America’s coal-burning power plants are shutting down at a rapid pace, forcing electric utilities to face the next big climate question: Embrace natural gas, or shift aggressively to renewable energy?

Some large utilities, including Xcel Energy in the Upper Midwest, are now planning to sharply cut their coal and gas use in favor of clean and abundant wind and solar power, which have steadily fallen in cost. But in the Southeast and other regions, natural gas continues to dominate, because of its reliability and low prices driven by the fracking boom. Nationwide, energy companies plan to add at least 150 new gas plants and thousands of miles of pipelines in the years ahead.

A rush to build gas-fired plants, even though they emit only half as much carbon pollution as coal, has the potential to lock in decades of new fossil-fuel use right as scientists say emissions need to fall drastically by midcentury to avert the worst impacts of global warming.

“Gas infrastructure that’s built today is going to be with us for 30 years,” said Daniel Cohan, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Rice University.

“But if you look at scenarios that take climate change seriously, that say we need to get to net zero emissions by 2050,” he said, “that’s not going to be compatible with gas plants that don’t capture their carbon.”

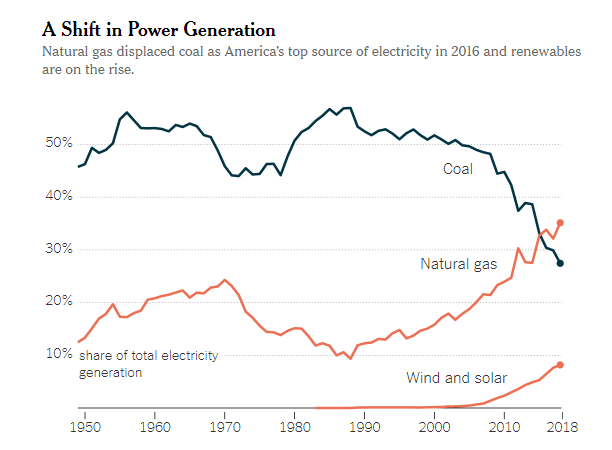

Totals do not add up to 100 percent. Other sources of generation are not shown. Source. U.S. Energy Information Administration | By The New York Times

Totals do not add up to 100 percent. Other sources of generation are not shown. Source. U.S. Energy Information Administration | By The New York Times

In some states, policymakers are now pushing to leave gas behind to meet ambitious climate goals. Last week, New York lawmakers passed a sweeping energy bill that calls for the state to switch to entirely carbon-free electricity sources by 2040, following states like California and New Mexico that have passed similar laws.

Since 2005, most power companies have lowered their carbon dioxide emissions significantly, in large part by shifting from coal to gas. Coal plants have become uncompetitive with other kinds of energy generation in much of the country, despite the Trump administration’s efforts to save them by rolling back federal pollution regulations.

But in a recent analysis, David Pomerantz, the executive director of the Energy and Policy Institute, a pro-renewables group, looked at the long-term plans of the 22 biggest investor-owned utilities. Some in the Midwest are planning to speed up the rate at which they cut emissions between now and 2030. But other large utilities, like Duke Energy and American Electric Power, expect to reduce their carbon emissions at a slower pace over the next decade than they had over the previous decade.

“I really think gas is at the crux of it,” Mr. Pomerantz said. “You’ve got some utilities looking at gas and saying, ‘No thanks, we think there’s a cleaner and cheaper path.’ But then you’ve got others going all-in on gas.”