While this growth is translating to geothermal heated greenhouses in the Netherlands, a zero-emissions power plant in Italy and geothermal chocolate bars in the Philippines, it hasn’t meant much for Canada — despite the country’s substantial documented potential.

Geothermal energy comes from natural heat in the earth’s crust. Steam from hot spots near volcanic ranges, such as those in B.C., can be used to spin turbines to generate electricity, while warm water from cooler areas can be used as direct energy to heat homes, melt snow or grow food in greenhouses, like the Icelanders do.

The form of renewable energy, which provides uninterrupted baseload energy as opposed to intermittent alternatives such as wind and solar that rely on the weather, seems an obvious choice for many provinces and territories looking to increase sources of electricity while also decreasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Thus far, Canada is the only country on the Ring of Fire, a tectonic zone where the earth’s heat is abundant, that doesn’t have a single commercial geothermal power plant in operation.

But there have been positive developments — from a small geothermal power plant in Saskatchewan to an aquaponics startup in the Yukon — that may be signalling a long-awaited change in tide.

Saskatchewan’s DEEP geothermal project poised to be Canada’s first

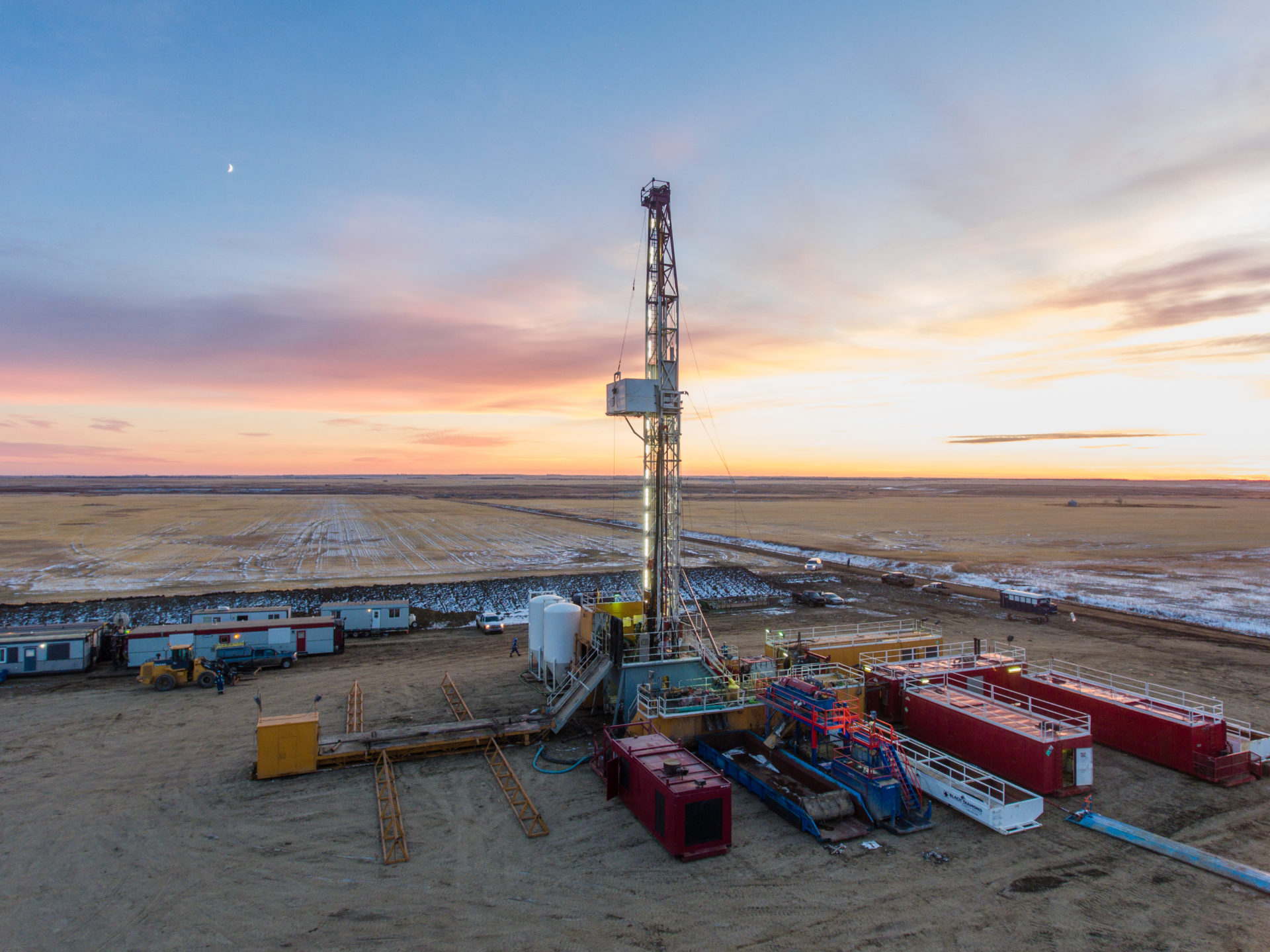

Advocates and supporters of geothermal energy across the country are watching construction of the DEEP project — Canada’s first geothermal power facility in the southern Prairies — with hopeful anticipation.

Located in southern Saskatchewan near the U.S. border, the DEEP project requires a well drilled down 3,500 metres and will generate approximately five megawatts of power from heat in the Williston Basin hot sedimentary aquifer.

The company estimates hundreds of megawatts of power could be developed in this basin with the drilling of additional wells.

“The DEEP project has stirred up a lot of excitement, people are asking questions that weren’t necessarily being asked before,” says Zach Harmer, policy director at the Canadian Geothermal Energy Association (CanGEA).

And the questions are important, because it’s a push-pull narrative between government policy and the public’s appetite for demanding change. “If you have the public on your side, chances are that politicians will want to be there,” he says.

And the DEEP project needed that political support. Initial exploratory work and feasibility studies cost the company $8 million — a substantial investment that was made worthwhile when the province’s utility provider SaskPower announced a power purchase agreement with the company that guaranteed a set price for the plant’s energy.

Jumping on the opportunity, the federal government announced $25.6 million in funding for the DEEP project earlier this year.

The project will power 5,000 homes a year while offsetting about 40,000 tonnes of carbon emissions, the equivalent of taking about 8,000 cars off the road, according to SaskPower. Wastewater from the project may also provide its own offshoot opportunity.

“There’s a huge business case for our wastewater,” DEEP CEO Marcia previously told The Narwhal.

“The water that comes out of the plant is still 65 degrees Celsius, so it’s extremely hot still. We’ve done some modelling on what we can do with that: as it turns out, from just one of our plants, we could heat a 45-acre [18-hectare] greenhouse.”

Marcia has also previously suggested that heat could help grow a variety of products, including legal marijuana.

The company announced it successfully drilled its first well — the deepest in the province’s history — in December.

Beyond its position as Canada’s first geothermal plant, the story of the DEEP project in Saskatchewan holds promise for another reason: its heat resource was originally mapped by oil and gas developers.

Leveraging Canada’s oil and gas data for geothermal

Canada first expressed interest in geothermal during the energy crisis of the 1970s.

Steve Grasby, a geoscientist with the Geological Survey of Canada, who worked on mapping Canada’s geothermal potential between 1975 and 1985, said most of the data we have about the resource stems from that original research.

“It’s fairly simple to determine how windy or sunny a place is,” Grasby told The Narwhal, “but much harder to know what the temperature of the rocks are [four kilometres underground] and do they have enough fluid to produce to surface.”

Refining the target zones through more passive methods, or “desktop studies” as he calls them, is helping to reduce the uncertainty of investing in active exploration.

Continued research and observation over the years have added layers of information to help pinpoint locations, but in comparison to research on other renewable energy sources Grasby said “geothermal is certainly behind,” and drilling is still the only way to be 100 per cent sure.

A deep well to get the essential data for geothermal costs millions, Grasby says. That’s a huge barrier, but one that can be eliminated when looking for geothermal where oil and gas activity has already taken place.

Wellhead data from the hundreds of thousands of wells drilled across B.C., Alberta and Saskatchewan includes temperature readings and has proven useful for estimating geothermal potential.

The Canadian Geothermal Association, for example, has identified more than 60,000 wells with bottom temperatures of more than 60 degrees Celsius. Of those wells, 7,702 have temperatures above 90 degrees, enough for heat exchange systems that can power refrigeration, and 500 showed temperatures above 120 degrees — hot enough for power generation.

As Alberta figures out what to do with its growing roster of unused wells, these legacy temperature readings provide the provincial regulator and energy companies with much needed information to determine where geothermal potential might underlie pre-existing oil and gas infrastructure.

That helps eliminate expensive risk, making geothermal projects much more attractive. This was the case for the town of Hinton, where some of these hotter wells are located. Last year the town received $1.2 million in federal and provincial funding to conduct a feasibility study of using geothermal for municipal heat and possibly electricity.

“In the renewable energy industry, we don’t have the privilege to have a well turn out to not be in the right area. It can be the make or break for a project,” CanGEA’s Harmer said.

This is also why getting government support and funding for “capacity-building projects” (shouldering some of the burden in drilling exploration so a community has enough funds to actually develop a power facility) is key.

Policy and tax incentives take shape, but hurdles remain

For many years, companies drilling for oil and gas across Canada were unable to drill for hot water. The permitting structure just wasn’t in place.

As far as policy goes, British Columbia and Saskatchewan are “at the forefront in Canada,” Harmer says; they’re the only provinces in Canada to have a formal framework that enables developers to drill explicitly for geothermal.

And it was just in 2017 that the federal government even acknowledged the existence of geothermal energy as a potential recipient of tax breaks and flow-through shares to help attract investment.

But even with a more lucrative tax structure, obstacles remain.

Geothermal energy is expensive, for starters, and requires a lot of capital investment up front. As a reliable, low-emission energy source with a small physical footprint, the gains of geothermal come over time, but perhaps not quickly enough to satisfy short-term political cycles.

More difficult, though, is a lack of appetite for energy from provincial utilities.

This, in part, accounts for an absence of geothermal power generation in B.C., where the resource is among the most promising in the country.

Geothermal “has not been competitive with other renewable resources because of its cost and exploration risk,” a spokesperson from the province’s ministry of energy, mines and petroleum resources told The Narwhal.

The ministry’s website touts the benefits of harnessing geothermal as “a source of clean, renewable energy with a small environmental footprint,” but is not expected to purchase electricity from alternative energy projects until after 2030, because of the construction of the Site C dam, which will add 1,100 megawatts of power to the provincial grid.

“Beyond 2030, additional conservation measures and geothermal, wind, solar and other clean, renewable resources can supply the electricity we need to support low-carbon electrification and achieve our climate targets,” the spokesperson said.

The Site C dam is expected to oversupply electricity to B.C.’s grid, pushing out wind and solar producers, while flooding 107 kilometres of the Peace River and its tributaries and displacing local residents who currently live in the dam’s flood zone.

This hasn’t stopped all geothermal activity in B.C., however. The town of Valemount is forging ahead with plans for a geothermal ecovillage that won’t rely on feeding power to the provincial grid and will instead generate power and direct heat for local businesses, including a brewery, greenhouses and a European-inspired spa.

Valemount’s geothermal project has survived despite a lack of support from the provincial utility, BC Hydro, which has put additional pressure on the local community partners and Borealis, the company spearheading the project, to stoke investor interest.

Borealis is using creative methods, such as aerial drone surveys, to keep exploratory drilling costs down.

Geothermal takes long-term vision

Those initial investments in drilling and building have long-term gains that will pay off financially, Harmer said, adding geothermal requires “an aged look at energy pricing.”

“If you look at the straight dollar per megawatt for geothermal energy, it’s expensive, but if you look at a levelized cost, then it is very comparable, even competitive with other forms of energy.”

But forging ahead with geothermal power may depend on the public demanding it, Harmer said. That also means getting a better sense of the role geothermal can play in areas other than energy production. Recently an agriculture company in the Yukon integrated direct geothermal heat from a local hot spring into its plans for an aquaponics greenhouse and tourist attraction.

“We need to see it as a viable solution.”