Like Iran, we have a refinery problem. Is the United States really energy independent? Is Iran? As the two nations inch toward confrontation, the complexity of those questions is worth considering.

A pump jack operates in the Permian Basin oil and natural gas production area near Midland, Texas, August 23, 2018

A pump jack operates in the Permian Basin oil and natural gas production area near Midland, Texas, August 23, 2018

Iran, like many petro-powers, had long maintained a one-horse economy based on extraction. Oil and petroleum-related products account for almost all of its exports — take those away, and you’re down to fruits and nuts.

Iran has an awesome abundance of oil but for many years did relatively little to develop its refining capacity, without which crude oil is not very useful. That is partly the result of Iran’s having a feckless and corrupt government and partly the result of sanctions that made building new refineries very difficult. When the expansion of the Persian Gulf Star Refinery at Bandar Abbas came on line in 2018, that doubled Iran’s domestic refining capacity and greatly reduced the country’s gasoline imports. The Iranian regime has declared the country liberated from the need to import gasoline, but it currently disallows most exports, and the CEO of the state refining company only a week ago decried the “prohibitive consumption” of gasoline — which is now at a record level — suggesting that the domestic supply is not quite as abundant as the ayatollahs would like.

Iran had been rationing gasoline as recently as 2007. The Iran sanctions act of 2010 poked Iran in the tender spot of its gasoline imports (about 40 percent of Iranian gasoline consumption at the time), with provisions that would prohibit most gasoline and other vehicle fuel sales (aviation gas, etc.) exceeding $5 million in any one-year period along with equipment or services that would enable the domestic production or import of gasoline. One of the criticisms of President Obama’s decision to lift sanctions on Iran in 2016 was that doing so might give Iran an opening to build out its refining capacity, taking away a critical vulnerability.

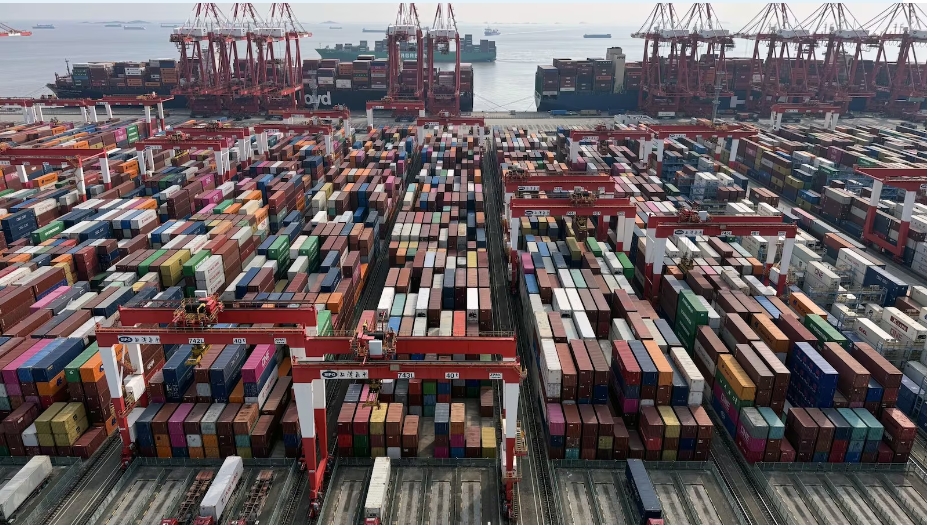

While Iran has been expanding its refining capacity, the U.S. oil industry hasn’t exactly been following suit. U.S. refining capacity is up by about 1 million barrels a day over where it was a decade ago — not nothing, but not a real dramatic line on the graph, either.

And that creates a potential vulnerability for the United States.

President Trump has a natural affection for the oil business. (That is not what we mean by crude and unrefined, Mr. President!) But in spite of all the chest-thumping you hear from certain politicians about how the country has become “energy independent,” that is not really true. The United States imports billions of barrels of crude a year, about a third of it from OPEC. At the same time, the United States exports a substantial quantity of the stuff. That’s because most of the refineries in the United States were built when the country was still obliged to rely very heavily on imported oil, and so most of them are optimized to handle the “heavy sour” stuff from abroad rather than the “light sweet” stuff from Texas. It is not the case that a barrel of oil is a barrel of oil is a barrel of oil. “Every single molecule from here on out has to be exported,” Cynthia Walker of Houston-based Occidental Petroleum told the Texas Tribune.

If all cross-border trade in oil and petroleum products were halted tomorrow, Iran would have some big problems. But so would the United States, which very likely would end up sitting on a surplus of oil but suffering shortages of gasoline and other fuels. The Trump administration deserves credit for encouraging domestic oil production and for pursuing regulatory reforms to help get government out of the way, but the reelection-minded president also is dead set to pucker up and kiss the collective buttocks of the Republican heartland’s politically influential corn farmers and their ethanol bonanza. In fact, the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers association is suing the administration over an ethanol expansion that oil producers say exceeds the president’s authority to order.

When Hurricane Harvey walloped Houston in 2017, gasoline pumps were dry in Dallas and points north, hundreds of miles away. The Colonial pipeline, which carries gasoline and aviation fuel from Houston to New York City, was shut down, as were several refineries feeding it.

Having oil in the ground isn’t enough. Drilling holes isn’t enough. The process of turning crude oil into useful products and getting those products to the people who need them is complicated. They know that in Tehran. They know that in Houston. Let’s hope they know that in Washington.