According to the Department of Energy, offshore wind has the potential to generate more than 2,000 GW of capacity per year, nearly double the nation's current electricity use. Even if only 1% of that potential is captured, nearly 6.5 million homes could be powered by offshore wind energy within the next decade.

Today states along the Eastern Seaboard, from Maine to Virginia, are poised to join a renewable-energy revolution that will not only provide clean, green electricity but also create tens of thousands of jobs, revitalize distressed port cities and spur economic growth in dozens of coastal communities.

"We are in an incredible growth period," said Laura Morton, a senior director at the American Wind Energy Association in Washington, D.C. She cited a recent white paper from the Special Initiative for Offshore Wind that projects a $70 billion business pipeline in the U.S. by 2030.

A study co-authored by New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and the Clean Energy States Alliance found that developing 8,000 MW of offshore wind from Maryland to Maine by 2030 could create up to 36,000 full-time U.S. jobs. What's more, said Morton, "to build and operate an offshore wind farm requires a diverse workforce of 74 different occupations," from engineers to pipefitters.

GE's giant wind turbine

Following the scalability path blazed by offshore wind projects in Northern Europe — which now has a total installed capacity of 18,499 MW across 11 countries — the stars are aligned for the U.S. industry. Costs have come down, technology has gone up, states have mandated ambitious renewable-energy goals, and the federal government has leased 15 commercial ocean sites for $472 million. Public sentiment also is high to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, especially as climate change keeps accelerating.

“Costs have been reduced by about 17% in the U.S. over the last five years,” said Thomas Brostrom, U.S. CEO of Orsted, a Danish energy company specializing in offshore wind and a partner in several stateside projects. The megawatt-per-hour rates for projects are at a level very competitive with other energy sources, he said.

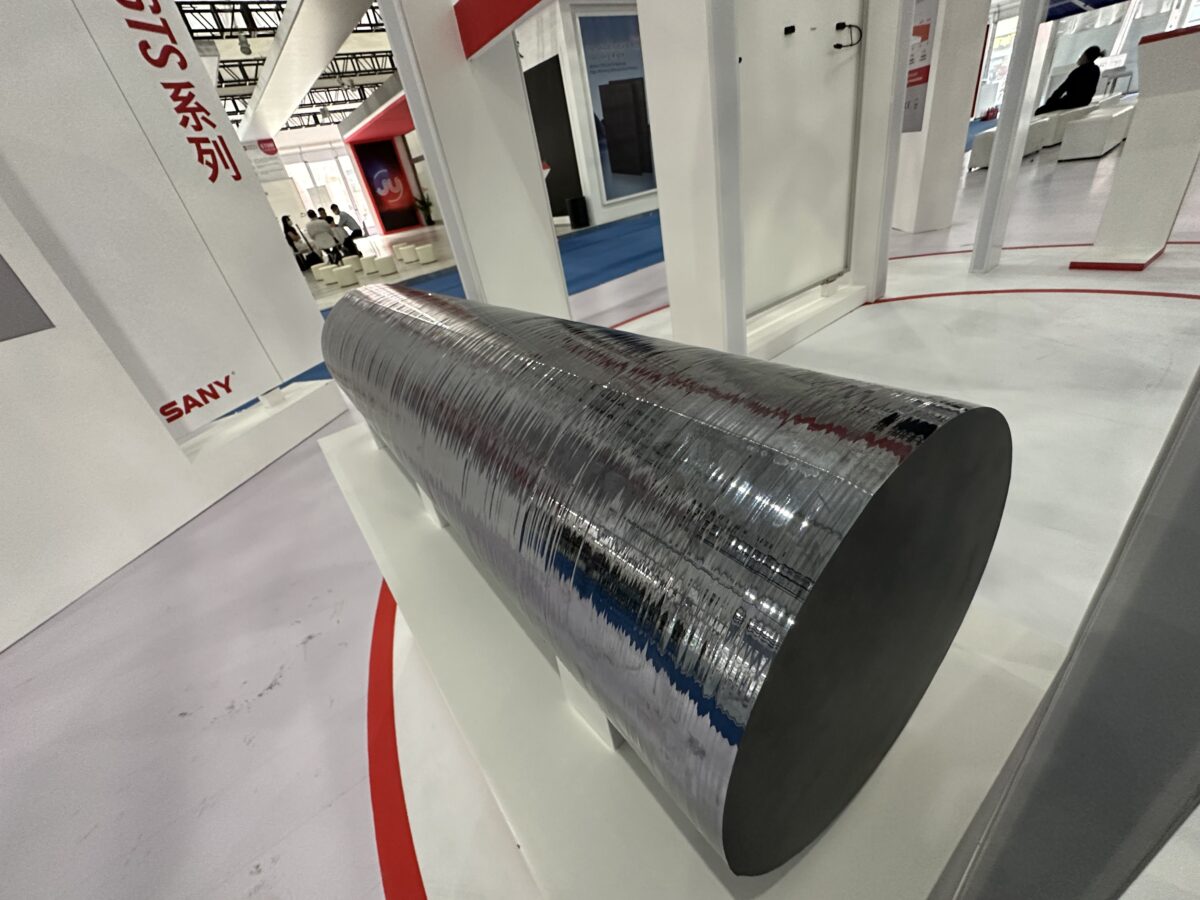

Another economic driver is advanced technology leading to larger, more efficient turbines that capture more wind. General Electric’s Paris-based unit GE Renewable Energy made a splash in July by introducing the Haliade-X 12 MW. Standing nearly 850 feet tall, with three rotors each spanning more than 720 feet, a single Haliade-X can power up to 16,000 homes.

“We knew that size mattered and capacity mattered, and we’re winning in both categories,” said John Lavelle, president and CEO of GE Renewable Energy’s offshore business. He said that the 12-MW colossus churns out 40% more power than any other turbine in the U.S. industry. GE had a leading U.S. market share of 41.4% at the end of 2018, per the American Wind Energy Association, followed by Danish wind giant Vestas (24.2%) and Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy (19.7%).

H/O GE Renewable Energy Haliade-X wind turbine

H/O GE Renewable Energy Haliade-X wind turbine Northeast states hold the most offshore wind potential. In New England there are four times as many proposals than those for natural gas-fired power plants, according to ISO England, a not-for-profit regional transmission organization. A 2017 report from the DOE’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimated that by 2027, New England could reach 144 GW of offshore wind capacity, with Maine and Massachusetts leading the way at 65 GW and 55 GW, respectively.

Massachusetts has come a long way since the debacle known as Cape Wind, a proposal dating back to 2001 to erect 130 turbines in Nantucket Sound, within eyeshot of Cape Cod, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. The project was ultimately scuttled in 2017 following a series of legal and financial setbacks and “not-in-my-backyard” protests from wealthy homeowners.

First utility-scale project suffers setback

Lessons learned from that bitter experience have sweetened prospects for several current projects in the Bay State being developed by Vineyard Wind, a partnership of Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and Avangrid Renewables, based in New Bedford, Massachusetts. First in the queue is so-called Vineyard Wind 1, situated more than 15 miles offshore. The developer had planned to flip the switch on the nation’s first utility-scale offshore wind farm in 2022, using an array of 84 9.5 MW Siemens turbines to electrify at least 400,000 customers.

But in August the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, the agency that leases and approves the sites, slammed the brakes on the $2.8 billion project. BOEM said it wants new studies that account for the “cumulative impacts” of future offshore wind projects proposed in the area.

Despite the setback, Erich Stephens, Vineyard Wind’s chief development officer, described the BOEM decision as a sign of just how much potential offshore wind energy offers.

“BOEM realizes they underestimated the rate of build-out of the U.S. offshore wind industry and had to go back and look at that,” he said, adding that there is no revised timeline.

On Dec. 5, Connecticut officials chose Vineyard Wind’s adjacent 804-MW Park City project as the winner of its first offshore wind solicitation. In June the state passed a law requiring 2,000 MW from offshore wind by 2030.

Scheduled to go online in 2025, Park City is expected to provide 14% of Connecticut’s entire energy needs. “It also advances a major step toward Gov. [Ned] Lamont’s goal of 100% zero-carbon electricity supply by 2040,” said Katie Dykes, commissioner of the state’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection.

Another decisive element in picking Vineyard Wind over two other bidders was its commitment to spend or invest nearly $890 million in Bridgeport, the state’s largest city and one of its most depressed. That includes building an 18-acre waterfront property, known as Barnum Landing, as a staging and preassembly site, and establishing an operations and maintenance facility, creating as many as 100 permanent jobs.

Last year Connecticut awarded two smaller offshore wind projects to Revolution Wind, a 600-MW joint venture between Orsted and Eversource, a regional energy company, with offshore turbines 15 miles south of Rhode Island. That project features a $93 million revitalization of New London’s State Pier. “We still have to get permitting for the project,” said Orsted’s Brostrom, which will take another two years. “Then construction will take another couple of years,” he said.

Floating wind power

Maine is moving forward with a relatively small, 12 -MW demonstration project, Aqua Ventus, scheduled to power about 9,000 homes in 2022. What distinguishes it, though, is a pair of 6-MW floating turbines designed by the Advanced Structures and Composites Center at the University of Maine.

Unlike conventional offshore wind turbines, which are affixed to pedestals moored on the ocean floor at depths up to about 200 feet, floating models are attached to cables anchored to the seabed. They are seen as a possible solution to building wind farms in deeper waters off Maine and California, a state that has pledged to be 100% carbon-free energy by 2045, yet has no offshore wind leases.

New York State passed a law in July mandating 9,000 MW of offshore wind by 2035. That same month, the state tagged Orsted and Eversource to construct the 880-MW Sunrise Wind project and Norway’s Equinor (formerly Statoil) to build Empire Wind, an 816-MW project. That’s in addition to Orsted’s South Fork Wind Farm, a partnership signed in 2017 with Long Island Power Authority.

Orsted is also developing the 1,100-MW Ocean Wind project 15 miles off the New Jersey coast from Atlantic City. In November, Gov. Phil Murphy announced the state is more than doubling its commitment, to 7,500 MW of offshore wind by 2035, meaning it would ultimately supply half of the Garden State’s electricity.

Although the future prospects are tremendous, right now there is only one offshore wind project actually under construction. Richmond-based Dominion Energy and Orsted are erecting two 6-MW turbines 27 miles off Virginia Beach, which are planned to go online sometime next year.

That is the first step toward a significantly larger, 2,600-MW adjacent project, set for completion in 2026, said Mark Mitchell, Dominion's vice president of generation construction. "We look at the two-turbine project as a front-row seat in the BOEM process, allowing us to work with them not only on permitting but also through construction and startup," he said.

BOEM is considering additional lease auctions for offshore sites, off the East Coast as far south as South Carolina, as well as California, Oregon and Hawaii, but there's no timetable. In the meantime, for the U.S. market to grow, "it needs predictable volume year in and out, certainty on schedules so we can plan [manufacturing] capacity and permits need to be issued in timely and predictable way," Lavelle said.