Although many new solar materials are being investigated, silicon remains by far the photovoltaic industry's favorite. "Monocrystalline silicon remains the material of choice in the PV industry due to its low cost, nontoxicity, excellent reliability, good efficiency and maturity of the manufacturing process," says Nazek El-Atab, a postdoctoral researcher in the labs of Muhammad Mustafa Hussain.

One drawback of silicon, for certain applications, is its rigidity, unlike some thin film solar cells. However, these flexible cells either consist of low-cost, low-efficiency organic materials or more efficient but very expensive inorganic materials. Hussain and his team have now taken a significant step toward overcoming this limitation by developing low-cost, high-efficiency, silicon-based stretchy solar cells.

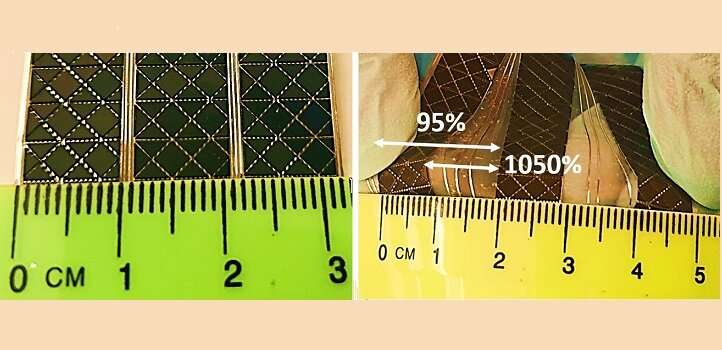

The key step was to take a commercially available rigid silicon panel and coat the back of the panel with a highly stretchable, inexpensive, biocompatible elastomer called ecoflex. The team then used a laser to cut the rigid cell into multiple silicon islands, which were held together by the elastomer backing. Each silicon island remained electrically connected to its neighbors via interdigitated back contacts that ran the length of the flexible solar cell.

The team initially made rectangle-shaped silicon islands, which could be stretched to around 54 percent, Hussain says. "Beyond this value, the strain of stretching led to diagonal cracks within the brittle silicon islands," he says. The team tried different designs to push the stretchability further, mindful that each slice of silicon they removed reduced the area available for light capture. The team tried a diamond pattern before settling on triangles. "Using the triangular pattern, we achieve world record stretchability and efficiency," Hussain says.

The team plans to incorporate the stretchy silicon solar material to power a multisensory artificial skin developed by Hussain's lab. Making solar panels that stretch with even greater flexibility is also a target. "The demonstrated solar cells can be mainly stretched in one direction—parallel to the interdigitated back contacts grid," Hussain says. "We are working to improve the multidirectional stretching capability."