Ayers Rock Resort at the village of Yulara near Uluru will be a world-leading test site for the technology.CREDIT:ALAMY

Ayers Rock Resort at the village of Yulara near Uluru will be a world-leading test site for the technology.CREDIT:ALAMY

Running a luxury resort in the middle of a desert is no easy task. Grass must be kept green and sweaty tourists cooled. There are shuttle buses to power, buffets to cook, phones to charge. The lights must stay on at the souvenir shop.

Until recently, the Ayers Rock Resort near Uluru relied mostly on natural gas, brought in by truck, to keep things running. Solar panels were installed a few years ago and the buses use diesel. But now there is a new plan to power the place: limitless, zero-emissions hydrogen.

The release this week of a Council of Australian Governments consultation paper on a national hydrogen strategy was another signal that finally, hydrogen's day may have arrived.

Adding to the momentum, the International Energy Agency last month declared 2019 a critical year for hydrogen, saying the resource could be poised to "fulfil its longstanding potential as a clean energy solution".

But the strong case for hydrogen has long been known. The question now is will the buzz translate into a real-world energy revolution? Or will high costs, political complacency and industry skittishness mean another false start?

Scientists say zero-emissions hydrogen is among the emerging technologies that must be scaled up if the planet is to have any hope of avoiding the most catastrophic climate change effects.

So what is hydrogen? Colourless and odourless, it's the most abundant chemical element in the universe and fills stars and gas planets like Jupiter and Saturn. On Earth it is not freely available as a gas but is bound into many common substances including water and fossil fuels.

To break these bonds and produce hydrogen requires various technologies, and an energy source to power it all.

Hydrogen can be turned into electricity or methane to power homes and industry, and can power cars, trucks, ships and planes. It can be transported through pipelines as a gas or on ships as a liquid. It is also an energy "carrier", meaning it can be generated by renewable energy, stored then deployed as needed.

Australia's chief scientist Alan Finkel is a vocal cheerleader for hydrogen's potential. He is devising the national hydrogen strategy, to be delivered later this year, and hopes that one day Australia will develop hydrogen into a clean, everyday energy source to replace fossil fuels.

"I believe the time for hydrogen has come. You only need to look at our recent national election to see that," he says, in reference to policies from both parties to develop a domestic hydrogen industry.

Finkel likes to use the phrase "shipping sunshine" when describing how electricity from Australian solar plants could produce clean hydrogen for export. By 2030, he says Australia could have a hydrogen export industry worth $1.7 billion, providing 2800 jobs.

Finkel's strategy is not finished. But he already knows that turning hydrogen from a golden opportunity into a real-world energy transformation means producing, storing and moving it at colossal scale.

"This is not something that can happen overnight, it is a journey to be navigated with patience, innovation and determination," he says. "We will need to build out gradually, learning and re-calibrating along the way."

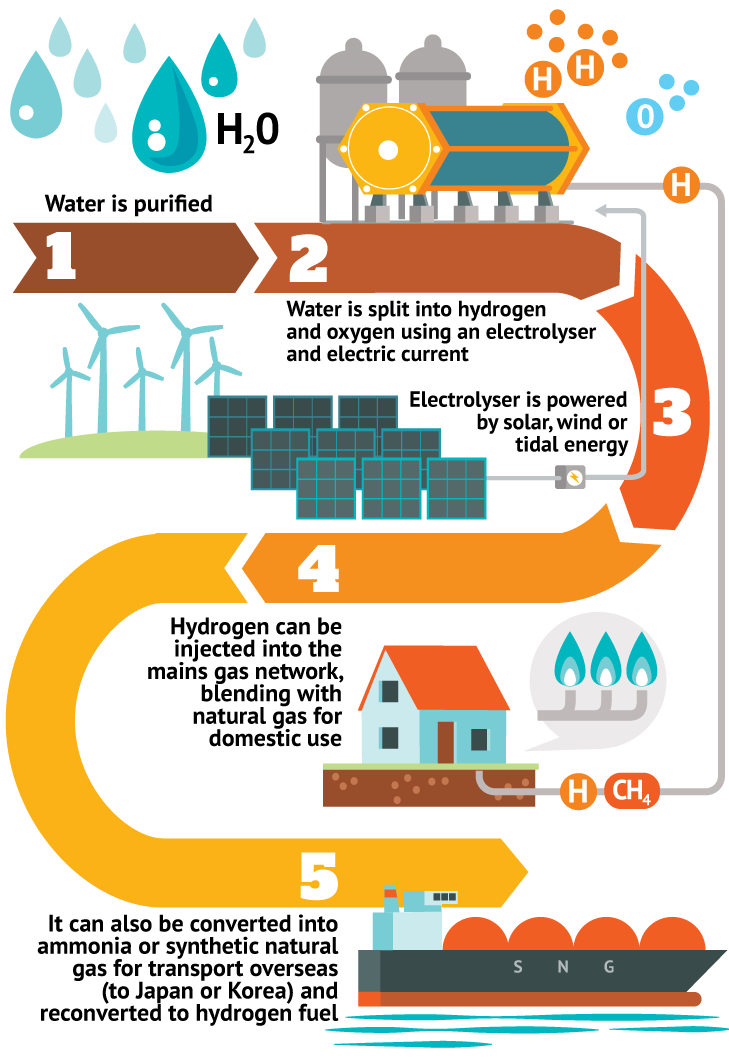

Clean, or zero-emissions hydrogen can be produced in two ways. Electricity, such as that generated by solar or wind, can be used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen; it can also be produced from coal or methane using technology that captures and stores carbon.

If the Northern Territory government gets its way, the Ayers Rock Resort at the township of Yulara will be a world-leading test site for the technology.

In a submission to the national hydrogen strategy, the government said the resort's high reliance on fossil fuels could be displaced using hydrogen generated from solar "to create a hydrogen-centric town".

A diesel tourist bus fleet and gas-fired cooking and heating could become hydrogen-powered, as could the resort's water supply which relies on gas-fired bore pumps.

Graphic: Matt Davidson. Source: ARENA

Graphic: Matt Davidson. Source: ARENA

"The marketing power of this location can be leveraged to turn a solar-hydrogen solution into a worldwide headline," the territory government says.

Finkel says Australia is well placed to produce and export hydrogen at scale due to its abundance of wind, sun and fossil fuels and proximity to Asian markets that are soon expected to become major hydrogen importers. They include Japan, which imports about 90 per cent of its energy needs. By next year Japan is aiming to power 40,000 electric vehicles with hydrogen fuel cells, to coincide with the Tokyo Olympics where hydrogen will reportedly power the athletes' village and light the Olympic cauldron.

Neither Japan nor South Korea – another potentially lucrative export market - have the means to produce hydrogen efficiently themselves.

An International Energy Agency analysis released last month found that in 2030 it would be cheaper for Japan to import Australian hydrogen than to produce it onshore – even taking into account transport costs.

But the agency cautioned that the cheapest source of hydrogen would still be substantially more expensive than natural gas, and "further cost reductions would be needed" to boost its competitiveness.

Any bid by Australia to be a world leader in hydrogen production would be challenged by countries including Norway, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, which are also racing to develop the technology.

The federal government has so far invested about $100 million in hydrogen research and development. According to a CSIRO report last year, 15 hydrogen projects are under way in every Australian jurisdiction except Tasmania and the Northern Territory.

In Victoria's Latrobe Valley, struggling with the coal industry decline, the Hydrogen Energy Supply Chain project is billed as a world-first pilot to demonstrate that hydrogen can be safely and efficiently produced from brown coal then transported as a liquid to Japan. Technology to capture and store carbon produced by the project is also being developed.

In Western Australia, the Asian Renewable Energy Hub aims to generate at least 11,000 megawatts of renewable energy, most of which will enable hydrogen production.

While Australia's hydrogen strategy is expected to be export-driven, it will also have benefits at home. Hydrogen is already used in applications such as oil refining and fertiliser manufacturing. But long-haul trucks could be powered by hydrogen fuel cells and natural gas could be replaced with hydrogen to heat homes and cook food.

To adopt the parlance of the Morrison government, hydrogen also promises to ensure renewable energy provides "fair dinkum" reliable power. Electricity from wind and solar is intermittent – it cannot be produced on demand if the sun isn't shining and the wind isn't blowing. But when renewables are producing electricity, hydrogen can store the energy for days, weeks or even months – much like batteries - then release it when and where it's needed.

But all this could be academic. The promise of hydrogen is not disputed. Waves of enthusiasm for the technology have come and gone before – following the 1973 global oil crisis and again in the 1990s when the public cottoned on to the climate change threat. The question is whether the barriers to producing hydrogen at a fossil-fuel scale can be broken through.

A hydrogen road-map produced by the CSIRO last year found that the technologies in Australia are relatively mature, and it is time for Australia to turn hydrogen into a profitable commercial industry. The report said that "while government assistance is needed to kick-start the industry, it can become economically sustainable thereafter".

The hurdles are many. Australia does not yet have the infrastructure needed to scale up, and hydrogen is still expensive to produce compared with other fuels.

Hydrogen produced from coal and gas emits greenhouse gas pollution, unless the carbon can be captured and stored. But that technology, known by the acronym CCS, is far from being proven at commercial scale in Australia.

The Australian Conservation Foundation, in a submission to the national hydrogen strategy, said given Australia's exceptional renewable resources there was "no reason to divert further resources into unproven CCS to shore up further fossil fuel use".

Producing hydrogen from renewable energy is not without potential environmental problems, however. For every 1 kilogram of hydrogen produced through electrolysis – splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen – nine litres of water is needed. Little is known about how a full-throttle hydrogen export industry would affect scarce water resources in Australia, the driest continent on Earth.

One participant in a University of Queensland study last year put the conundrum like this: "You are saying renewables with water [can produce hydrogen]. Do we currently have a surplus of water in Australia? You ask people in NSW, the farmers, they are fighting over water. If they went down that path, where is that extra water going to come from?"

Clean hydrogen proponents say the industry should only be developed in areas of adequate water supply, and say desalination plants or water recycling facilities could produce water for electrolysis.

Remove from shortlistHydrogen it also is highly flammable. As the CSIRO has noted, consumers today are happy to drive cars filled with petrol – also a highly flammable fuel – but they may consider hydrogen-powered cars to be more dangerous. Critical public support for a hydrogen industry could be garnered through demonstration projects, community engagement and appropriate regulations and safety standards, CSIRO says.

The International Energy Agency has identified the key actions governments and industry around the world should take to help hydrogen reach its potential.

Hydrogen should be included in the energy strategies of nations, regions and cities. Policies should be implemented to create markets for clean hydrogen and encourage investment, which would bring costs down.

Companies wanting to deploy new hydrogen applications are often taking on big investment risk, and should be supported with tools such as public loans and guarantees. Governments should continue to invest in research and development, and unnecessary regulatory barriers should be removed. International co-operation is required and countries should make the most of existing infrastructure such as industrial ports and gas pipelines.

The transition to hydrogen, if it occurs, will not come quickly. It will take big-picture thinking and forbearance. True believers say hydrogen could, in coming decades, rival the scale of Australia's liquefied natural gas sector. Last year Australia became the world's biggest exporter of LNG – 30 years after the first shipments left our shores.

Chief Scientist Alan Finkel knows full well the challenges. But he remains optimistic. "When I think about the world in 2050, I see freeways lined with refuelling stations, carrying battery electric cars, hydrogen electric cars, buses and trucks, thousands of square kilometres of solar [panels] and hydrogen powered cargo ships criss-crossing the globe," he says.

"It's glorious and getting there is feasible, but it won't be easy."