The Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is teaming up with Bridgestone, one of the world’s largest tire makers, to scale up a chemical process that converts ethanol into butadiene—synthetic rubber’s most important ingredient.

At the center of the collaboration sits a catalyst developed by PNNL researchers that cuts out the need for heat and reduces the carbon dioxide emissions of current butadiene production.

While other ethanol-to-butadiene catalysts exist, “this catalyst demonstrates high selectivity at high conversion, which means it generates lots of butadiene without losing its performance with time,” said Vanessa Dagle, a chief scientist at PNNL and manager of the project.

Butadiene demand is rising

Traditionally, butadiene is created as a by-product of a process called steam cracking. In a refinery, crude oil (made of long chains of hydrocarbon molecules) is heated and combined with steam to destroy chemical bonds and create smaller hydrocarbons. Further refinement of the smaller hydrocarbons produces ingredients needed for plastic food packaging, synthetic fabrics, fuel for cars, trucks, and airplanes and rubber tires.

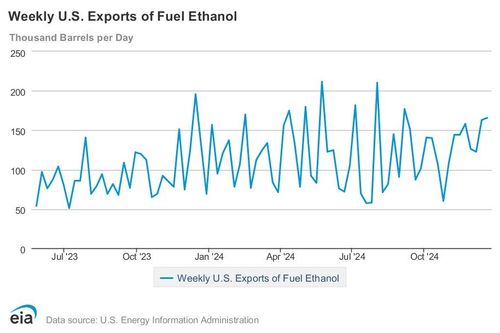

But butadiene production has run into some barriers. Rubber demand is rising, which means the world needs more butadiene. Simultaneously, North America is shifting more toward extracting natural gas from shale rather than crude oil. Steam cracking crude oil products like naphtha creates a large fraction of butadiene compared to steam cracking natural gas, so as nations switch to extracting natural gas, less butadiene can be produced. Because of this shift, researchers have been searching for new ways to make butadiene, Dagle said.

“Projects like this will help advance the science and technologies necessary to make the industry more sustainable, placing our engineers and scientists at the forefront of potentially revolutionizing how tire makers obtain butadiene in a more nature-positive way,” said Mark Smale, Bridgestone Executive Director of Core Polymer Science. “We are very excited about this project and the innovative new process, and very appreciative of PNNL’s partnership.”

PNNL researchers first developed the catalyst in 2018, which was further advanced through a Technology Commercialization Fund Project supported by DOE’s Bioenergy Technologies Office. Now, with over $10 million in funding from DOE’s Industrial Efficiency and Decarbonization Office, Bridgestone and PNNL will spend three years perfecting the catalysis process.

Sustainable, circular economy

By using ethanol, researchers hope to make butadiene production more sustainable. For one, producing ethanol doesn’t require starting with crude oil. What’s more, ethanol comes from plant matter, and researchers are also looking at ways to produce ethanol from society’s waste. Nearly all of the country’s ethanol currently comes from the starch in corn grain, but ethanol can also be produced from other types of biomass, like algae and food scraps. Researchers have also explored using human waste (in the form of wastewater treatment sludge) and industrial wastes as ethanol feedstocks. Even rubber tires can be recycled to produce ethanol.

When it’s mixed with ethanol, the catalyst works by first breaking off ethanol’s hydrogen atoms, which creates acetaldehyde (a compound that occurs naturally in coffee, ripe fruit and bread). Further reactions continue to rearrange atoms and bonds until butadiene forms.

“With PNNL’s catalyst, we can turn society’s trash into valuable raw materials for a multitude of products we use daily while reducing greenhouse gas emissions,” Dagle said.

During the three-year collaboration, Bridgestone will supply PNNL with ethanol from recycled tires. With that ethanol, PNNL researchers will work to produce a catalysis process that can be scaled up from the lab scale to a commercial scale.

Eventually, “we'll have a catalyst and process ready to go for their pilot plant,” said Rob Dagle, co-principal investigator and senior research engineer at PNNL. Bridgestone plans to build the pilot plant in Akron, Ohio.

By the time the pilot study ends, researchers hope the process will be ready for commercialization.

“If the pilot study goes well and it goes to commercialization, we'll have green tires in the future,” Vanessa Dagle said.