Wivenhoe power station. Source: Queensland Mining & Energy Bulletin

Wivenhoe power station. Source: Queensland Mining & Energy Bulletin

Australia has three pumped storage hydro schemes.

Talbingo (sometimes called T3), which forms part of the Snowy scheme, is the oldest, and largest, completed in 1974. It now has a total capacity of 1,800 MW and a pumping capacity of about half that.

The Shoalhaven scheme, also in New South Wales and completed a few years later, has a capacity of 240 MW, and was designed to function as both pumped storage for electricity and as a standalone pump to operate as part of the water supply to metropolitan Sydney.

Wivenhoe, near Brisbane, is a “pure” pumped hydro scheme with a total capacity of 500 MW. It was completed in 1984 and operates within the Queensland region of the NEM.

As can be deduced for the completion dates, all three of these schemes were built by the relevant publicly owned electricity generation and transmission authorities (respectively, the Snowy Mountains Authority, the Electricity Commission of New South Wales (Elcom) and the Queensland Electricity Commission (QEC).

The schemes were intended to operate on a daily cycle, pumping overnight when demand was low, and generating during the morning and evening peak periods.

To put it another way, they were intended to create so-called base load, thereby smoothing out demand on the New South Wales and Queensland coal fired power stations, reducing the need for them to ramp up and down to meet demand.

Coal fired steam generation is not a technology well suited to frequent ramping, which increases fuel consumption per unit of output and also increase maintenance costs, all else being equal. At the time the pumped storage systems were built there were no gas fired peaking plants in either state.

Corporatisation of the various supply authorities during the 1990s, requiring them to operate like profit maximising businesses, was followed by the establishment of the National Electricity Market, the completion in 2001 of the major inter-connector between Queensland and New South Wales, and the construction of gas fired peaking power stations.

The combination of these changes fundamentally modified the economic and technical environment within which these three schemes operated.

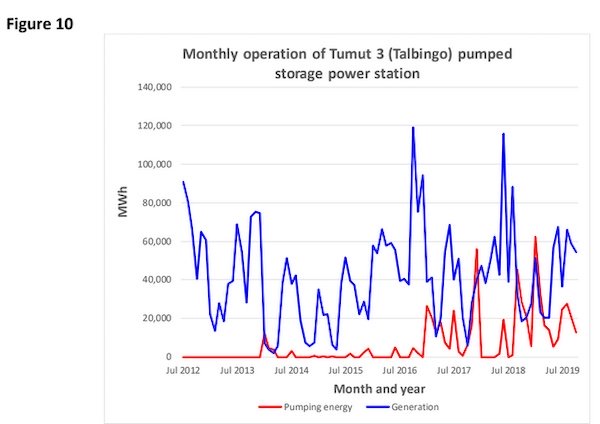

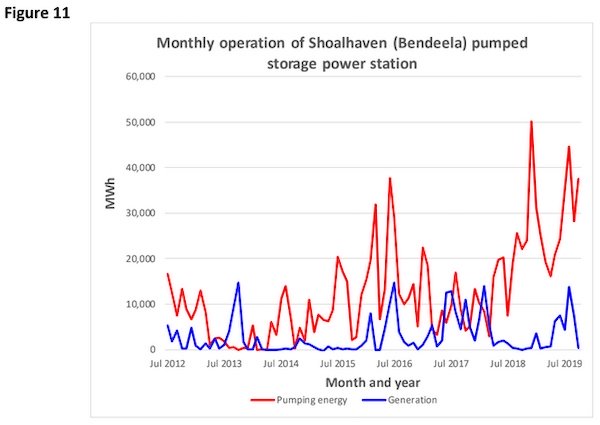

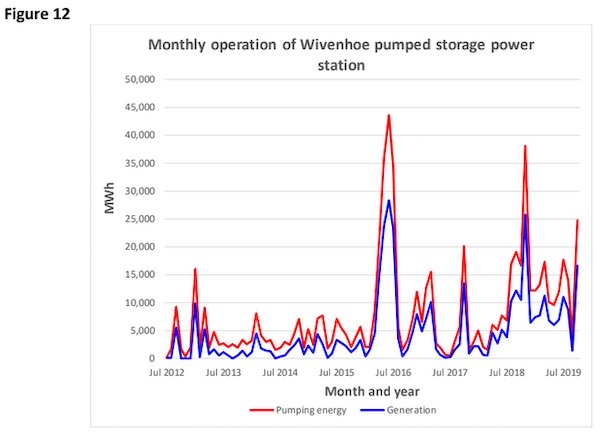

Figures 10, 11 and 12 show how Talbingo, Shoalhaven and Wivenhoe, respectively, have been used over the past seven years.

For a long time, Talbingo, owned and operated by Snowy Hydro, did virtually no pumping, and thus no energy storage, meaning that it operated mainly as a conventional power station, using water coming down the Tumut River from T2 power station to generate.

At Shoalhaven, which is owned by Origin Energy, one of the big three gen-tailers, the excess of pumping over generation has arisen because of extensive use to supply water to Sydney.

Wivenhoe is the only “pure” pumped hydro scheme of the three. Until the end of October Wivenhoe was owned by CS Energy, one of the two large state government owned electricity generation businesses, with a large portfolio of coal fired power stations.

Like Talbingo, until very recently Wivenhoe was not often used, presumably because it was more profitable for CS Energy to supply directly from its power stations.

Given that the round trip efficiency of Wivenhoe is only around 65%, not using it to store coal generated electricity is in fact a lower emission choice, though probably often not a lower cost choice for electricity consumers, since it could add competition to the Queensland wholesale market.

When it was used, pumping occurred overnight and generation occurred during the evening peak, after solar generation has fallen away.

This mode of operation, though not the frequency of use, began to change, around April this year, as the rapid growth of solar generation has seen Queensland spot prices often reach their daily minimum in the middle of the day, rather than the traditional slot of the middle of the night, particularly during the spring and summer months.

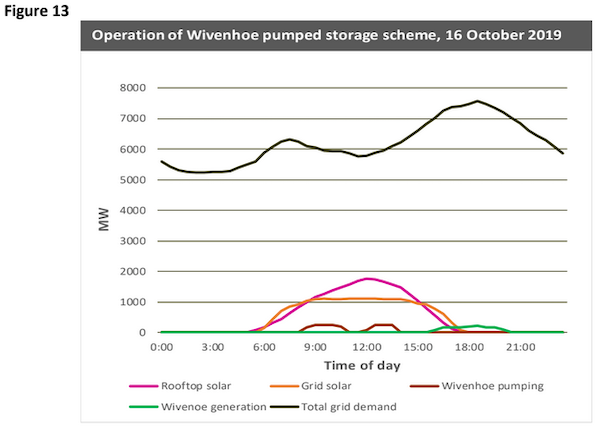

For example, Figure 13 graphs the operation of Wivenhoe on Wednesday 16 October 2019. The pumps used about 930 MWh in the middle of the day, when solar generation was at its peak, and the power station supplied about 710 MWh over four hours in the late afternoon and early evening.

The balance of pumping and generation on this particular day suggests a small excess of water volume discharged through the generators over water volume pumped.

Over the whole day, total supply from grid and rooftop solar together was over 22,000 MWh, so only a small proportion was time shifted by Wivenhoe. However, this is sufficient to demonstrate the valuable contribution which pumped storage can make to the efficient overall operation of the electricity supply system.

On 1 November ownership of Wivenhoe was transferred from CS Energy to the new CleanCo, the state government owned business established to take an active role in the sustainable transition of electricity supply in Queensland.

It is expected, given the increasingly common occurrence of negative prices during the middle of the day in the Queensland wholesale market, as well as the new ownership, that from now on Wivenhoe will be used much more frequently, and will be storing solar rather than coal generated electricity.

Origin has been operating the Shoalhaven scheme in a similar way to Wivenhoe for most of the past two to three years. The company is currently completing a detailed feasibility study, supported by ARENA, to build a new underground generator, which will almost double the scheme’s generation capacity. Energy storage capacity will be unchanged.

The operating options possible for Shoalhaven and, even more, Wivenhoe, are constrained by the limited capacity of their respective upper level reservoirs. Neither scheme would be able to store energy in quantities to make a material contribution to balancing supply with demand over more prolonged periods than a few hours, such as will be required during periods of prolonged cloudy or windless weather.

By contrast, Snowy Hydro has mainly been using Talbingo by pumping on some days and generating on others.

It has much larger storage capacity in Talbingo Dam, and also much larger generating capacity at T3 power station, making it better able to meet longer term requirements. During the past two summers it did this by partly holding back water during spring to maximise the volume available should large quantities of generation be required during extreme peak periods.

During the week from 6 February 2017, T3 power station played a crucial role by generating at its near maximum capacity of around 1,700 MW for more than three hours.

This meant that it effectively supplied all the electricity it was able to do, starting with Talbingo Dam at full supply level. Without this contribution, many New South Wales electricity consumers would have experienced load shedding on Friday 10 February 2017.

The overall operation of Snowy Hydro, as a business, is particularly complex. It is a retailer, with the fourth largest market shares in both New South Wales and Victoria.

It is a generator with a dominant role in meeting peak demand in the NEM and, contractually, providing capacity contracts to other retailers and large consumers.

Its hydro generation options are constrained by legal obligations to deliver water into the Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers at specified times in specified volumes. It is seeking to build a very large new pumped storage scheme, in the form of Snowy 2.0, with roughly ten times the energy storage capacity of Talbingo.

If it proceeds, Snowy 2.0 will be Australia’s largest single investment in electricity supply infrastructure for many years. There are, however, reasons to ask whether it will offer the best return on investment of all the possible options for moving forward at this stage of Australia’s electricity system transition, as it is currently expected to progress.

The owners of most of the currently operating coal fired power stations plan to keep them in operation over the next 10 to 15 years, during which time they should be well capable of supplying demand for electricity during extended periods of low wind and solar generation.

At this time, a number of smaller pumped hydro schemes, designed to operate on a daily cycle and located closer to major centres of demand and/or renewable generation, may well provide a more effective, lower cost option.

A further drawback of Snowy 2.0 is that it will require an additional investment of several billion dollars in new transmission capacity, lining the scheme to the New South Wales and Victorian grid.

Snowy Hydro has argued that this additional interconnector capacity is needed anyway, so should not be seen as part of the Snowy 2.0 investment.

While there is no argument with the need for new capacity, AEMO, and many other parties, have concluded that a much higher priority is to increase capacity much further west, where it would also link with the proposed new Riverlink interconnector between New South Wales and Victoria.

This project is strongly supported by the state governments, as well as AEMO, and is likely to be completed well before Snowy 2.0 could be operational.

Snowy Hydro is now fully owned by the Commonwealth government. It will be very interesting to see how Snowy Hydro uses Talbingo over the next few years, as it seeks to advance Snowy 2.0.