(Mike Eliason/Santa Barbara County Fire Department via AP, File)

(Mike Eliason/Santa Barbara County Fire Department via AP, File)

The first category accounts for up to half of all bushfires. Alongside dropped cigarettes, escaped burn-offs and campfires, and sparks from equipment, there are sparks from downed powerlines.

Electricity networks mitigate this risk mainly by making sure the poles and wires are in good condition and by maintaining the vegetation around them.

Some networks also reduce the risk of their lines causing bushfires by ‘de-energising’ or shutting off the power—especially when strong winds are forecast to accompany high bushfire danger.

In Australia, only SA Power Networks currently has the authority to de-energise lines to reduce the risk of bushfires. In April, it cut power to Port Lincoln and surrounding areas as a precaution to reduce the risk of a fire starting when‘the wind was so strong that it was moving… powerlines around quite violently.’

De-energising has consequences. Frozen and chilled food melts and rots. Traffic lights don’t work. Petrol pumps don’t work. Nor do landlines and some mobile phone towers. And people who rely on electrical appliances for their health or security, from air-conditioners to life-support equipment, can be in danger if they don’t have backup power.

So networks try to keep the extent, frequency and duration of de-energisation events to a minimum. SA Power Networks has only used its de-energisation power on 15 occasions since 1985, and then only for a few hours each time.

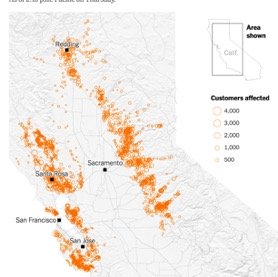

By contrast, in the midst of the terrible wildfires which gripped California in October, the state’s largest utility, Pacific Gas and Electric, declared public safety power shutoff (PSPS) events which cut off the power to up to two million people for up to three days straight.

Area in Northern California de-energised by PG&E on 9 October 2019 (image from NYT)

Area in Northern California de-energised by PG&E on 9 October 2019 (image from NYT)

Not happy. The governor called for customers to be compensated. The regulator opened an investigation and called for corrective action to ensure that no such widespread blackouts happen again.

PG&E was already in trouble, having filed for bankruptcy in response to the financial challenges associated with the catastrophic wildfires that occurred in Northern California in 2017 and 2018.Those fires resulted in a flood of lawsuits and wildfire liabilities the company estimated could cost it up to $30 billion.

Once bitten, it now appears to be overly cautious when faced with the risk of its infrastructure causing more wildfires. In the US, utilities are legally liable for the damage caused by wildfires if their equipment sparks them—but not for the costs to customers of cutting off the power.

No bankruptcies on the horizon here, although in 2014 SP AusNet (now AusNet Services) was forced to pay survivors of Victoria’s 2009 Black Saturday bushfires nearly $500 million. The Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission found that the deadly Kilmore East-Kinglake bushfire was caused by an ageing SP AusNet power line.

There are three other reasons why large-scale de-energisation is unlikely to happen here any time soon.

One, we have very high reliability standards, so most poles and wires are in good condition.

Two, network regulation in Australia does not encourage widespread preemptive blackouts.

And three, we have fewer people living in bushfire prone areas around major cities.

But all that might change. Bushfires and other extreme weather events are becoming more common. More people are moving to areas which are either close to the bush, or in coastal towns serviced by long powerlines which go through national parks and state forests. And there is a case for short periods of pre-emptive de-energisation in extreme circumstances to prevent far worse consequences.

Screenshot from the NSW RFS Fires Near Me app on 8 November 2019 showing the fires currently burning on the NSW North Coast

Screenshot from the NSW RFS Fires Near Me app on 8 November 2019 showing the fires currently burning on the NSW North Coast

There is more than one way to respond, though. Undergrounding powerlines is the most obvious—and expensive—long term solutionto bushfire risk. Instead, in eastern Victoria, AusNet has started to take some remote properties in high bushfire risk areas off the grid and onto stand-alone power systems (SAPS). Other rural and regional networks are looking to do likewise.

That is still a relatively expensive solution, and it is not appropriate for whole towns. After the Bushfires Royal Commission, Victoria has been rolling out smart circuit reclosers: “circuit breakers that can quickly stop power flows during a fault and then just as quickly restore it.” But they are not cheap—the pricetag for Victoria alone could be $1 billion—and have their own technical limitations.

The challenge is to increase the resilience of communities and the grid at an affordable cost.

Microgrids—any localised network that can operate in an islanded or offgrid mode when there is an upstream blackout—are another solution. Across California, communities are in various stages of implementing plans to keep the power on even if theirutility declares a PSPS.

What they need in order to do that is enough generation to fill batteries that can then be accessed when the need arises. How much backup power they need depends on what they want to power and for how long. Emergency services and evacuation centres are obviously the highest priority, followed by loads which would suffer the greatest losses, like supermarket freezers.

There is a push in California to mandate a minimum of 25 per cent local energy generation in every discrete community, plus a related amount of battery storage (2kWh of storage for every 1kW of rooftop solar capacity).

Back in Australia, to date microgrids have been seen mainly as a way to shunt power around single owner sites like universities and housing estates, or as solutions to the high cost of powering remote communities.

Networks are starting to think more about what will be required to improve the resilience of rural communities, though. AusNet has just installed a one megawatt-hour battery in Mallacoota, an isolated coastal town in Gippsland ‘at the end of a long radial high voltage line which has been historically susceptible to power outages caused by storms, vegetation and animals.’

Like solar gardens, community scale batteries are a great opportunity not only not only to increase the resilience of local communities, but also to share the benefits of solar energy with households and businesses which cannot install their own solar systems.

Microgrids don’t need to involve a lot of expensive new infrastructure, though. They can link existing rooftop solar systems and home batteries via virtual power plants to service the wider community when there are blackouts up the line.

Going local to increase energy resilience is not a foolproof option. Even a local microgrid can be vulnerable to bushfires under the right (or wrong) circumstances. Having local generation and storage plus the ability to island from the main grid just gives local communities another option when the going gets tough.

Maybe best of all, encouraging local microgrids allows for more widespread upstream de-energisations, reducing the risk of bushfires happening in the first place.

In Australia, one of the things getting in the way of utilising ‘distributed energy resources’ to increase the resilience of local communities is that we don’t currently recognise resilience as an objective in the regulation of the energy system.

We could start by including ‘high impact, low probability’ (HILP) events in reliability standards, which currently exclude ‘major events’. This would allow prudent and efficient network spending to improve local system resilience to be recognised as legitimate by the regulator.

The glitch is that, with only one degree of global heating so far, what were once low probability events are becoming the new normal. Scorching temperatures and howling winds can cause local ‘accidents’ or arson to have deadly consequences.

The regulator is now referring instead to ‘widespread and long duration outages’ (WALDOs) and is considering how to incorporate them into reliability standards.

Waldo may not be your friend, but you may get to hear a lot more of him anyway.