How much capital for renewables is likely to be deployed going forward, and where will it come from?

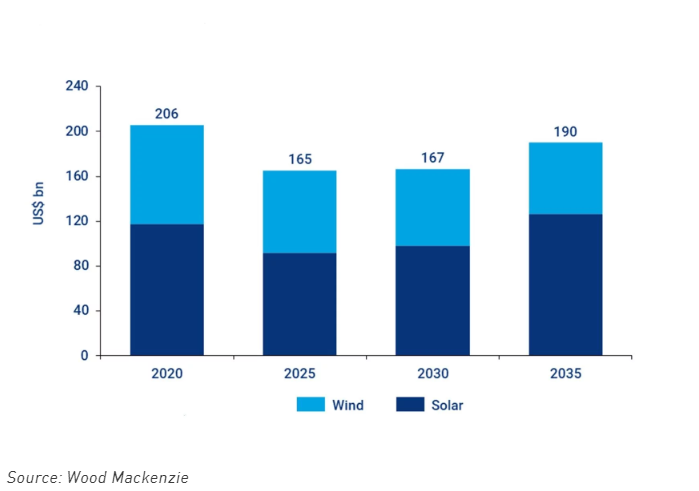

Wood Mackenzie estimates that the combined global capex spend on wind and solar projects will range from around $165 billion to $190 billion a year between 2020 and 2035. That calculation is based on realistic growth scenarios as well as project development at a global average cost of around $1.00 per watt for onshore wind and solar.

Capex Outlook for Wind and Solar, 2020-2035

Consistency in capital deployment

There are significant variations in project development costs by country, as shared in a recent Wood Mackenzie presentation on the topic in Paris.

For example, solar projects can be developed for $0.40 per watt in Spain or Portugal, compared to $1.50 per watt in Japan. However, the global average is around $1.00 per watt for onshore wind and solar and $2.00 per watt for offshore wind. This translates to capital deployment of around $190 billion in 2019.

Over the short term, this will decline slightly, falling to $160 billion by 2025. This is due to the combined impact of policy changes around the world and ongoing reductions in equipment costs.

After 2025, the total capex spend will start growing again. It is expected to hit $190 billion by 2035 as cheaper unit economics and favorable regulatory changes make new markets more attractive.

How investors should perceive renewable energy generation assets

One way to quickly evaluate risk is to consider debt financing and leverage rates available from large banks.

An onshore wind or utility-scale solar PV project can currently be financed with 75 to 85 percent of leverage at 100-130 basis points over LIBOR (for investments in BBB credit-rated countries). This is very close to the lending rate a large bank would provide for a highway or an airport.

So in many cases, these assets are bankable, investable and considered to be comparable to other high-quality investment opportunities on the risk-return curve.

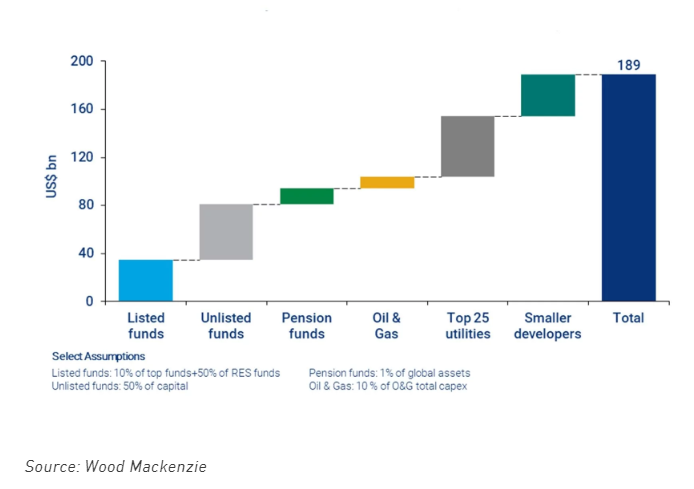

What type of firms will deploy capital in renewables?

Due to the de-risked nature of wind and solar power generation as an asset class, unlisted and listed funds currently deploy around 45 percent of the $190 billion spend.

Utilities, which are legacy players in the power generation value chain, come next with roughly 25 percent of the annual spend. Pension funds and oil and gas companies, relative newcomers to this asset class, deploy 3 to 6 percent each.

The fragmented nature of utility-scale development in many countries, such as Germany, the Netherlands and parts of Spain, means that small developers also maintain a meaningful share (18 percent).

Sources of Capital Deployed in Renewables in 2019

How will this change over time?

A significant share of capacity (100 to 120 gigawatts out of 170 gigawatts) is still expected to be awarded under fixed remuneration auctions through 2030. The role of passive and low-WACC investors, such as pension funds, is likely to increase over the long term as a result.

Even a 1 percent increase in pension capital could provide an additional $15 billion to $20 billion for renewable energy projects. As countries scale their auction plans, small developers are likely to consolidate their portfolios. Their share would decline.

Large oil and gas companies, eager to join the energy transition, are likely to increase their allocation to 10 to 15 percent of their annual capex plans. Galp Energia, for example, made this commitment in October 2019.

Oil and gas players are also likely to have the appetite to pursue higher-risk opportunities to meet shareholder return targets. This might include emerging market project development, distributed generation and behind-the-meter generation.

Utilities will likely maintain their share at 25 percent. It remains to be seen whether large utilities will spread their capex across a variety of opportunities or focus on specific technologies or activities.

Ongoing transformation plans of prominent utilities suggest that there is not a one-size-fits-all model. Many are trying to focus on niches that capitalize on their unique competitive advantages.

The impact of merchant models

A move from fixed remuneration to merchant models would expose assets to power-price volatility. Passive sources of capital would find it more difficult to deploy capital in fully merchant or unhedged projects.

However, over the next five to 10 years, new hedging instruments are likely to become more robust and liquid, allowing asset owners to continue to deploy capital in a flexible way. So the transition to merchant assets is a short-term headwind for an asset class with a long-term tailwind.

The emissions story: A grim outlook

The capex pool expected to emerge from the power generation sector might seem significant. But $165 billion to $190 billion per year for wind and solar does not bring the world close to the 2 degree target agreed upon in Paris in 2015.

Swapping the world’s entire coal power plant fleet by 2030 would require a hypothetical additional spend of $200 billion a year. This highly optimistic scenario would significantly step up efforts toward a cleaner and emissions-free world but would only contribute an additional 13 percent toward the global Paris target (including non-power-sector emissions).

Far more needs to be done to help cut back from 51 billion tons of CO2 to 35 billion tons by 2050.

These calculations focus only on renewable energy generation. The other side of the story is the additional investment needed in transmission, energy storage and other areas that complement growth in renewables. If the U.S. market is an example, the investment requirement could more than double, depending on the technology choices made.