Key findings

Given that new nuclear projects have faced significant construction delays and cost overruns, France’s plan to build 14 new reactors by 2050 is unrealistic.

Nuclear should continue playing a key role in France’s power sector but not at the expense of renewables growth.

French policy has recently shifted from a commitment to reduce nuclear generation to calls for a “renaissance” of the technology.

France’s heavy reliance on nuclear has kept its power sector emissions relatively low but left it exposed to the many challenges associated with the technology.

Energy security

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the subsequent sharp reduction of Russian pipeline gas supply to Europe, spot power prices in the continent skyrocketed and affected industrial and retail consumers dearly. Prices peaked in August 2022 and remained historically high until 2023. Prices are now back to pre-2022 levels.

In the last two years, Europe’s imports of Russian piped gas have been largely replaced by liquified natural gas (LNG) from alternative sources. Curtailments and demand response mechanisms have contributed to absorbing the price shock. European Union consumers have shown much resilience in their ability to reduce energy consumption. Russia’s share of EU gas imports has fallen from 40% in 2021 to less than 15% now (including pipe and LNG supplies).

In the case of France, this energy crisis was especially challenging since it coincided with many nuclear reactors being taken offline for maintenance work. In 2022, the country was a net power importer for the first time in more than 40 years. In 2023, as most nuclear reactors went back online, it resumed being a net power exporter. The episode illustrated the risks of France’s exposure to nuclear power.

Nuclear has dominated France’s power mix since the 1980s

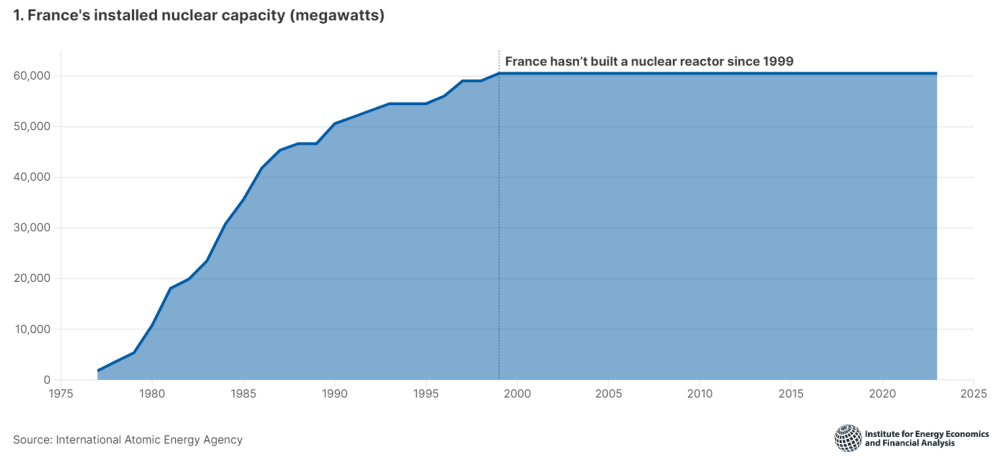

France’s development of nuclear plants started in the 1970s, partly in response to the 1973 OPEC oil embargo. Nuclear power was seen as a way of ensuring the country’s energy independence. The first plant was commissioned in 1977. New units were then added to the system on an almost-annual basis until 1999 (see Chart 1).

During this period, France’s nuclear capacity reached 61.5 gigawatts (GW). This translates into an average of 400 terawatt-hours (TWh) of production per year, or 70% to 80% of the country’s total power generation, depending on the year. France has the highest share of nuclear in its generation mix in the world and is second only to the U.S. in terms of installed capacity. Added to its 25GW of hydropower capacity, the two technologies can average 90% of France’s base and peak electricity demand, CO2-free.

France has also developed an industry to export its nuclear reactors. The latest technology, the European Pressurised Reactor (EPR), has been delivered to Finland, China and the UK.

However, as Chart 1 shows, France hasn’t built a nuclear reactor since 1999, meaning its EPR expertise hasn’t benefitted its domestic nuclear fleet as much as it could have. Construction of the latest reactor, Flamanville 3, started in 2007. It has yet to be commissioned. So far, it is delayed by 12 years and is almost four times over budget.

With many reactors reaching the end of their 40-year lifetime, decision-makers must choose whether to shut them down or extend their operations by 10 or 20 years through major refitting programmes.

Policy shift sees France plan a “nuclear renaissance”

Nuclear’s role in France’s future power mix has become an increasingly crucial and controversial political debate.

After his election to the presidency in 2012, François Hollande committed to reducing the share of nuclear in France’s power production to 50% by 2035, with an ambitious decommissioning plan. However, not one nuclear unit was decommissioned under his presidency and no legally binding decommissioning dates for plants were set. The only binding commitment was to cap French nuclear capacity to 63GW.

During his first term between 2017 and 2022, President Emmanuel Macron did not engage in any nuclear policy shift, postponing the debate. The Flamanville 1 and 2 nuclear reactors were decommissioned in 2020 because they had exceeded their 40-year lifetime and no agreement had been made with operator EDF for a major refit programme.

Criticisms

During his second term, Macron has called for a “nuclear renaissance” and announced a goal to build 14 new reactors by 2050, implicitly targeting a maintenance of the 63GW of capacity and nuclear’s share in the power generation mix. The announcement was heavily criticised from across the political spectrum, with the main argument being that nuclear would slow the growth of renewables. Concerns have also been raised about the challenges associated with nuclear technology such as safety issues, long construction times, massive capital expenditures (see Chart 2), a levelised cost of electricity higher than renewables and waste management.

Despite its role in reducing carbon emissions, Nuclear must not limit Renewables growth

It is undeniable that nuclear has helped France’s power sector emissions to be relatively low. Emissions are the fifth-lowest in Europe at 53.5g of CO2 per kilowatt-hour, behind only countries whose electricity mixes are dominated by hydropower: Iceland, Switzerland, Sweden and Norway. The emissions intensity of France’s power sector is 10 times lower than Germany’s and 15 times lower than Poland’s (see Chart 3).

Nuclear is not considered a renewable technology since uranium is needed, but the debate remains open on whether nuclear is green. The clear advantage of the technology is to provide stable, CO2-free baseload generation for a long operational lifetime.

Although its challenges are well known (e.g., safety, costs, waste management), the French plan to build 14 new nuclear units by 2050 seems at best unrealistic.

Significant construction delays and cost overruns faced by the two latest EPRs, Flamanville 3 in France and Olkiluoto 3 in Finland, are evidence that building an average of one reactor every two years until 2050 is not a feasible goal.

Nuclear should certainly continue playing a key role in France to alleviate the climate crisis but not while disadvantaging the growth of renewables.

Six new reactors between now and 2050 is realistic

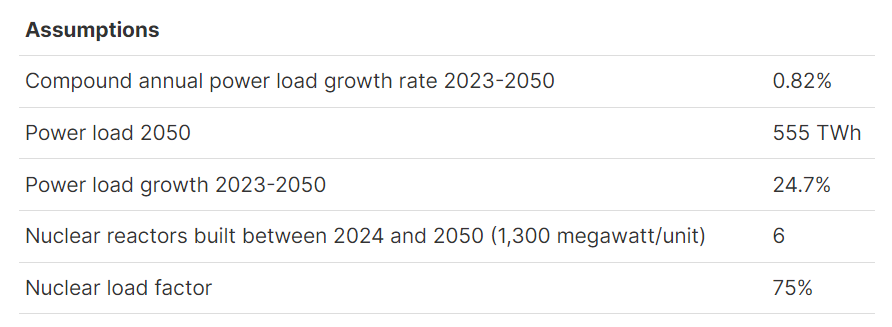

The following assumptions establish the conditions to assess nuclear’s share in France’s power mix in 2050:

Assuming the parameters above (six reactors built between 2024 and 2050 seems a reasonable estimate considering the lead time required for Flamanville 3 and Olkiluoto 3), 13 of the 56 currently operational nuclear reactors would need to have their lifetime extended by 20 years to reach a share of 30% nuclear in the electricity mix. To reach 40%, 20 reactors would need to have their lifetime extended by 20 years. So far, no agreement has been met between the government, the French Nuclear Safety Authority and plant operator EDF to set up a lifetime extension refit programme.

Therefore, in IEEFA’s view and based on the assumptions above, nuclear’s share in France’s 2050 mix could be a maximum of 40% and more realistically 30%, complemented by onshore and offshore wind, solar, biomass and tidal energy.