He explains how greater industry collaboration, the upskilling of energy workers, and the repurposing of legacy assets can lower the cost of renewable infrastructure and create long-term energy and job security.

Back in 2015, America planted the seeds for a future powered by clean energy when its first commercial offshore wind farm was constructed off the coast of Long Island.1 In the year 2023, the wind farm, Block Island, began to deliver power. Following years of regulatory scrutiny and strategic planning, it is now a live example that thousands of megawatts can be generated from clean sources.

The project includes 12 turbines and is the perfect example of an international and collaborative approach as it is a joint venture between Denmark’s Orsted and a New England-based utility company, Eversource. It promises to generate enough power for around 70,000 homes at full capacity, a drop in the ocean when it comes to meeting America’s energy needs. However, it is considered a major milestone. It was launched as a pilot project with the aim of demonstrating that offshore wind is viable in the United States, and it has done just that.

The nation has the technical skills, manufacturing capabilities and investment required to grow a thriving domestic clean energy sector. However, a global supply chain underpinning it and support from existing sectors will allow the country to accelerate plans for a low-carbon future.

A wave of offshore wind projects hits America

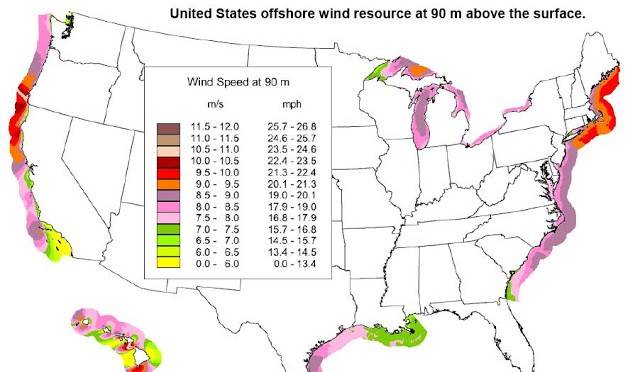

A report published this year by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), an organisation backed by the US Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Wind Energy Technologies Office, found that a total of 4,097 MW of offshore wind energy was under construction as of May 2024.2 That is four times the volume recorded in NREL’s previous report. The pipeline of offshore wind projects totals a capacity of 80,523 MW, up 53% since 2023.

Historically, the US floating offshore wind market, which requires turbines to be moored to the seafloor in deeper waters instead of being fixed to a foundation, has experienced slower growth. That said, in April 2024, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) published a leasing plan through to 2028.3 This means that 12 offshore wind energy auctions, seven of which are in deep water and suited for floating offshore wind installations, will go ahead.

This is an important development because floating offshore wind can be deployed in areas where it is not practical to install traditional wind turbines. Floating wind turbines tend to be able to take advantage of more favourable wind conditions; they can potentially access higher wind speeds, generate more electricity, and have less impact on the environment as they are located further from shore. This means they have less impact on marine life, and their anchoring solutions create less noise pollution.

However, the same NREL report warns that as the floating offshore wind market has not yet matured in the US, the country’s floating wind technologies are not ready for ultradeep waters. Testing and demonstration are crucial, as is learning key lessons on viable techniques and technologies by looking at international markets that have established successful floating offshore wind projects.

Globally, floating offshore wind has exploded; 245MW of floating offshore wind is currently operational across 15 counties.4 Norway leads with 94MW of capacity across three projects, shortly followed by the United Kingdom with 78MW of capacity over two projects. China, Portugal and Japan have operational capacities of 40MW, 25MW, and 5MW, respectively.

The US, through BOEM, already works closely with regulators in Denmark, Germany, and the UK to share key technical knowledge and environmental considerations, and this will need to continue if America is to realise the full potential of offshore floating wind.

The importance of cross-pollination

There are multiple states in the US that have an established offshore oil and gas industry. This means a highly skilled and experienced workforce, tried and tested technologies and processes, manufacturing capabilities, and a well-connected supply chain, including fleets of ships designed to aid offshore operations and well-configured ports, are all ready to be mobilised.

A great example of this is Louisiana. The foundations for the Block Island Wind Farm were designed and built in the state, while a group of technical specialists from Louisiana-based companies provided engineering expertise, shipping services, and marine welding support to get it ready.5The wind farm developers recognised that Louisiana is a hotbed of technical innovation and is home to thousands of skilled workers due to its rich oil and gas heritage. The state handled over 60% of America’s liquefied natural gas exports of 2023, and oil and gas operations support about one in nine jobs in Louisiana.

Offering local people the opportunity to diversify their skills by supporting the burgeoning renewables sector, as well as oil and gas, provides a sustainable route to paid work for the future whilst plugging a growing skills gap.

Around 1.1 million workers are needed to build wind and solar plants around the world, according to recent reports.6 A further 1.7 million skilled workers are required to operate and maintain the renewables infrastructure. As a result, the NREL estimates that the US offshore wind industry will need to hire between 15,000 and 58,000 full-time workers each year from 2024 to 2030.7However, there has already been a noticeable shift in American energy workers refocusing on renewables. According to the DOE, the creation of clean energy-specific roles across every state grew by 3.9% up until 2022.8 Data published by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) shows that clean energy jobs grew by 200% in 2023 compared to job growth economy-wide.9It also claims that renewable energy-focused jobs now make up 40% of the 8.35 million people employed in the energy industry across America, which demonstrates that the renewables sector can play a key role in lowering US unemployment rates if this trend continues.

A talent gap, however, could significantly delay clean energy projects on American soil. The NREL has recommended that efforts should be made to attract and train tradespeople who have offshore experience and currently operate in oil and gas.10 They represent a pool of talent with transferable skills prime for supporting offshore wind projects.

The NREL also encourage greater collaboration between US industry stakeholders and global, national, regional, and state partners on major workforce challenges through key working groups. It is simply not enough to create jobs for local people. They will require continuous training to stay ahead of changing regulatory requirements, new advancements in technologies, and a broader understanding of international standards and equipment for offshore wind.

This is important as many offshore wind structures in America will need to include parts from Europe as the nation’s manufacturing capability catches up with more mature markets. For example, the Block Island Wind Farm features monopiles made in Spain, a 450-ton generator from France, and blades from Denmark.

America’s workforce, which rode the oil and gas boom, now has an opportunity to secure a future career in renewable energy by upskilling their knowledge and learning about manufacturing techniques and design codes developed in European countries that have a 20-year head start.

Furthermore, the industry will look to those individuals to create new processes and drive the advancement of homegrown innovations for the benefit of the country’s clean energy sector, and their own prosperity. This cross-pollination will play a critical role in accelerating the renewables projects that have already been granted licenses, and any others to follow.

Oil and gas can accelerate clean energy goals

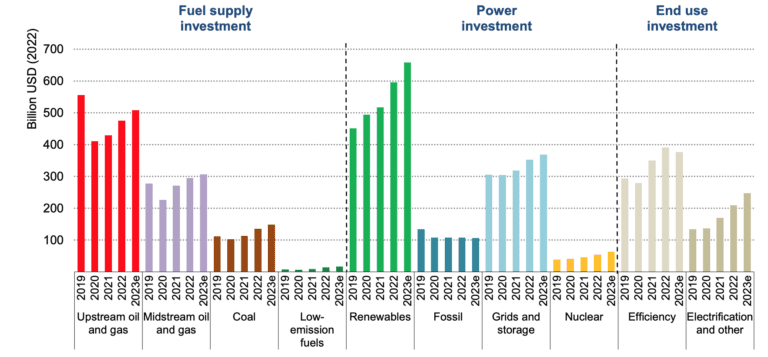

The oil and gas industry has already invested billions into clean energy projects to help drive low and zero-carbon technologies. We are witnessing a fundamental shift in how global oil and gas operators invest as they face mounting pressure to meet carbon-reduction targets. As they diversify their portfolios, synergies emerge between both the oil and gas and renewables sectors.

Skilled workers, vessels, and technologies traditionally focused on oil and gas can be seamlessly refocused on renewables projects when available, which means less downtime and significant cost savings for both sectors.

Furthermore, existing oil and gas assets can be repurposed to support both sectors as they have fluctuating needs over time. Decommissioning was once considered the answer to removing ageing assets, but it is costly and comes with major environmental risks. Therefore, oil and gas operators are more likely to opt to repurpose their assets to accelerate clean energy projects.

According to an academic report, it has been estimated that approximately one-third of the total life costs (operation, maintenance, and service costs) of an offshore wind project can be reduced if the oil and gas sector is involved, the key being to repurpose key assets such as rigs and support vessels.11 The sector is therefore playing a key role in driving progress in the renewables sector forward.

Included in the report is the example of electrifying oil and gas offshore operations by installing wind farms, which can also mean floating turbines. This would reduce the need to operate diesel or gas generators on the platform, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants. Furthermore, the report recommends the use of oil and gas platforms as bases for wind farms.

There are significant cost savings on offer when electrifying platforms as it lowers operating costs, and it also improves safety by reducing the risk of on-platform ignitions. It also reduces noise and vibrations to protect marine life, as well as lowering emissions.

Another key point is that a rise in offshore wind installations will make it possible to produce green hydrogen at scale, which requires electricity generated by wind turbines to split water into hydrogen and oxygen through the process of electrolysis. The US has already started work on this form of clean energy.

In 2021, the DOE announced the Hydrogen Shot, which aims to reduce the cost of clean hydrogen by 80% to $1 per 1 kilogram in a decade.12 Following that, in 2023, the organisation Hy2gen USA launched a project to identify, evaluate, and develop favourable locations to power renewable hydrogen and e-fuel production from gigawatt-scale offshore wind energy, mainly in the US.13The digital era requires a wider energy mix

According to the International Energy Agency, we have entered a ‘new age of electricity’ as nations around the world use more air conditioning, switch to electric vehicles (EVs), and build new data centres in response to the evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) and other innovations such as digital twins.14AI and digital twins can support the maintenance and the long-term integrity of offshore assets such as rigs or floating wind platforms, so it’s important for the industry that these innovations continue to evolve.

In the first half of 2024, new data centres totalling nearly 24GW were planned to be built in the US, which is more than triple the same period last year and already exceeding the entirety of 2023.15 The oil and gas industry alone won’t be able to keep up with the energy demands of this digital revolution.

Instead, a mix of fossil fuels and renewables is most likely going to power the data centres in the near term as they rapidly expand nationwide. At this time, the US government is going through a period of change, and what lies on the horizon of America’s offshore wind sector remains clouded. However, it is clear that the foundations have already been laid for the offshore wind sector to flourish.

America has proven it can work with international counterparts to share best practices and drive technical innovation, but it will take a renewed collaborative approach across the energy sector and globally to take the US wind sector to the next level.

About the author

Rob Langford is the Vice President of Global Offshore Renewables at ABS, bringing over 30 years of extensive experience in offshore consulting, engineering, construction, installation, operations and maintenance.

With a deep understanding of offshore developments, Rob offers a comprehensive global perspective on both New Energy and Hydrocarbons. His roles at prominent companies such as Worley, SBM Offshore, Shell, Fluor, and Wood have equipped him with the expertise to successfully lead numerous offshore projects around the world.

Rob’s collaborative approach in leadership offshore fixed and floating projects has consistently added value for leading energy companies around the world. He holds a degree in Mechanical and Production Engineering from Anglia Ruskin University.