Since 2016, as an informal leader of the 13-strong non-OPEC group, Russia has been instrumental in the pricing of oil as Saudi Arabia, leading producer in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Now, both find themselves at odds as to how to respond to the global economic crisis caused by the fall in petroleum demand resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak.

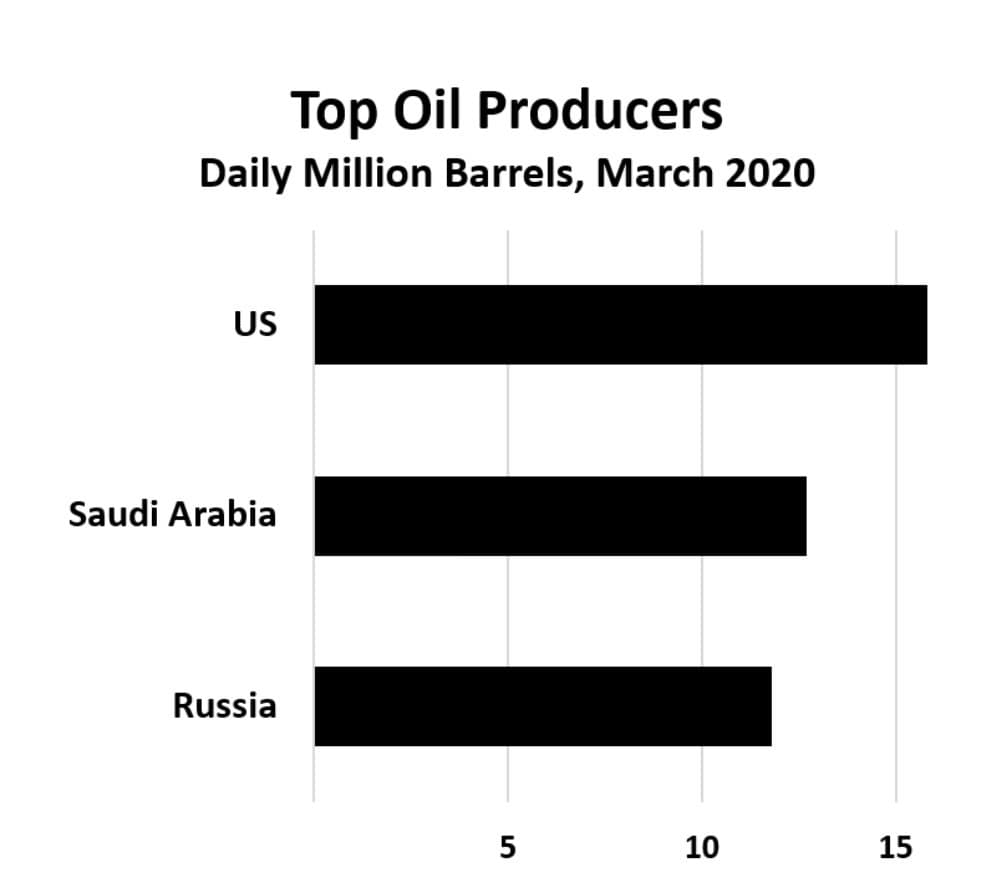

The Saudis insisted on overall cuts to be shared by OPEC and non-OPEC with a 2:1 ratio. Russia saw no need for any cuts because, in its view, earlier OPEC and non-OPEC curtailments had allowed the US shale oil industry to fill the gap. With the sharp fall in oil prices, many small-scale shale oil drillers in the United States will go bankrupt as happened in late 2015 when the Saudis Starting in 2014, aided by high oil prices and technical advances, shale oil drillers boosted US crude oil production, accounting for a third of the onshore output. This raised US oil production from 5.7 million barrels per day in 2011 to a record 17.94 million bpd in 2018, outstripping Russia and Saudi Arabia – transforming the United States into an oil-exporting country after President Barack Obama lifted the 40-year-old crude-oil export ban in December 2015, following a congressional vote to that effect.

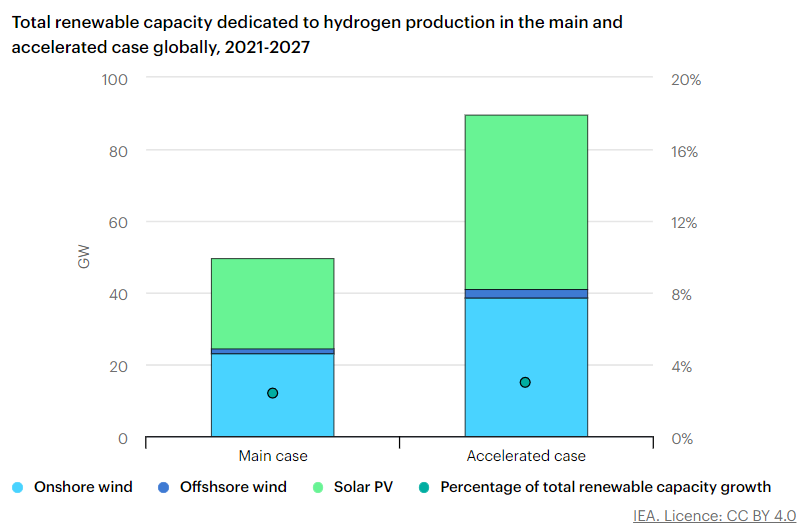

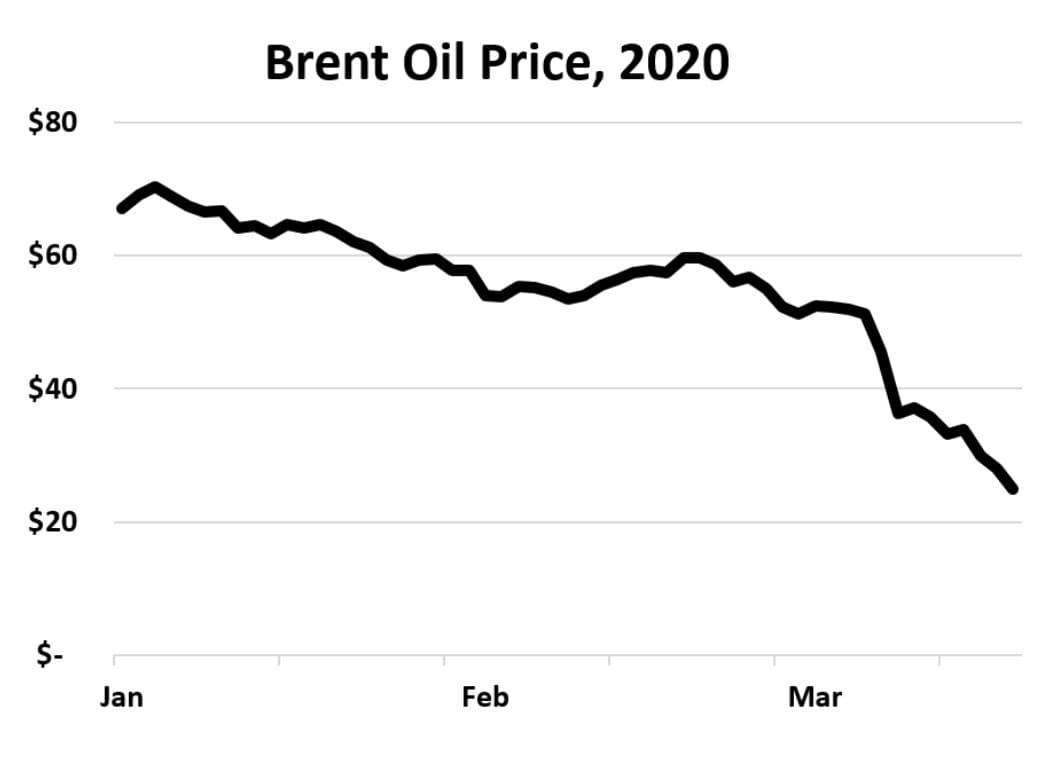

Frenzy: Russia refused to go along with a Saudi plan to reduce oil productions, both nations opened taps and prices soared (Source: Oil and Gas 360, Bloomberg)

Frenzy: Russia refused to go along with a Saudi plan to reduce oil productions, both nations opened taps and prices soared (Source: Oil and Gas 360, Bloomberg)

By banding together such non-OPEC oil producers as Azerbaijan, Bahrain and Bolivia as well as Kazakhstan and Mexico, Russia broke new ground and sealed its leadership role in December 2016 when OPEC and non-OPEC groups agreed to production cuts to remove a global oil glut rising rapidly since early 2016.

King Salman bin Abdulaziz, after his enthronement in January 2015, decided to thaw relations with the Kremlin. He sent his favorite son, Mohammad, 29, deputy premier and defense minister, along with his foreign and oil ministers to Russia’s International Economic Forum in St. Petersburg in June. During his meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Prince Mohammad bin Salman discussed Saudi investments in Russia, then under US and European Union economic sanctions. After the Kremlin’s September military intervention in the Syrian Civil War siding with President Bashar al Assad, the prince rushed to Sochi for a meeting with Putin and reassurance that Russia was not planning to forge a military alliance with Iran.

The return of Iran to the oil market in January 2016, following its denuclearization deal with major powers, and US entry into the oil-export market created a glut. Prices plummeted to $27 a barrel from the peak of $115 in mid-2014, before stabilizing around $50 a barrel. That led Prince Salman and Putin to meet on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Hangzhou, China, on 5 September and agree to cooperate in world oil markets by limiting output, clearing the global glut and raising prices.

As a result OPEC and non-OPEC groups agreed to their first joint oil output cut in December 2016: OPEC’s share was 1.2 million bpd and non-OPEC’s 558,000 bpd. By slashing 500,000 bpd, Saudi Arabia reduced production by 4.5 percent from 10.56 million bpd, and Russia curtailed its output by 300,000 bpd. Immediately, the Brent crude price jumped 10 percent to nearly $52 a barrel, and US West Texas Intermediate, crude, WTI, rose 9 percent to $49.50.

The launching of a mutually beneficial strategy in oil exports prepared the ground for widening Riyadh-Moscow links. King Salman became the first reigning Saudi monarch to visit Moscow in October 2017. The two sides inked 15 cooperation agreements covering oil, military affairs, including a $3 billion arms deal and even space exploration. Putin offered to sell versatile S-400 anti-aircraft missiles to the monarch who demurred. Coinciding with the royal visit, the Council of Saudi Chambers organized a networking meeting in Moscow for Saudi and Russian business leaders. As newly appointed Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammad attended the inaugural ceremony of the World Cup tournament in Moscow in June 2018 as Putin’s guest.

After the devastating drone and missile attacks on Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities in September 2019, Putin repeated his offer of S-400 missiles to Riyadh during a 16 September news conference after a meeting on Syria with Turkish and Iranian counterparts: “We are ready to help Saudi Arabia protect their people,” he said. “They need to make clever decisions, as Iran did by buying our S-300, as Mr. Erdo?an did by deciding to buy the most advanced S-400 air defense systems.” Facing stiff US opposition to accepting Putin’s offer, Salman continued to dither.

Nonetheless, during his state visit to Riyadh in October, Putin brought most of his cabinet and around a hundred top Russian business executives. He and his royal host oversaw the signing of 21 bilateral agreements involving billions of dollars of investment contracts in such sectors as aerospace, culture, health and advanced technology. During a meeting with the Saudi crown prince, Putin mentioned that the Saudi Public Investment Fund allocated $10 billion for joint foreign direct investment projects in Russia.

On the oil front, Russia found its market share dwindling in the face of increasing US oil exports and discounts that Saudi Aramco had started providing buyers to increase market share. The 2019 cuts agreed to by OPEC and non-OPEC countries were due to expire 31 March, with a new agreement required to limit supply. Between 1 January and early March, oil prices declined by 20 percent to $46 a barrel after the Northern Hemisphere’s warmest weather on record and the unexpected outbreak of the COVID-19 disease that originated in China.

OPEC developed a plan to slash output by 1 million bpd with Russia-led non-OPEC countries cutting 500,000 bpd. Putin rejected any cuts because, he argued, earlier curtailments had allowed US shale-oil producers to increase market share to the extent that the United States had become a leading petroleum exporter.

Angered by this rejection, Crown Prince Mohammad ordered Saudi Aramco to give deep discounts on its oil after 1 April. Saudi Aramco also announced that it would raise output to an unprecedented 12.3 million bpd from the current 9.8 million bpd. Putin came up with an increase of 300,000 bpd for Russia. By the end of the trading on 9 March, the benchmarks Brent crude and the American WTI each collapsed by about 25 percent to $34.36 a barrel and $31.13 a barrel, respectively. Global markets went into a tailspin. The US Federal Reserve injected billions into the financial system since 12 March and the market has been volatile since, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average down more than 30 percent for the year.

Double whammy: COVID-19 reduced oil demand, and failure of OPEC and non-OPEC groups to cut production levels halved prices (Source: MacroTrends)

Double whammy: COVID-19 reduced oil demand, and failure of OPEC and non-OPEC groups to cut production levels halved prices (Source: MacroTrends)

In the Putin-Salman standoff, analysts ponder which man will blink first. With a fiscal break-even petroleum price of $42.50 per barrel, Russia’s economy is more diversified than its Saudi counterpart, with a strong defense industry, the exports of which are second only to America’s. For Saudi Arabia, the fiscal break-even oil price is $85 per barrel, reports the International Monetary Fund. However, Riyadh’s foreign and gold reserves at $496.8 billion in September 2019 were higher than Moscow’s $419.6 billion.

In Russia, fossil fuels and energy exports account for 64 percent of total exports. Its oil and gas sector covers 46 percent of total government expenditure and contributes about 30 percent to GDP. In Saudi Arabia, the petroleum sector accounts for roughly 85 percent of the kingdom’s revenue, 90 percent of export earnings and 42 percent of GDP.

Following US and EU sanctions in 2014, Russia suffered a recession that ended after 2017 with an upsurge in oil prides. Since then, the economy has stabilized, but its recent spat with Riyadh caused the ruble’s value to depreciate by 10 percent.

Earlier, pressured by cheap Saudi oil in 2015, the US shale oil industry reduced its breakeven point from $65 to $46 a barrel. With oil now selling for $30 a barrel, the industry faces a renewed challenge. If this continues, history will repeat itself with many small, independent US drillers filing for bankruptcy because of their failure to repay loans from banks, which had accepted untapped oil reserves as collateral. That development will undoubtedly please the Kremlin.