stated that the country would “step up” support for “green and low-carbon energy” in fellow developing countries.

Data from the Green Finance and Development Center, at Fudan University in Shanghai, suggests that this may finally be happening. In the first half of this year, investments and contract signings for solar and wind power projects accounted for nearly 42% of Chinese engagement in the overseas energy sector, compared to 26% in the whole of 2022 and 15% in 2021. In terms of value, engagement in solar and wind grew slightly compared to the first half of 2022 off the back of an uptick in construction contracts. Coal projects saw zero investment, while gas and oil projects accounted for around 22% of each.

At the same time, however, overall investment of Chinese companies in the overseas energy sector has declined to its lowest level since the start of the BRI ten years ago. The year 2021 was also the first since 2000 to see no new loans to overseas energy projects from China’s state-run banks.

“Green development” on the BRI was discussed at one of three high level forums taking place during the Third Belt and Road Forum in Beijing on 16 and 17 October. As the BRI enters its second decade, will it be able to fulfil the 2021 promise to “step up” support for green energy in developing countries? What opportunities and obstacles stand in its way?

Cancelled Coal projects

In the years running up to Xi’s UNGA announcement, coal power projects on the Belt and Road became a hotspot for controversy and discontent. Projects such as one at Lamu in Kenya, Hunutlu in Turkey, Celukan Bawang in Indonesia, and Gwadar in Pakistan, to name a few, attracted criticism for their emissions implications, failure to properly consult local communities, and risks to the local environment.

Since 2021, however, many of these projects have been cancelled. Forthcoming analysis by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) indicates that 36 coal power plants, representing nearly 36 gigawatts (GW) of capacity, have been cancelled since September 2021. Some projects have still moved to construction even after Xi’s announcement, particularly “captive” coal power plants designed to serve industrial facilities. CREA argues that a further 19.2 GW worth of coal power that is currently in the pipeline should be cancelled as the projects have still yet to receive permits or finance. The organisation also says that a further 10 plants, for which permitting or financing deals have already been signed but have not yet entered construction, “should be converted to renewables”.

“A project will need to be built to ensure no breach of contract. However, because no physical infrastructure is in place yet, it is still possible for contracts to be renegotiated to renewables,” explains CREA director Nandikesh Sivalingam.

Renewables face challenges

The expansion of wind and solar energy along the Belt and Road may be easier said than done, however. Dr Wei Shen of the Institute of Development Studies at Sussex University, UK, explains that high levels of debt and rising interest rates on loans have increased project risk and affected investor sentiment. Added to this, he argues, Chinese institutions tend to be relatively inflexible and slow to respond to the changing overseas investment environment.

In 2019, people in Nairobi marched to the Kenyan Ministry of Energy and the Chinese embassy to protest a planned coal power plant in Lamu. The BRI project was cancelled in November 2020. / IMAGE: © Paul Basweti / Greenpeace

New partnerships

Specifically, Shen’s research suggests that Chinese energy companies investing overseas can no longer rely on the finance and construction model, underwritten by sovereign guarantees of the host country, that has dominated BRI infrastructure projects until recently. Rather, companies will need to be more creative and flexible in finding financing and working with non-Chinese parties. To date, private companies have proven much more capable of doing this than China’s big state-owned companies. As a result, we see a number of renewable energy infrastructure partnerships involving companies from both China and elsewhere, including Europe and the US, but also emerging markets such as the UAE and Turkey.

For example, a construction contract signed for a 115 megawatt (MW) solar plant in Upington, South Africa, in the run-up to Xi Jinping’s state visit to the country in August, involved a consortium of Chinese state-owned companies, China Energy Engineering Corporation and Gezhouba, South African partners, as well as France’s EDF.

Vested interests in developing countries

The obstacles are not just financial, however. Two recent reports from the Green Finance and Development Center called attention to the “intricate political-economic circumstances and vested interests” of the energy sectors of Pakistan and Vietnam, two of the largest destinations for China’s overseas energy investments over the last decade. The authors note that both local government and state-owned companies in Pakistan have an interest in preserving the coal power and mining industries.

Moreover, despite the declining costs of renewables, these interests are unlikely to shift anytime soon, due to insufficient risk presented to coal investors in Pakistan’s power sector, report co-author Haneea Isaad tells China Dialogue. Similarly, in Vietnam the authors point to the interests of coal power plant operators and coal importers, who have signed long term-contracts on the supply of coal. The authors conclude that the “acceleration of green energy transition is not a one-size-fits all model.”

A different approach to financing

Another way Chinese financiers and companies could help accelerate energy transitions in Belt and Road countries is by aiding the early retirement of coal power plants they have been involved in building over the last decade.

One way to do that is by conditional refinancing of such projects. This involves offering a new loan at a lower interest rate to pay back the original loan, on the condition that the plant be retired earlier than its planned lifespan, which is often 30 to 40 years. Freed-up capital or portions of the low-interest loan could then be invested in renewable projects. Such early retirements could also lower the risk of Chinese-backed plants becoming “stranded assets” as countries move towards lower-emission power generation as part of their climate pledges and energy security goals.

“Chinese sponsors have a large portfolio of plants that can potentially be phased down early,” explains Professor Christoph Nedopil, director of the Griffith Asia Institute and co-author of the Pakistan and Vietnam reports. “Early retirement can be a win-win-win situation: for the Chinese sponsors who are cutting losses of existing plants and improving their returns through combined investments into renewables, for the host country’s economy, and for the environment.”

Another approach particularly relevant to countries with high sovereign debt could be “debt-for-climate” swaps. These could involve payments owed to Chinese policy banks being partially cancelled or renegotiated in return for the early retirement of coal power assets or construction of renewable energy projects. The swap could also be extended to include agreements on Chinese companies’ involvement in new (and more profitable) renewable energy projects, Nedopil explains.

“The financial instruments are aplenty,” says Isaad. “However, this is all very theoretical at this point. To my knowledge, the Chinese have not been brought in on these initiatives yet and without that we cannot progress even an inch.”

Benefitting from China’s solar overcapacity

China is the major supplier to solar projects across the world, accounting for over 80% of solar panel manufacturing worldwide, according to the International Energy Administration (IEA).

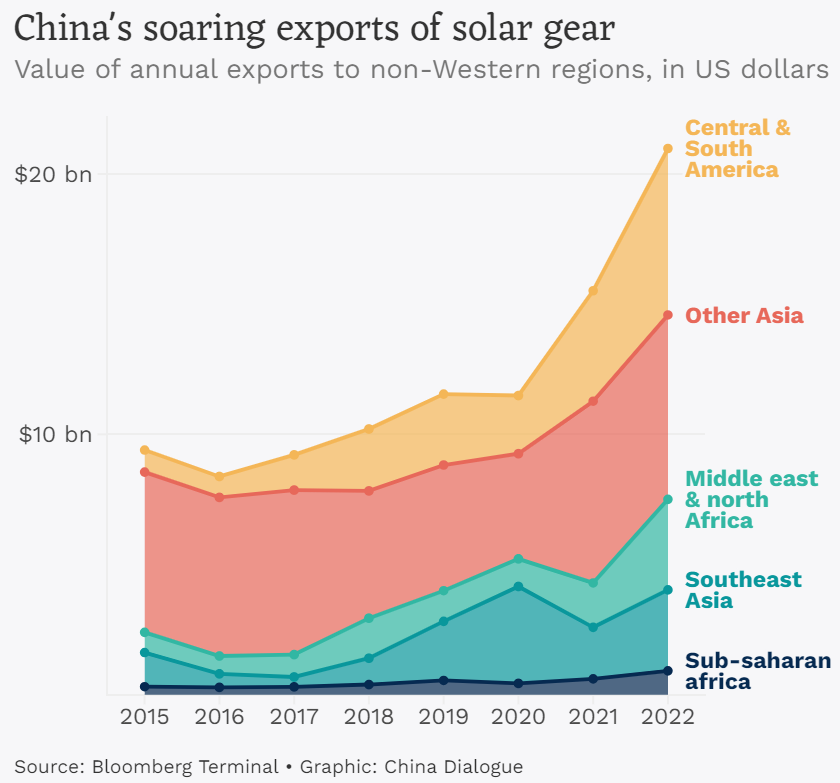

Despite the complexities of transitioning to cleaner energy investments overseas, exports of solar components manufactured in China are soaring. In the first half of 2023, they increased 13% compared to the same period last year, according to Chinese customs’ data, one of very few bright spots amid China’s current economic travails.

While the European market accounted for around half of those exports, data compiled by China Dialogue indicates that Belt and Road geographies are also a part of the picture of this boom in demand for Chinese solar components.

Yunnan Chen from the Overseas Development Institute, a think-tank headquartered in London, notes that the first decade of energy infrastructure investment on the Belt and Road was shaped by the overcapacity and spillovers from China’s domestic economy. So too will the second decade of the BRI feel the influence of that economy, says Chen. As China shifts towards renewables and develops its world-leading solar and battery manufacturing power, Chinese companies will seek out new markets abroad.

China’s involvement in the energy transitions of the Belt and Road is complex and evolving. With an increasingly difficult global economic environment, innovative solutions to make true on Xi’s UNGA promise to “step up” support for green and clean energy overseas will be needed, including new types of financing and international partnerships.

Following the 3rd Belt and Road Forum, policymakers from BRI countries and beyond will be looking to the high-level forum on green development for some hint of new approaches to “greening” the initiative.