Toyota chairman Takeshi Uchiyamada said in 2016: ‘We’re not about to give up on hydrogen electric fuel-cell technology at all.’ (Photo: Supplie

Toyota chairman Takeshi Uchiyamada said in 2016: ‘We’re not about to give up on hydrogen electric fuel-cell technology at all.’ (Photo: Supplie Effervescent multi-entrepreneur Elon Musk famously described hydrogen-powered fuel-cell cars as ‘mind-bogglingly stupid’. The 200,000-plus people employed in SA’s platinum mines better hope he is wrong, because if he is right, the platinum industry is destined to go the same way as SA’s gold industry.

Effervescent multi-entrepreneur Elon Musk famously described hydrogen-powered fuel-cell cars as ‘mind-bogglingly stupid’. The 200,000-plus people employed in SA’s platinum mines better hope he is wrong, because if he is right, the platinum industry is destined to go the same way as SA’s gold industry.

The perilous future of the platinum industry depends largely on the development of the hydrogen fuel-cell car, and the omens look pretty bad –but not as bad as popularly believed. This battle is not done yet; not by a long shot.

In 2016, Elon Musk, the conceiver and CEO of electric vehicle company Tesla, was asked about hydrogen cars. Not one to hold back, Musk went on a famous rant, saying there were multiple rebuttals to the idea of a hydrogen-powered car, which would become increasingly clear over time.

It’s very difficult to make hydrogen and store it for use in a car, he said. Electrolysis (the process which uses platinum to create the electricity) is an extremely inefficient energy production system, roughly half as efficient as just using battery power. The hydrogen atom is pernicious and hard to control. If you do get a leak, it’s invisible and extremely dangerous.

And so he went on. Overall, the technology was “extremely silly”, he said.

What Musk meant by the “pernicious” nature of hydrogen is that, in its natural state, hydrogen is a gas. In order to control it and use it effectively, it has to be massively pressurised or cooled to produce a liquid. That adds huge costs to the infrastructure and makes manufacturing products that use it technically tricky. The hydrogen atom is so small, it can, in its gas form, escape through steel.

Musk found surprising support in 2016 when Yoshikazu Tanaka, the chief engineer of the one hydrogen car out there at the time, Toyota’s Mirai, said “Elon Musk is right — it’s better to charge the electric car directly by plugging in”.

And yet. And yet.

Hydrogen is one of the most available chemicals in the universe. It’s everywhere. Powering something with hydrogen generates steam; it’s fabulously environmentally attractive. The air that comes out of the engine is cleaner than the air that goes in. The cars literally scrub the atmosphere.

This is partly why are now three large car companies committed to producing hydrogen cars. Even Tanaka said hydrogen remains a viable alternative to gasoline, and Toyota chairman Takeshi Uchiyamada said in 2016, “We’re not about to give up on hydrogen electric fuel-cell technology at all.”

But, even the most ardent hydrogen supporters would acknowledge that it’s been uphill from there. Between 2016 and now, the electric car has been the major talking point in the car industry, and car companies are rushing out new EVs (electric vehicles) at a furious rate. Musk’s Tesla is now churning out cars, and the Tesla Model 3 outsold the equivalent models of BMW, Mercedes and Audi in Europe in June 2019. Yes, in Europe.

There are now about 5,000 Mirai cars on the roads, sold over the past four years. That’s the same number of Model 3s that Tesla is producing every week.

In addition to the lack of hydrogen fuelling stations, there are two other problems. The base price of a Mirai is around $60,000, about the same as Hyundai’s Nexo Blue. A Tesla Model 3 costs a little more than half that, illustrating the comparative construction complexity.

And the cost of filling up with hydrogen is roughly three times as much as it would cost to fill up what is now derisively called an “ICE” (internal combustion engine) car in the US. (In Europe, for various reasons, the costs are about the same). Fuelling is so expensive, car companies are covering the fuel costs for hydrogen cars for three years.

So on the face of it, Musk is totally right. We are stuffed. But, it turns out, it’s not quite as simple as that.

To get a different perspective, I spoke to Andrew Hinkly, the CEO of AP Ventures, which is the only investment fund in the world that focuses on downstream uses of platinum group metals (PGMs). AP Ventures, unsurprisingly, emerged out of AngloPlatinum and is also supported by the Public Investment Corporation.

AP Ventures began last year and has invested in nine high-growth start-up companies in the US and Europe. The first fund is fully invested, and the second fund raised $90-million.

I asked Hinkly if Musk was stupid to call hydrogen fuel cell vehicles stupid, hoping he would answer with an emphatic “yes”. Sadly, he went for a more nuanced response.

The opportunities for hydrogen are not necessarily in opposition to EVs but in association with them, he said. “You wouldn’t use a corkscrew to open a bottle of beer”, he added, and went on to provide a host of examples.

In an industrial setting, the time it takes to recharge a EV battery is a problem. So if you have three eight-hour shifts moving packages around in a factory, hydrogen-powered machines that you can refuel in a few minutes make more sense. This is why Amazon is replacing its battery forklifts with hydrogen-powered machines.

Batteries also tend to diminish in power as they get to the end of their lifespan, which might be tolerable in a car, but not in a factory where optimal power is required 100% of the time.

Long-range, heavy-use vehicles might be better suited to hydrogen power, which is why Anglo Platinum has undertaken to convert its mining vehicles to fuel-cell technology.

More than that, some of the problems of hydrogen storage are being solved. One of AP Ventures’ investments, a German company called Hydrogenious, has won all kinds of German prizes for developing a technology that allows hydrogen to be transported in a liquid form without using compression and cooling. This is big, and explains why the number of hydrogen fuel stations in Germany is likely to double in the next couple of years.

Other companies are experimenting with the efficient creation of hydrogen, which could be used as a way of storing excess energy production, including as it happens, the excess daytime or summer production of solar power.

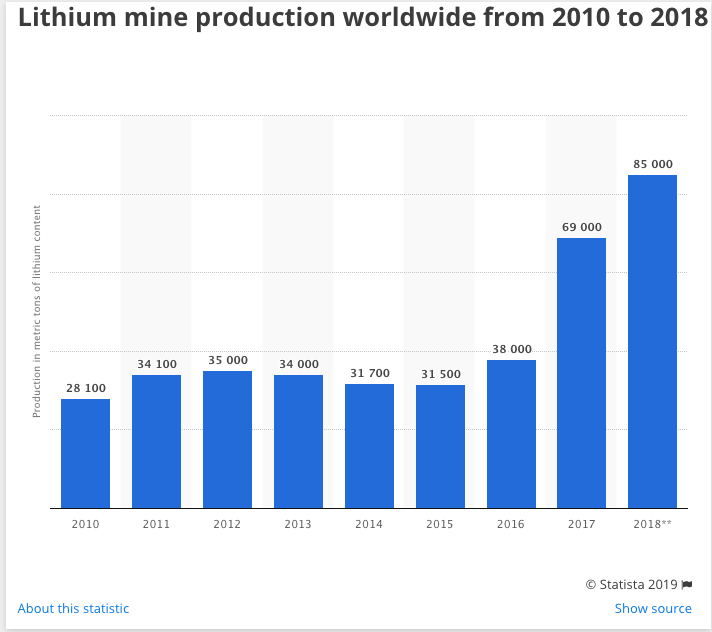

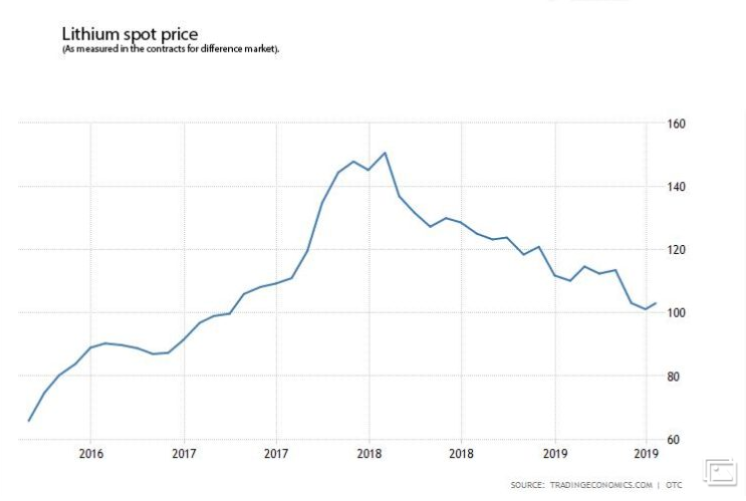

Musk himself inadvertently let slip in 2018 he was concerned about lithium production, saying Tesla might go into the mining business.

Hinkly says the platinum industry infrastructure is already established, and the product itself, platinum, is fully recyclable. “There isn’t a new extractive requirement; we are just repurposing minerals that are already being mined.”.

I asked Hinkly what would be the tipping point that would signify hydrogen fuel cells were getting real traction. He said it was unlikely to be a crescendo effect, that there would be more adoption where it makes sense commercially.

Eariler in 2019, the first double-decker hydrogen buses were put into operation; Germany is now committed to 80 hydrogen fuel stations, which means you won’t be more than 300km (about half a fuel-cell car’s range) from a fuelling point on a major route. The first Chinese exports of fuel-cell cars are about to start, and more cargo vehicles, ferries, and trucks are in the planning stages.

Auditing firm KPMG does an influential annual survey of the car industry, and in 2017, 78% of 1,000-odd auto executives said they believe hydrogen fuel cells have a better long-term future than electric cars. The 2019 version estimated that the market in 2040 would be evenly split between EVs, ICE cars, hybrids and fuel-cell cars.

“It will be piece by piece,” Hinkly said. The SA mining industry better hope he is right.